Animal Model Serivce for Oncolytic Virus Study

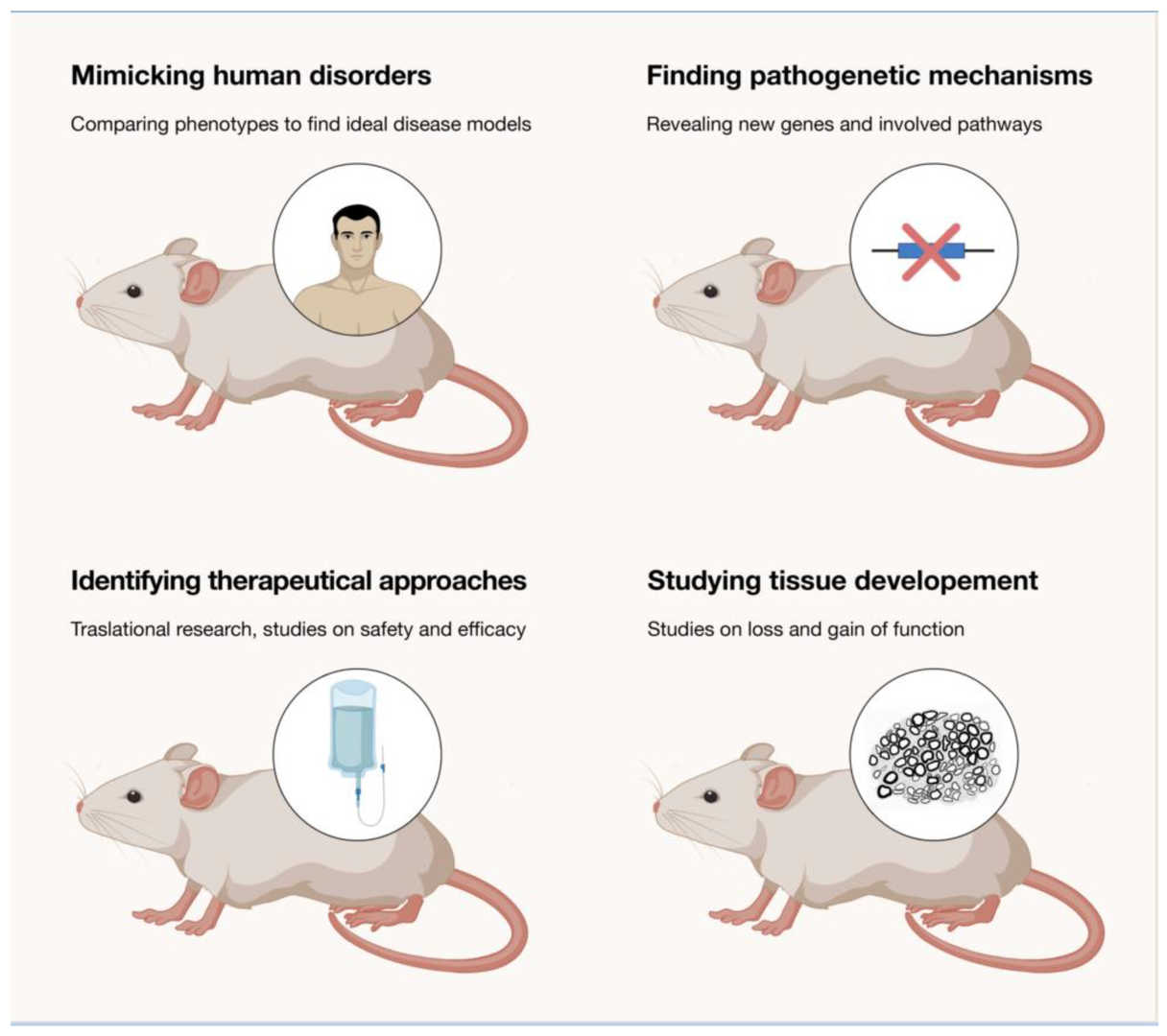

Animal models have significant advantages for in vivo preclinical studies of oncolytic viruses. It can simulate the physiological environment of the human body, and the tissues, organs, and cell types of animals such as mice and rats are similar to those of humans. It provides the survival and action space for oncolytic viruses similar to the human body and helps to study the replication, spread, and interaction of viruses with host cells in the body. Through long-term follow-up of animals, we can understand the long-term effect of oncolytic viruses, and we can also construct specific gene knockout or overexpression models to explore the mechanism of specific genes.

Mouse Model

Immunodeficient mice (e.g., nude, nod-scid, and NSG mice) and immunocompetent mice (e.g., C57BL/6, BALB/c) have distinct pros and cons in oncolytic virus research.

