Hepatocellular Carcinoma Specific Oncolytic Virotherapy Development Service

Introduction

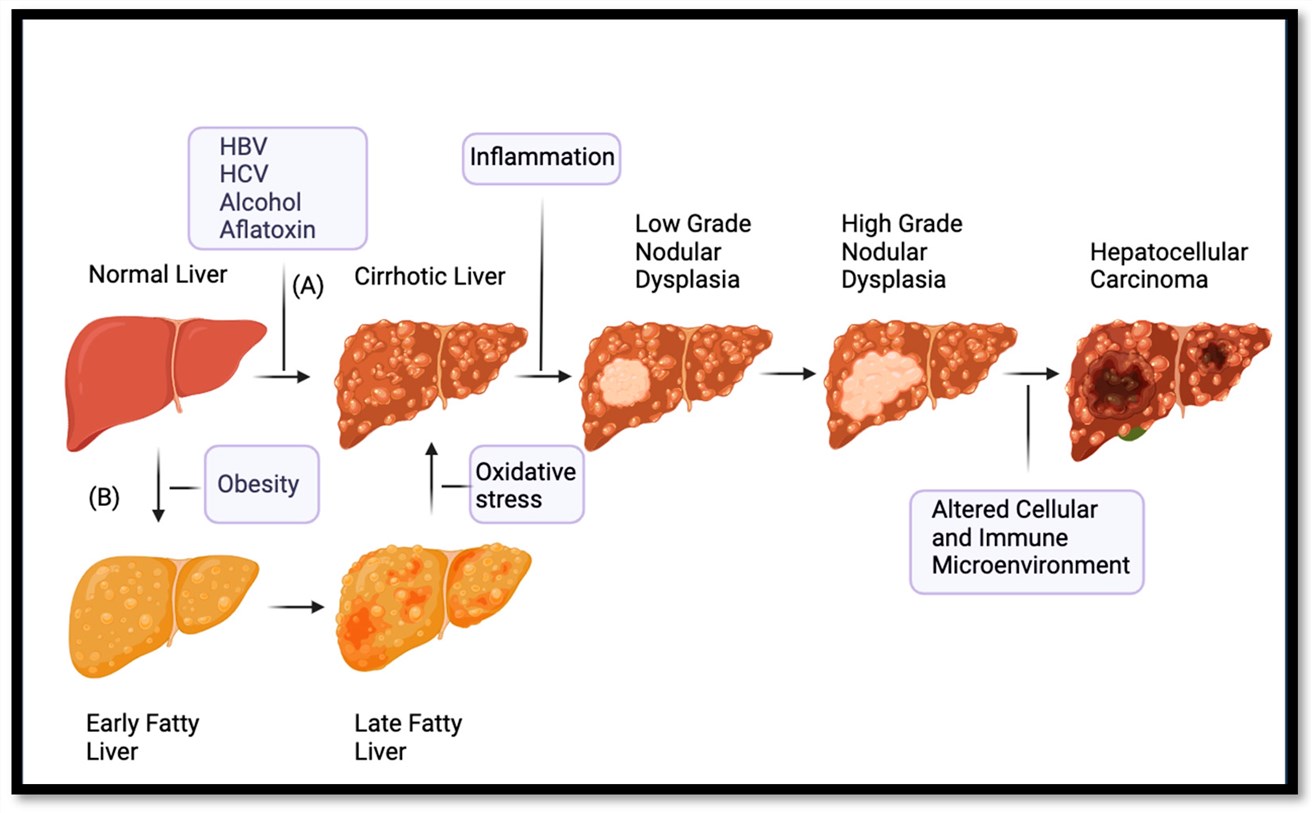

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is currently one of the most prevalent malignant solid tumors, constituting approximately 90% of all primary malignant liver tumors. The principal etiological agents contributing to HCC involve chronic infection by the hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus, alcohol intake, exposure to aflatoxin, as well as the gradual aggravation of fatty liver. Existing treatments, such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy, have demonstrated limited improvement in the overall survival of patients with advanced HCC, attributed to low response rates and high recurrence rates.

