In a new study, researchers from the University of Utah, Rockefeller University, and Pennsylvania State University determined how CHMP3 variants (RetroCHMP3) discovered in mice and monkeys interfere with the replication of enveloped viruses such as HIV and Ebola. This variant causes alterations in the protein encoded by the CHMP3 gene, disrupting the ability of enveloped viruses to release from infected cells and preventing follow-up infection of other cells. This discovery may eventually lead to the development of new medical interventions to prevent enveloped virus infection.

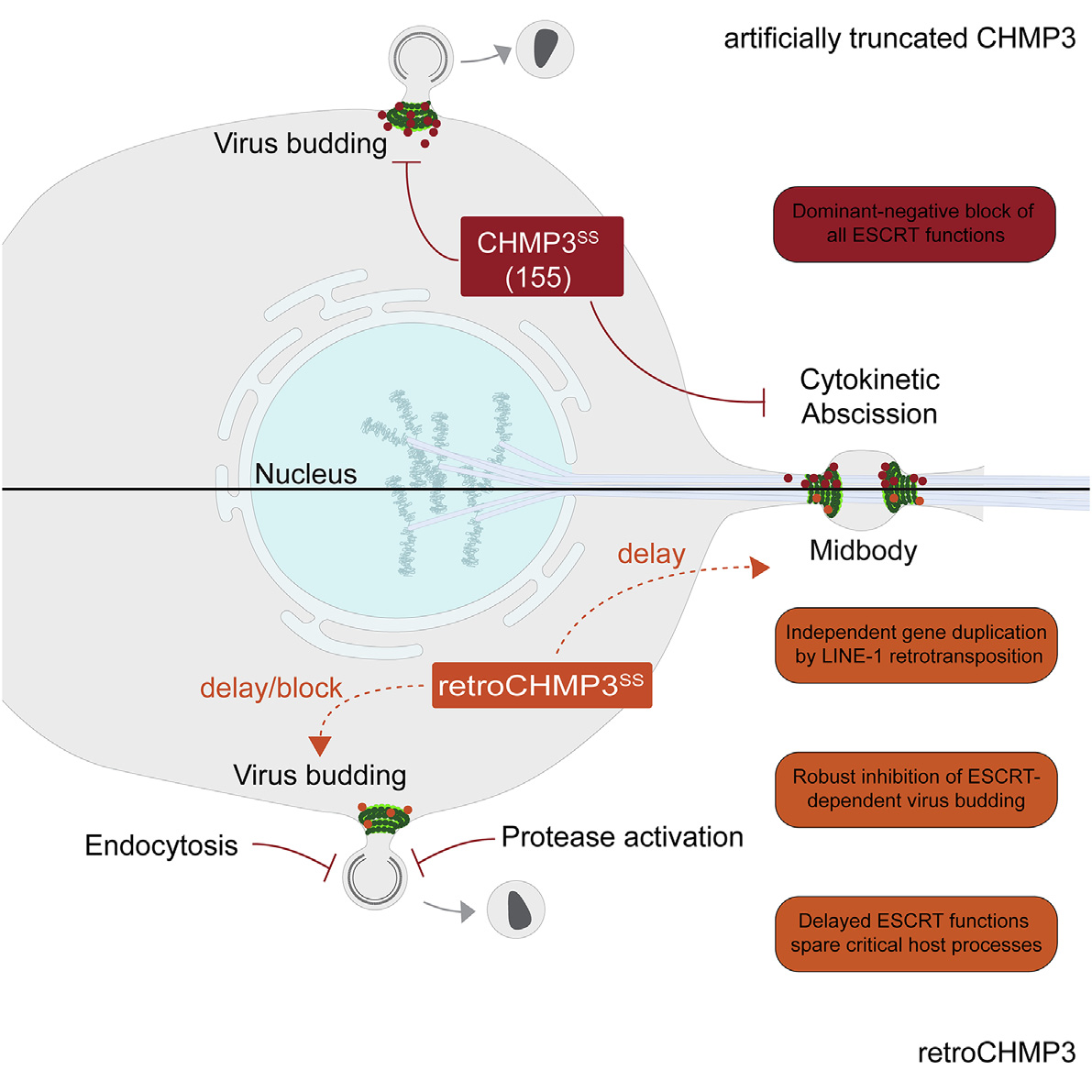

RetroCHMP3 blocks budding of enveloped viruses without blocking cytokinesis. (Cell)

Usually, some viruses wrap themselves in the envelope and then exit by sprouting from the host cell. RetroCHMP3 delays this process so that the virus cannot escape from the host cell using the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) pathway. “This was an unexpected discovery,” Dr. Nels Elde said. “We were surprised that slowing down our cell biology just a little bit throws virus replication off its game.”

RetroCHMP3 originates from a repetitive copy of CHMP3 (multivesicular body protein 3) gene. Although some monkeys, mice, and other animals have retroCHMP3 or other variants, humans have only primitive CHMP3 that plays a key role in maintaining cell membrane integrity, intercellular signal transduction, and cell division in humans and other organisms. HIV and some other viruses hijack the ESCRT pathway to sprout from the cell membrane and infect other cells. Based on the findings, Dr. Nels Elde and his colleagues speculated that RetroCHMP3 found in monkeys and mice prevents this from happening, which may be used to prevent viruses such as HIV and other viral diseases.

On this basis, Dr. Nels Elde and his colleagues began to explore whether the variants of CHMP3 could be used as a new antiviral drug. Using genetic tools, they induced human cells to express the retroCHMP3 found in squirrel monkeys, and then infected the cells with HIV and found it difficult for the virus to sprout from the cells. At the same time, such situation does not damage the metabolic signals or related cellular functions that can lead to cell death. From an evolutionary point of view, Dr. Nels Elde believes this represents a new type of immunity that can be developed quickly.

Scientists previously thought that the ESCRT pathway, which is always used by enveloped viruses such as HIV and Ebola to sprout from host cells and infect new cells, was an Achilles’ heel. The discovery of RetroCHMP3 changed that. The findings raise the possibility that interventions which slow this process may not be important to host cells, but provide a new direction for antiretroviral drug development.