Tissue Model Introduction

Tissue models function as biological constructs created to reproduce both the structure and function of natural human or animal tissues in laboratory-controlled conditions. Tissue models replicate critical physiological features unlike conventional 2D cell cultures which cannot recreate complex cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, cellular heterogeneity and architectural complexity. Animal models deliver systemic context but face challenges due to species-specific differences and ethical concerns as well as high financial costs and extended experimental durations. Tissue models provide a human-focused and reproducible research platform which satisfies ethical standards and facilitates the principles of animal testing reduction known as "3Rs" (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement). These tissue models function as "mini-organs" which serve as functional units that replicate organ behavior to enable precise and predictive scientific investigations. immune response, Tissue models have found extensive applications in various fields such as tumor research, target analysis, and immuno-oncology drug discovery.

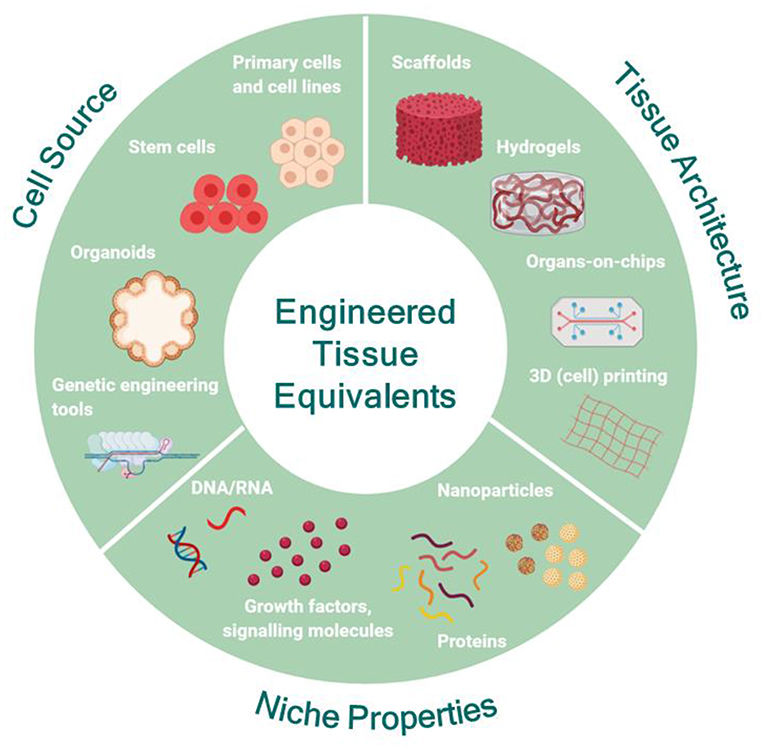

Figure 1 Engineering human tissue equivalents in vitro.1,3

Figure 1 Engineering human tissue equivalents in vitro.1,3

Types of Tissue Models

|

Tissue Model Type

|

Examples

|

Applications

|

|

Bone Tissue Models

|

3D scaffolds with osteogenic cells, bone-on-a-chip systems, ex vivo bone explants

|

Research focuses on bone diseases including osteoporosis and Paget's disease alongside bone regeneration processes and the evaluation of biomaterials for implants and screening drugs meant to prevent osteoporosis.

|

|

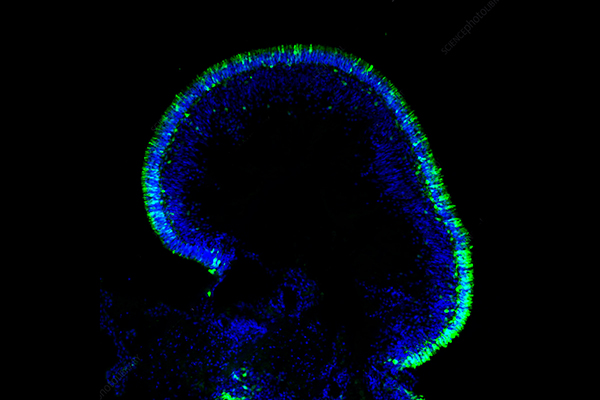

Nervous Tissue Models

|

Brain organoids, neural spheroids, microfluidic devices for axonal growth/BBB, precision-cut brain slices

|

The research focuses on modeling neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's through neurotoxicity testing and studying synaptic plasticity to advance drug development for neurological disorders.