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) have been extensively investigated as novel cancer therapeutic agents in the treatment of HCC. Leveraging the genetic characteristics of HCC cells, researchers at Creative Biolabs have developed diverse oncolytic virus construction strategies based on OncoVirapy™ and offer verification services.

Factors predisposing to hepatocellular carcinoma

Tab.1 The causes of hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Carcinogenic Agent | |

|---|---|

| HBV |

|

| HCV | |

| Alcohol | Alcohol is one of the most prevalent etiological factors of liver disease globally. It can induce a diverse spectrum of direct hepatic injuries, encompassing hepatic steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. |

| Aflatoxin | Aflatoxin B1 metabolizes in vivo to an active form. It binds DNA, causing breaks and mutations, and boosts ROS. ROS-induced stress damages cell components, and AFB1 may trigger apoptosis or fuel tumor cell growth. |

Fig.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma that develops from cirrhosis or fatty liver.1,4

Fig.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma that develops from cirrhosis or fatty liver.1,4

Cancer-associated mutations involve multiple key pathways and genes. Mutations exist in the TERT promoter. The WNT pathway is activated, and TP53 is altered. JAK/STAT, RAS/MAPK, and PI3Ks/AKT/mTOR pathways are perturbed. Changes in FGF19, VEGF, and NF-κB lead to apoptosis evasion. Genes like ARID1A, involved in chromatin-remodeling epigenetic modifications, are also implicated, all crucial for cancer development.

Oncolytic Virus Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Tab.2 Viruses used in clinical trials to treat liver tumors or liver metastases.2,4

| Virus | OVT Product | Year | Modification of Virus | Phase | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV | NV1020 | 2010 | Deletion of UL56 internal repeat gene and UL24 gene expression. | Ⅰ/Ⅱ | Herpetic artery infusion |

| ADV | OBP-301 | 2023 | Attenuated type 5 ADV with an hTERT promoter | Ⅰ | IT |

| VV | JX-594, Pexa-Vec | 2019 | Inactivated thymidine kinase to express human GM-CSF and β-galactosidase | Ⅱb | IV |

| VSV | VSV-IFNβ-TYRP1 | 2023 | Express lFN-β and TYRP1 | Ⅰ | IV, IT |

| COX-A21 | V937, Viralytics | 2023 | Unmodified selected strain of CVA21 | Ⅰb | IV |

| Protoparvovirus H1 | ParvOryx | 2021 | Unmodified | Ⅱ | IV, IT |

-

HSV

Recent studies in mouse and non-human primate models with subcutaneously implanted human hepatocytes have focused on genetically engineering tumor-selective oHSV to express a human single-chain variable fragment that targets human PD-1. Mice treated with anti-PD-1-modified oHSV developed long-term T-cell response memory and reduced resistance to immunotherapy. -

Adenovirus

In a Phase Ⅰ trial, attenuated Ad5 is armed with OBP-301, whose expression is driven by the hTERT promoter. OBP-301 is expressed only in HCC cells, enhancing tumor selectivity. The hTERT promoter-internal ribosomal entry site interaction boosts OBP-301's replicability in cancer cells, leading to tumor cell lysis via viral replication. -