Immunodeficient mice, lacking mature immune cells, can accept xenogeneic tumor cells, enabling the study of oncolytic virus effects on human tumor cells without immune rejection. However, their incomplete immune systems limit immune-activation research.

Immunocompetent mice, with intact immune systems, are useful for creating syngeneic tumor models. These models reflect virus replication, spread, and immune-system interactions well, fitting for studying immune activation and tumor immune escape.

Rat Model

The relatively large size of rats offers advantages in surgical tumor implantation and virus injection procedures, rendering them a valuable complement to the mouse model. In oncolytic virus research, rats can be utilized to investigate the distribution and metabolism of the virus within larger-bodied animals, as well as its inhibitory impact on tumor growth. The commonly used rat models include the SD rat and the Wistar rat.

Fig.1 The use of rodents in oncolytic virus experiments.1,3

Fig.1 The use of rodents in oncolytic virus experiments.1,3

Nonhuman Primate Models

Non-human primates, such as macaques and cynomolgus monkeys, exhibit a high degree of similarity to humans in terms of genetics, physiology, and immunity. As a result, they can more accurately mimic the pharmacokinetics, toxicology, and immune responses of oncolytic viruses in humans.

Other Animal Models

- Rabbit models: Some organs and tissues of rabbits, such as the skin and eyes, closely resemble those of humans. In oncolytic virus research, rabbits can be used to establish cutaneous or ocular tumor models. These models help investigate the therapeutic efficacy and safety of oncolytic viruses at these specific sites, allowing for a better understanding of virus-tumor interactions.

- Dog model: Canine tumor diseases are similar to human tumors in natural progression and pathological features. Large-breed dogs are often predisposed to osteosarcoma. Using canine models in oncolytic virus research helps us better understand the clinical application of oncolytic viruses, as the biological similarities between canine and human tumors offer direct insights for human tumor treatment.

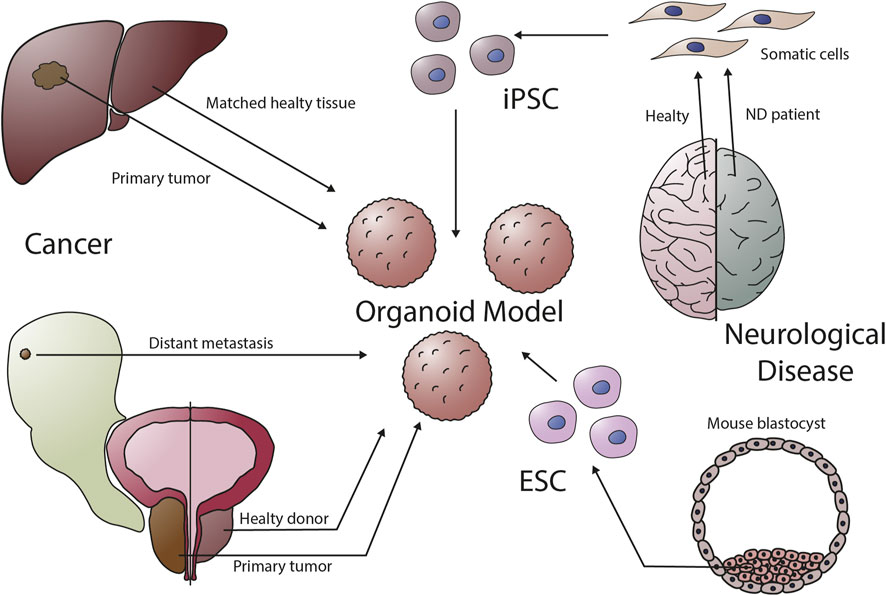

Organoids

Derived from in vitro culture human cells, organoids closely mimic human physiology and pathology. They accurately represent tumor development and the action mechanisms of oncolytic viruses, minimizing individual-difference interference and enhancing experimental repeatability. Comprising various cells within the tumor and its microenvironment, organoids enable in-depth exploration of virus-host interactions and immune mechanisms.

Fig.2 Organoids can be established from a variety of organs.2,3

Fig.2 Organoids can be established from a variety of organs.2,3

References

- Bosco, Luca, Yuri Matteo Falzone, and Stefano Carlo Previtali. "Animal models as a tool to design therapeutical strategies for CMT-like hereditary neuropathies." Brain Sciences 11.9 (2021): 1237.

- Lampart, Franziska L., Dagmar Iber, and Nikolaos Doumpas. "Organoids in high-throughput and high-content screenings." Frontiers in Chemical Engineering 5 (2023): 1120348.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.