|

|

Adipose Tissue Models

|

3D adipocyte cultures, co-culture with endothelial/immune cells

|

The research examines obesity and diabetes along with metabolic syndrome while assessing anti-obesity medications as well as compounds that influence lipid metabolism.

|

|

Skin Tissue Models

|

Full-thickness skin equivalents, reconstructed human epidermis (RHE), skin-on-a-chip systems

|

The scientific investigation includes cosmetic testing for irritation and sensitization along with wound healing research together with dermatology drug screening and UV radiation damage evaluation.

|

|

Liver Tissue Models

|

Hepatic spheroids, liver organoids, liver-on-a-chip devices

|

Research focuses on predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI) along with investigating liver diseases such as NAFLD and NASH and advancing personalized medicine.

|

|

Kidney Tissue Models

|

Kidney organoids (from iPSCs), glomerulus-on-a-chip, kidney tubule models

|

Research focuses on testing drugs for kidney toxicity potential alongside models of polycystic kidney disease and renal physiology studies.

|

|

Cardiac Tissue Models

|

Engineered heart tissues (EHTs), cardiac spheroids, heart-on-a-chip systems

|

Cardiotoxicity screening processes alongside modeling cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial infarction studies with development of regenerative therapies for heart failure.

|

|

Tumor Tissue Models

|

Tumor spheroids, patient-derived organoids (PDOs), tumor-on-a-chip models

|

Drug sensitivity testing for personalized oncology paired with tumor microenvironment research leads to the identification of novel therapeutic targets and anti-cancer drug evaluation.

|

|

Gastrointestinal (GI) Tissue Models

|

Gut-on-a-chip, intestinal organoids (enteroids/colonoids), co-culture models with immune cells/microbiota

|

Research activities include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) investigation, nutrient uptake assessment, drug permeability analysis and host-microbiome relationship studies.

|

|

Lung Tissue Models

|

Alveolus-on-a-chip, airway organoids, precision-cut lung slices

|

Research focuses on the pathophysiology of asthma alongside COPD and cystic fibrosis as well as viral infections (SARS-CoV-2) and inhalation toxicology processes.

|

Research Progress of Tissue Models

Tissue models represent an innovative field which consistently expands the scope of biological engineering and biomimicry. The development of more advanced and functional systems has achieved significant progress.