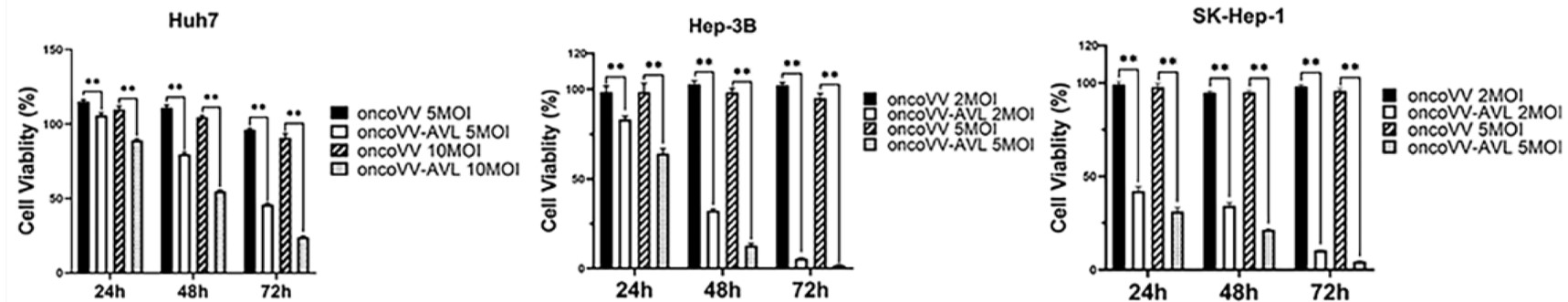

VACV

Aphrocallistes vastus lectin (AVL), a marine lectin frequently found in specific sponges and seaweeds, augments the cytotoxic effect of vaccinia virus on HCC cells through the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathways. Infection with VV-AVL significantly increases the apoptosis rate of HCC cells. It also significantly upregulates the expression of IFN-Ⅰ, markedly inhibits tumor growth, and reprograms HCC cell metabolism to enhance the production of ROS.

Erastin, a thoroughly studied ferroptosis inducer, has been demonstrated to trigger cell death in hepatic carcinoma cells, colorectal carcinoma cells, and ovarian carcinoma cells. When erastin is combined with vvDD (VVDD-IL15-Rα) in treatment, it brings about a marked decrease in tumor volume and the regression of tumor cells. -

COX-A

Coxsackievirus (COX) is a small cytolytic virus that pertains to the Enterovirus genus in the Picornaviridae family. The application of a biologically selected strain of Coxsackievirus A21, designated as V937, leads to the direct lysis of tumor cells that overexpress intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). During the therapeutic process for HCC, the co-administration of V937 and pembrolizumab substantially augments the release of IFN-α, IL-12, IFN-γ, MIP-1α, and IL-6. Pembrolizumab elevates the exhibition of ICAM-1 on the surface of tumor cells, and facilitates the heightened infectivity of HCC cells by V937 and the consequent tumor cell assault, thus inducing an anti-tumor effect.

Targeted delivery of oncolytic viruses (OVs) to the hepatic tissue

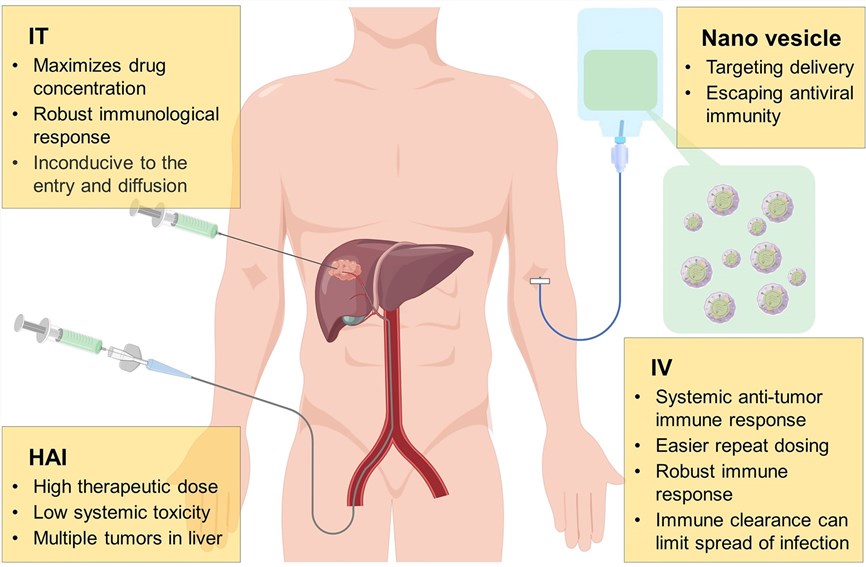

Fig.2 Administration methods for delivering oncolytic viruses to the liver.3,4

Fig.2 Administration methods for delivering oncolytic viruses to the liver.3,4

Typical delivery approaches for OVs involve hepatic arterial infusion (HAI), intratumoral (IT), and intravenous (IV) infusions.

- HAI, a routine approach in TACE and transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), enables the injection of high-dose therapeutic agents directly into tumors. This method effectively kills tumor cells while keeping systemic toxicity at low levels. However, it may trigger a systemic inflammatory response.

