In a recent clinical study, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, have pioneered a novel gene therapy that holds the promise of a healthier life for 10 young children who were born without a functional immune system and lacked the ability to fight infection. The findings are published in the December 22, 2022 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine in a paper titled “Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Artemis-Deficient SCID”.

Artemis-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (ART-SCID) is a very rare genetic disorder that is usually treated with a bone marrow transplant from a healthy donor (preferably a matched brother or sister). This new gene therapy allows scientists to treat newly diagnosed infants with their own cells—by adding healthy copies of the Artemis gene to bone marrow stem cells collected from sick infants and then infusing the corrected bone marrow stem cells back into their bodies, hopefully avoiding many of the short- and long-term complications of standard treatment, including death.

Dr. Mort Cowan, corresponding author of the paper and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, said the children in this clinical trial were all under 5 years old, living at home with their families, attending day care and preschool, playing outside and leading normal lives.

Cowan has previously treated more than 30 children with ART-SCID with standard bone marrow transplants, and Cowan said that their disease course had been much better than typical treatments, which has never seen in other children.

Genetic correction has been used previously to treat patients with other genetic forms of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), but its use in ART-SCID is significant because these patients typically respond poorly to standard bone marrow transplants. Complications may include bone marrow graft rejection, graft-versus-host disease (the donor’s T cells attack the recipient’s tissue), chronic infection leading to organ damage, growth retardation, and premature death.

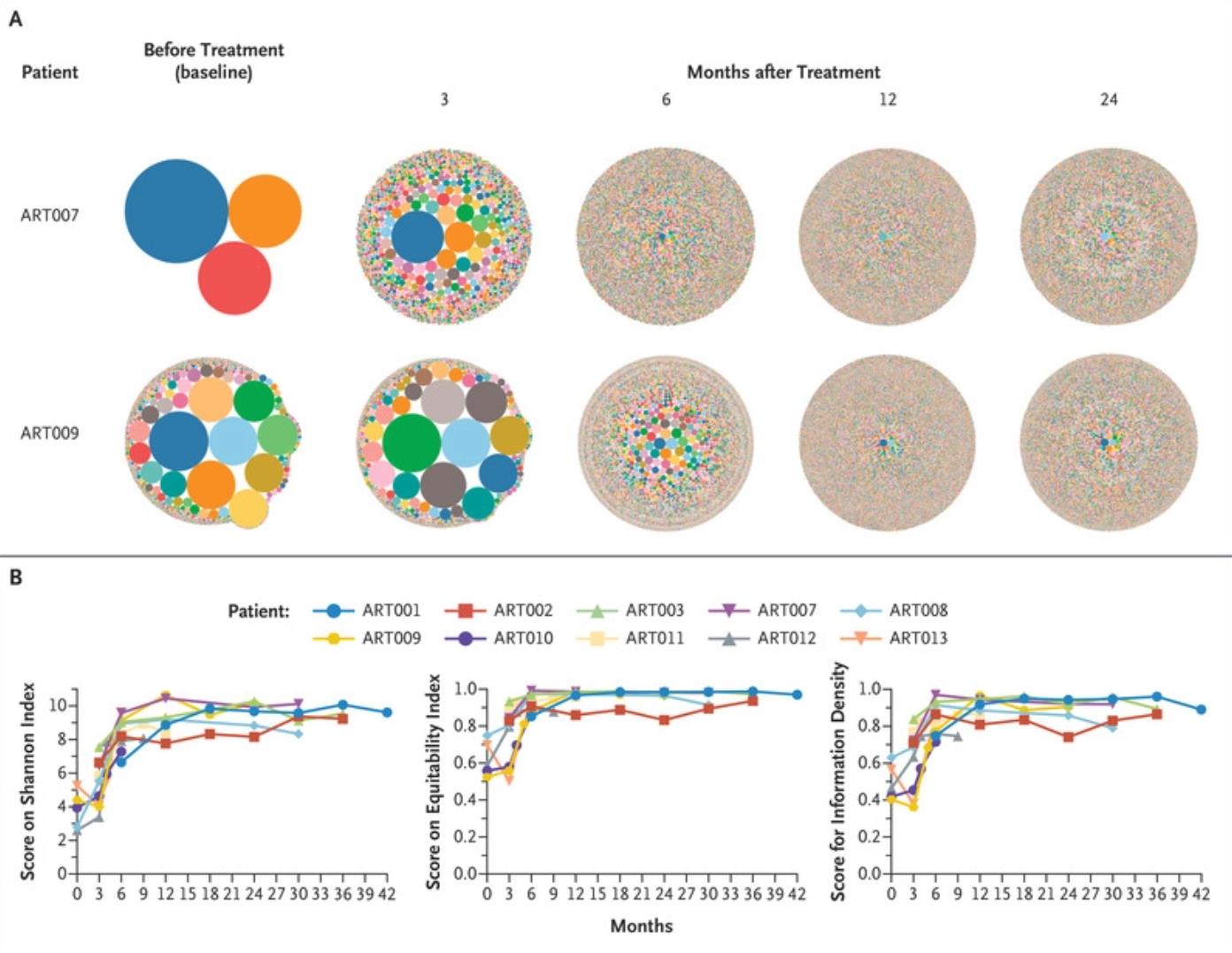

The first results of this phase I/II clinical trial involved the safe infusion of genetically corrected bone marrow stem cells that differentiate into white blood cells within 42 days of infusion. These authors speculated that when patients used their own cells, they needed less chemotherapy to prepare for the blood transfusion; therefore, only 25% of the full dose of busulfan, a chemotherapy drug, needed to be given. The second outcome was T-cell reconstitution at 12 months, which is a measure of the strength of the immune system.

All 10 children were safely infused with their own genetically corrected bone marrow stem cells, which produced genetically corrected peripheral blood cells within 42 days. All 10 children grew their own T and B cells by 12 weeks, and 4 of the 9 children (excluding one who received a second treatment) achieved complete T-cell immune reconstitution by 12 months. 4 of the 9 children also achieved complete B-cell immunity by 24 months, allowing them to discontinue immunoglobulin replacement and receive standard childhood vaccinations. 3 other children, followed for less than 24 months, had good prospects for B-cell development compared with the outcomes of children who had previously received donor bone marrow transplants.

One child required a second infusion of genetically corrected bone marrow stem cells due to persistent cytomegalovirus infection prior to gene therapy, but is now infection-free and has good T- and B-cell immunity. Dr. Jennifer Puck, co-author of the paper and professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that all outcomes are better than those of children with ART-SCID who previously received donor bone marrow transplants.

In this clinical trial, giving the children full T-cell immunity achieves outstanding results. It usually takes longer for B-cell recovery, but it also appears that the children have a far better chance of B-cell reconstitution than with conventional bone marrow transplantation. The use of less chemotherapy is also a big win, minimizing the harmful side effects of a full dose of leucovorin in smaller infants.

Cowan added that better B-cell immunity may be able to help avoid problems such as chronic lung disease that often develop later in childhood of children with ART-SCID who receive standard bone marrow transplants.

The research shows that a novel gene therapy holds great promise in this very rare disease, and the technology can also be applied to other diseases.

Reference

1. Cowan, Morton J., et al. “Lentiviral gene therapy for artemis-deficient SCID.” New England Journal of Medicine 387.25 (2022): 2344-2355.