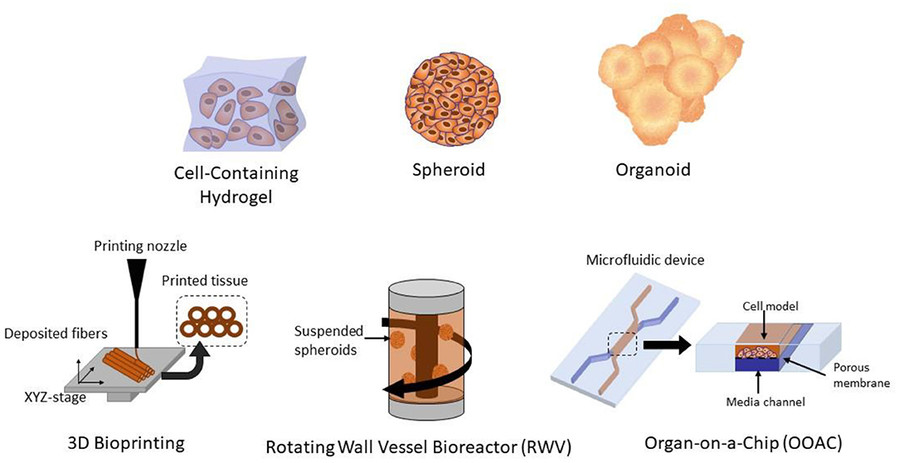

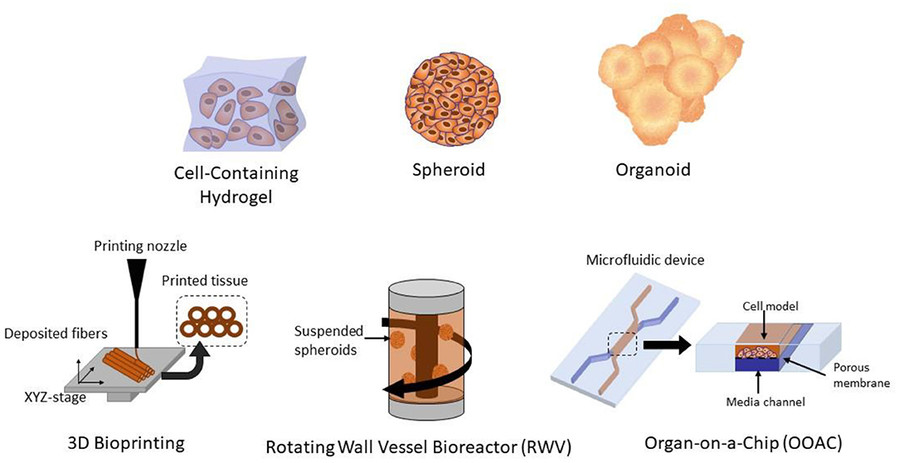

Figure 2 Different methods of 3D cell culture for tissue models.2,3

Figure 2 Different methods of 3D cell culture for tissue models.2,3

-

Organoids: Stem cells from embryonic, adult tissues or iPSCs develop into self-organizing 3D structures that function as mini-organs mimicking essential elements of true organ structure and operations. Recent advancements include:

-

Organ-on-a-Chip Technology: The design of these microfluidic devices enables them to mimic human organ physiology on chips through the implementation of mechanical forces along with fluid flow and diverse cell types positioned at tissue interfaces. Key progress includes:

-

Integration with AI and Machine Learning: Modern tissue modeling now frequently employs computational methods for the purpose of design and optimization as well as analysis. AI systems enable researchers to determine optimal culture conditions and analyze sophisticated imagery from tissue models while aiding in the development of new biomaterials and scaffold structures.

How to Make Tissue Models?

Developing advanced tissue models requires collaboration across multiple disciplines including cell biology along with materials science and engineering principles. The general workflow often includes:

01 Cell Isolation and Culture: Researchers begin by extracting cells from tissue samples or acquiring them from cell banks before placing them in a nutrient-rich medium to support growth and survival.

02 Scaffold Preparation (for 3D Models): The preparation of scaffolds for 3D models utilizes natural or synthetic materials like collagen and PLGA to provide cells with necessary structural support. 3D printing allows for the creation of exact scaffold shapes.

03 Cell Seeding and Differentiation: Subsequently researchers plant cells onto the scaffold while maintaining precise control of cell density. Cells can undergo differentiation into specific cell types through growth factor induction when necessary and scientists track this differentiation process through multiple analytical methods.

04 Tissue Maturation: Under controlled environmental conditions the model undergoes incubation which leads to cellular proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion enabling cells to form a mature tissue-like structure. Complex systems such as vascular networks require extra procedures during development.

What Tissue Forms the Model for Endochondral Ossification?

Hyaline cartilage serves as the primary model tissue in the process of endochondral ossification. The process of endochondral ossification begins when mesenchymal cells turn into chondrocytes that generate an extracellular matrix creating a hyaline cartilage model that resembles the future bone. The cartilage model experiences multiple transformations such as hypertrophy and calcification which precede its gradual conversion to bone tissue.

Examples of Bones Formed by Endochondral Ossification

-

Long bones (e.g., femur, tibia, humerus)

-

Short bones (e.g., carpals and tarsals, though with less defined growth plates)

-

Vertebrae and most bones of the axial skeleton

-

The base of the skull and parts of the pelvis

Key Difference from Intramembranous Ossification

|

Feature

|

Endochondral Ossification

|

Intramembranous Ossification

|

|

Initial tissue

|

Hyaline cartilage model

|

Mesenchymal (connective) tissue

|

|

Bone types

|

Long bones, base of skull, vertebrae

|

Flat bones (e.g., skull vault, clavicle)

|

|

Vascular invasion

|

Critical for cartilage replacement

|

Occurs during bone formation but less central

|

Ex vivo tissue models function as a crucial intermediary phase linking basic laboratory research to in vivo biological studies. Scientists use "ex vivo" to refer to the practice of conducting experiments on living tissues and organs which they have removed from organisms but maintain functional outside of the organism as this term comes from Latin where it means "outside the body." This method preserves the original tissue structure by maintaining detailed cell-cell connections and extracellular matrix constitution as well as multicellular complexity which is often lost in dissociated cell cultures.