- Analogous to HAI, IT injection optimizes the dissemination of OVs within the tumor. Nevertheless, it has certain limitations. For instance, the dense and high-pressure microenvironment within the tumor may impede the entry and dissemination of OVs. Moreover, considering the liver's status as a visceral organ, the application of IT-injected OVs is relatively inconvenient.

- IV injection, characterized by high convenience and feasibility, promotes the widespread clinical application of OVs. It allows OVs to reach both systemic metastases and primary tumors, thereby enhancing the induced antitumor response. Nevertheless, owing to suboptimal target dissemination and the existence of neutralizing antibodies within the bloodstream, OVs are swiftly eliminated.

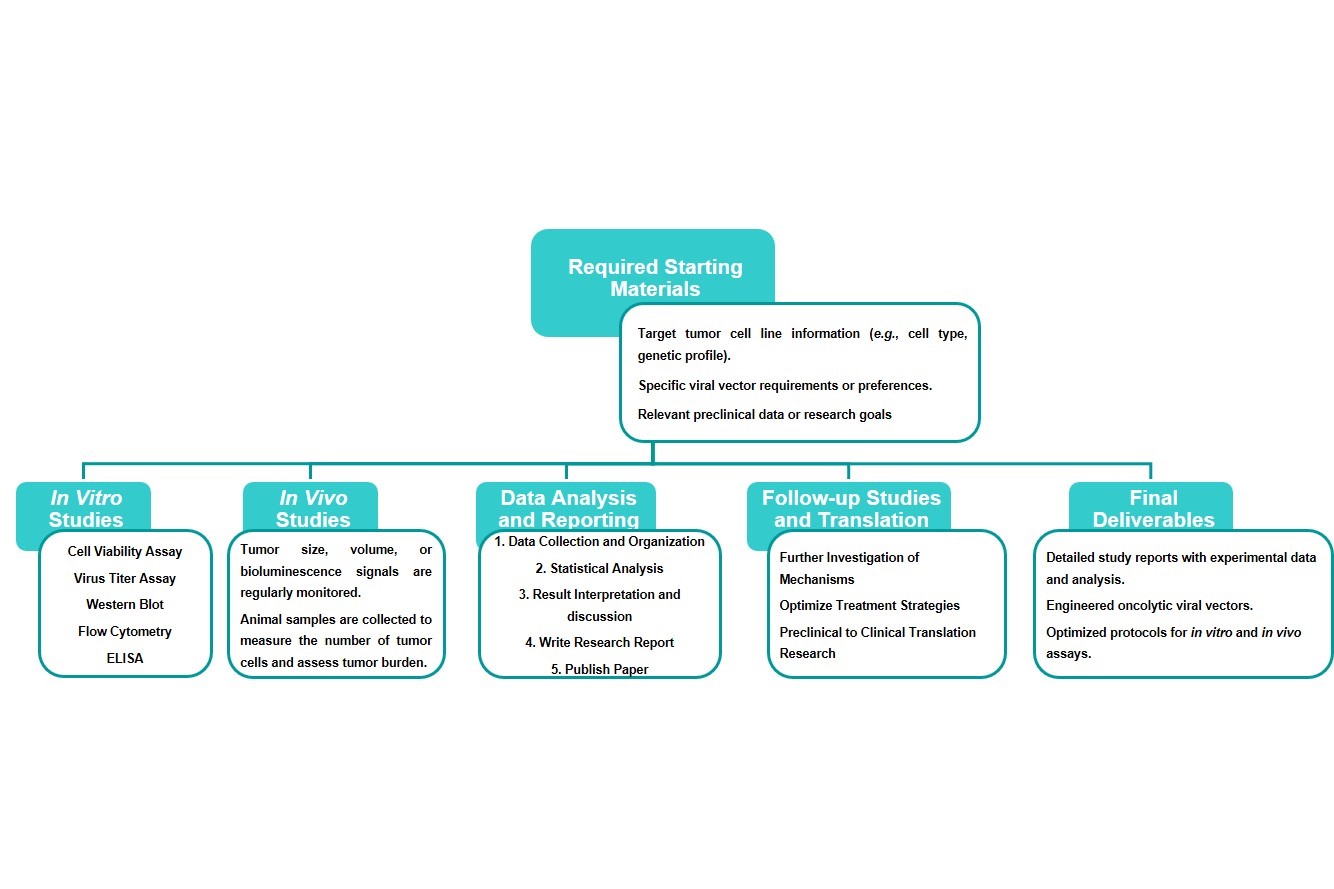

Workflow

Estimated Timeframe:

Pre-requirement communication: 1-2 weeks

Design and construction of oncolytic viruses: 3-4 weeks

Mass production of oncolytic viruses: 2-3 weeks

Function and properties of oncolytic viruses in vivo and in vitro: 3-4 weeks

Results analysis and test report: 1-2 weeks

Product delivery and shipping: 2-3 weeks

Case Study

The application of genetically-engineered oncolytic viruses in frequently used in vivo rabbit models and in vitro tumor cell line models of hepatocellular carcinoma has resulted in a substantial increase in tumor-destroying efficiency. Data extracted from numerous research articles provide valuable perspectives on its favorable prospects for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy.

Fig.3 MTT assay is used to detect the cell viability of HCC cells.5

Fig.3 MTT assay is used to detect the cell viability of HCC cells.5

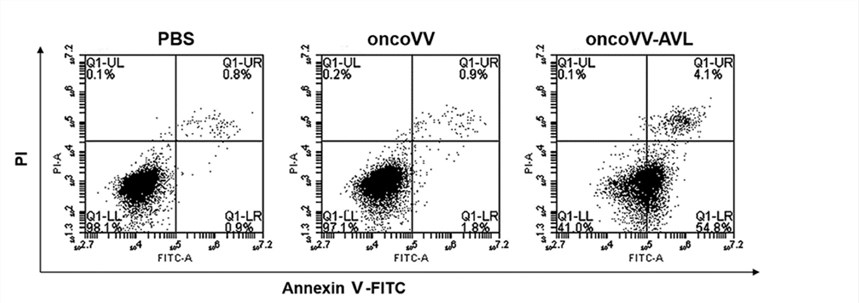

Fig.4 Flow cytometry is used to detect the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells.5

Fig.4 Flow cytometry is used to detect the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells.5

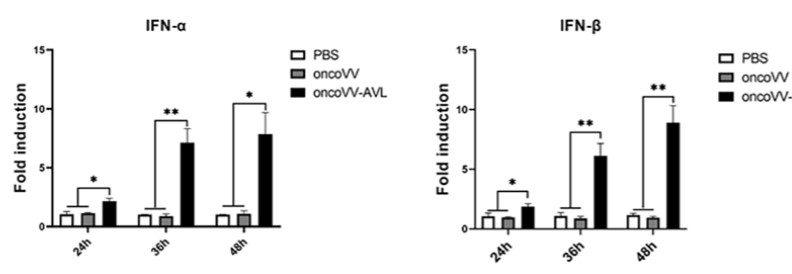

Fig.5 qRT-PCR is used to detect the expression of target genes.5

Fig.5 qRT-PCR is used to detect the expression of target genes.5

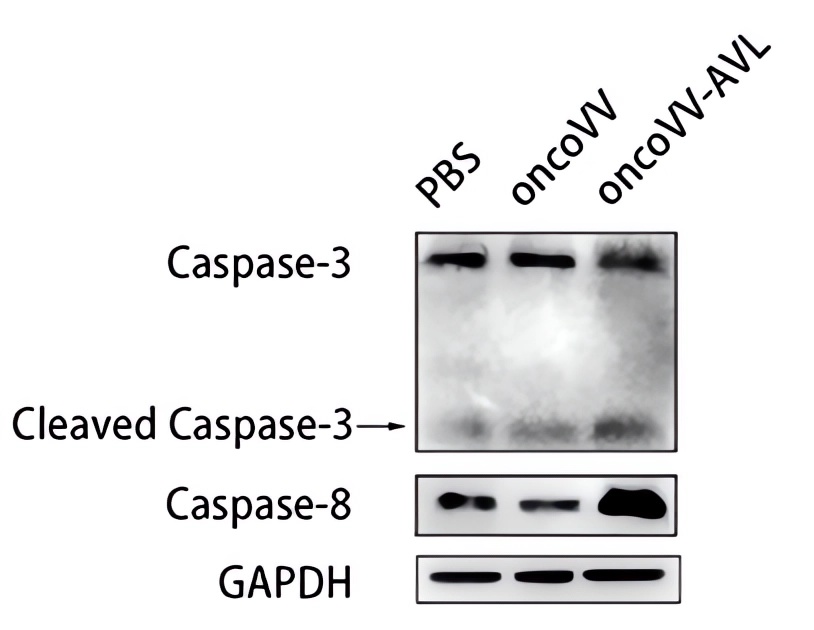

Fig.6 Western Blot is used to detect the expression levels of related proteins.5

Fig.6 Western Blot is used to detect the expression levels of related proteins.5

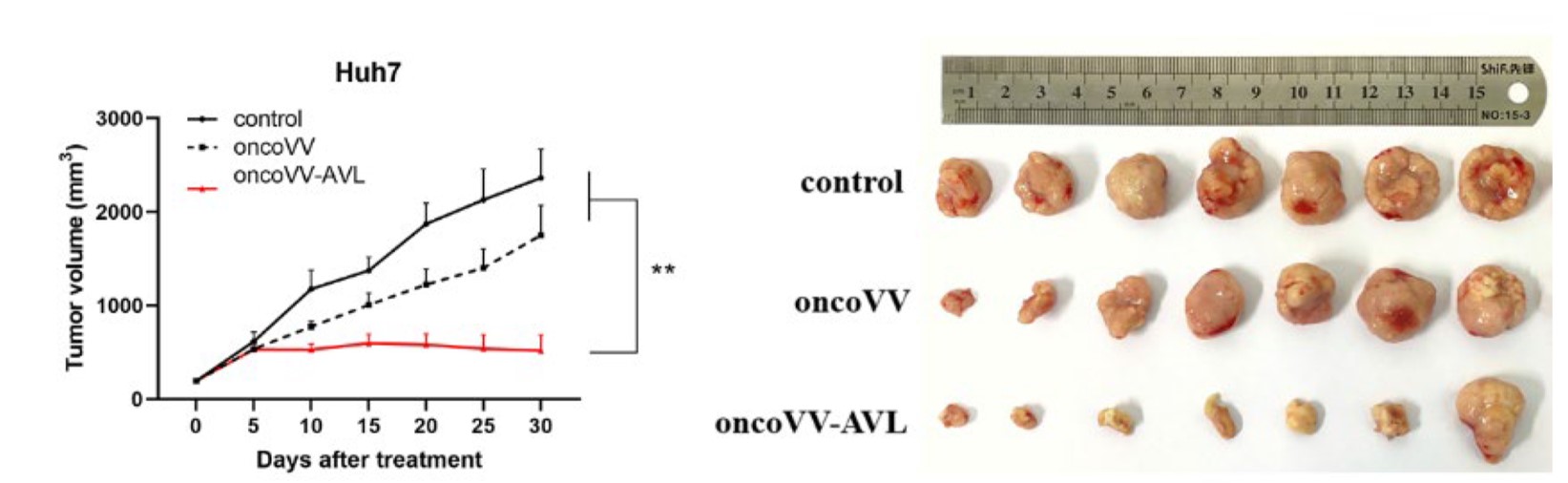

Fig.7 Oncolytic viruses reduce liver tumor size.5

Fig.7 Oncolytic viruses reduce liver tumor size.5

References

- Coffin, Philip, and Aiwu He. "Hepatocellular carcinoma: past and present challenges and progress in molecular classification and precision oncology." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24.17 (2023): 13274. DOI: 10.3390/ijms241713274

- Hua, Xuesi, et al. "Progression of oncolytic virus in liver cancer treatment." Frontiers in Oncology 14 (2024): 1446085. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1446085

- Zhu, Licheng, et al. "Recent advances in oncolytic virus therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma." Frontiers in oncology 13 (2023): 1172292. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1172292

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Jiang, Riqing, et al. "Oncolytic vaccinia virus harboring aphrocallistes vastus lectin inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells." Marine Drugs 20.6 (2022): 378. DOI: 10.3390/md20060378. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, reformat the picture.