|

Feature

|

Ex Vivo Tissue Model

|

In Vivo Model (Traditional)

|

|

Origin of Material

|

Tissues/organs extracted from a living organism.

|

Whole living organism.

|

|

Environment

|

A laboratory setting mimics natural conditions with minimal changes to study ex vivo tissue models through either 2D or 3D cultures or perfused organ systems.

|

Natural biological environment within the organism.

|

|

Complexity & Systemic Interactions

|

This model maintains tissue structure and cellular interactions but shows no inherent regulation from body systems unless these functions are deliberately preserved.

|

A living system exhibits full complexity through its complete physiological systems while also showing interactions between organs and systemic responses.

|

|

Experimental Control

|

The experimental environment provides comprehensive control over conditions within experiments as well as nutrient provision and stimulus application. Easier to isolate variables.

|

The inherent complexity of living systems restricts researchers' ability to control confounding variables.

|

|

Physiological Relevance (to humans)

|

The preservation of tissue structure makes this approach more suitable thanin vitro methods when working with human tissues. Less interspecies variability than animal in vivo.

|

Animal models provide essential insights into organismal responses but face limitations in direct translation because of their interspecies differences.

|

|

Ethical Considerations

|

The research produces lower results compared to in vivo studies because it utilizes removed tissues which minimizes ethical concerns about live animal testing and human participation.

|

Animal tests and human clinical studies face major ethical challenges which demand rigorous ethical review processes and oversight mechanisms.

|

|

Reproducibility

|

The results demonstrate effectiveness when tissue handling and culture conditions undergo proper standardization.

|

High variability in individual organisms regarding genetics and environment and diet factors creates significant challenges.

|

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Do tissue models accurately reflect the complexities of human physiological systems?

A: No in vitro model can fully replicate all human body systems but advanced tissue models provide substantially better physiological relevance than conventional methods. Tissue models become powerful research tools when they integrate human cells with proper biomaterials alongside dynamic culture conditions to replicate main features of human tissue function which aids drug response prediction and disease mechanism comprehension.

Q: Can tissue models replace animal testing entirely?

A: Tissue models serve as growing ethical alternatives that lessen animal testing needs but cannot yet substitute every in vivo research requirement. Animal models provide a comprehensive systemic environment that encompasses intricate immune and endocrine interactions. Tissue models excel in delivering precise human-relevant data for organ-specific toxicity and personalized drug efficacy which enhances animal study findings.

Q: What the benefit of 3D bioprinting in tissue models?

A: The unparalleled precision of 3D bioprinting enables exact control over cell and biomaterial placement to produce complex tissue constructs with defined architecture. Through this process researchers can build multi-cellular structures along with vascular networks and exact layering that replicates native tissues essential for developing functional and stable tissue models.

Overview of What Creative Biolabs Can Provide

Creative Biolabs pushes biomedical research forward through their full spectrum of innovative tissue model products and services. Research teams and pharma industry partners benefit from our cell biology and tissue engineering expertise along with biofabrication skills to overcome traditional research barriers and accelerate their research development processes.

Custom Models

Culture Products

Creative Biolabs is dedicated to providing high-quality, consistent, and physiologically relevant tissue models and associated services, empowering researchers worldwide to achieve groundbreaking scientific discoveries and accelerate the translation of research into clinical applications.

References

-

Moysidou C M, Barberio C, Owens R M. Advances in engineering human tissue models. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 2021, 8: 620962. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.620962

-

Lawko N, Plaskasovitis C, Stokes C, et al. 3D tissue models as an effective tool for studying viruses and vaccine development[J]. Frontiers in Materials, 2021, 8: 631373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.631373

-

Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

Research Model

Figure 1 Engineering human tissue equivalents in vitro.1,3

Figure 1 Engineering human tissue equivalents in vitro.1,3

Figure 2 Different methods of 3D cell culture for tissue models.2,3

Figure 2 Different methods of 3D cell culture for tissue models.2,3