Albumin-Based Delivery Strategies: Benefits and Biomedical Applications

Traditional drug delivery systems often face challenges in stability and targeting efficiency. Currently, these challenges are addressed by using the albumin-based delivery strategies. In this review, Creative Labs will take you through the mechanistic principles and applications of the albumin-based delivery systems.

Introduction to Albumin-Based Delivery Systems

What Is Albumin and Why Use It for Drug Delivery?

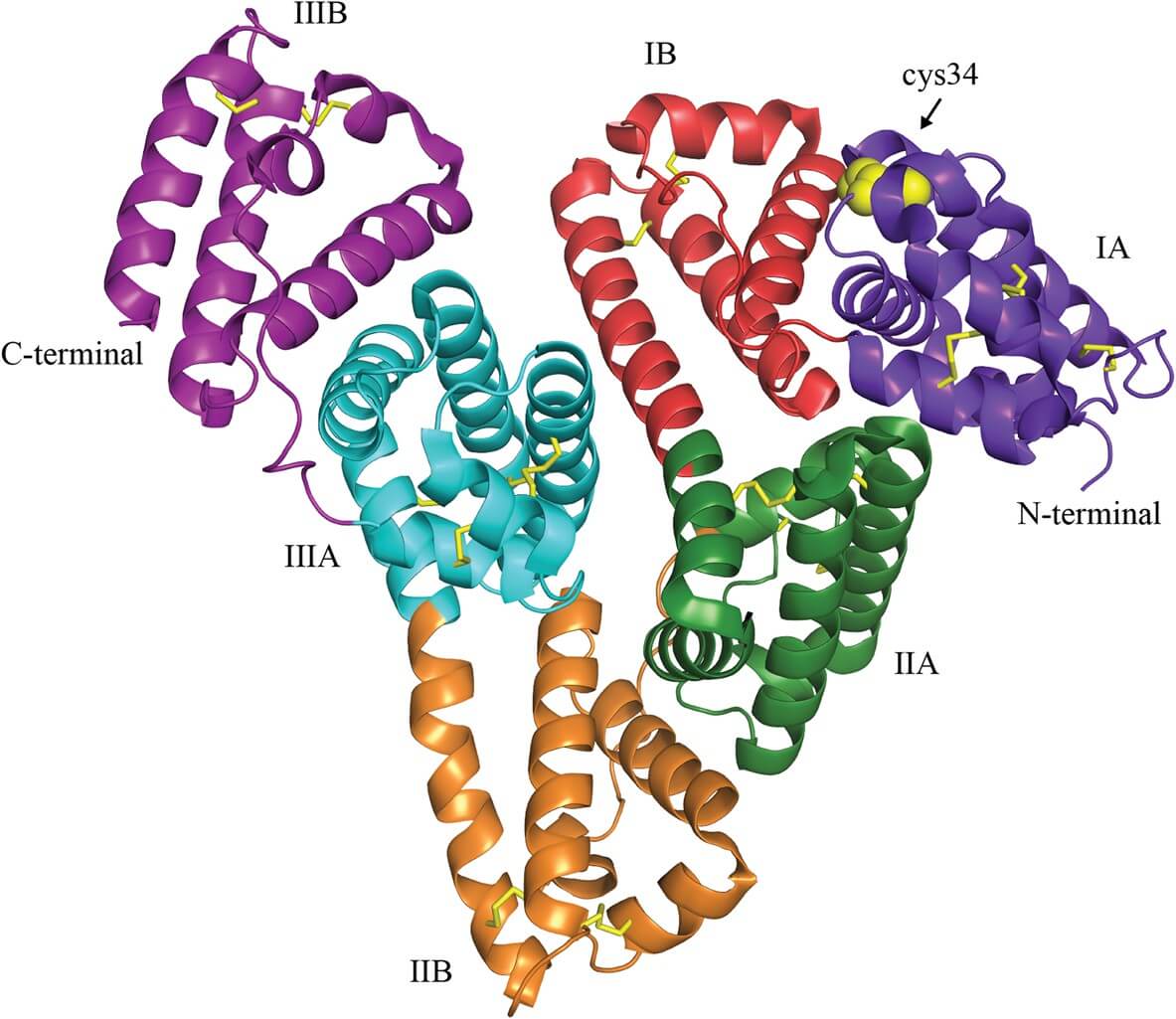

Albumin is the most abundant plasma protein (30–50 mg/ml) in human serum. It is a 66.5 kDa-unglycosylated globular protein primarily synthesized in the liver. It exhibits a prolonged circulating half-life (~19 days in humans) via neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated recycling, maintains blood oncotic pressure, and naturally transports lipophilic substances (e.g., fatty acids, hormones) via seven fatty acid binding sites and a free cysteine (C34) for conjugation (Figure 1). These structural and functional traits make it ideal for drug delivery. There are five key reasons for researchers and pharmaceutical companies to use albumin-based drug delivery:

As albumin is a natural protein, it rarely causes immune rejection.

Albumin can remain in the bloodstream for nearly 19 days. Therefore, its long circulation enables sustained drug exposure.

Drugs can accumulate in solid tumors via passive targeting.

Because albumin can interact with FcRn, GP60 (also known as albumin-binding protein), and SPARC receptors, active targeting is further enabled by interactions with tumor-overexpressed proteins like GP60, SPARC, and FcRn, allowing facilitated transcytosis and intracellular uptake.

Drugs can be attached to albumin or encapsulated within albumin-based carriers. Albumin can be modified through covalent conjugation, noncovalent binding, or nanoformulation to address key limitations of conventional chemotherapeutics, such as drug solubility, systemic toxicity, and tumor penetration.

Fig.1

Crystal structure of human serum albumin1.

Fig.1

Crystal structure of human serum albumin1.

Mechanisms of Albumin-Based Drug Delivery1–4

Passive Accumulation (EPR Effect)

Albumin-based drug delivery systems enable passive accumulation in tumor tissues by leveraging the EPR effect. Solid tumors are characterized by leaky vasculature with interendothelial gaps (50–1000 nm) and impaired lymphatic drainage. Unlike healthy vasculature, where tight junctions between endothelial cells block nanoparticle penetration, tumor blood vessels enable albumin nanoparticles to accumulate in the tumor interstitium over time. Their loose interendothelial gaps can allow nanoparticles (e.g., albumin-bound paclitaxel, ~130 nm) to extravasate, and their impaired lymphatic drainage can prevent rapid clearance of these particles. A typical example is the nab-paclitaxel, which achieves 33% higher intratumoral paclitaxel concentrations in breast tumor xenografts by leveraging the EPR effect, compared to solvent-based paclitaxel. Moreover, many recent studies have suggested that the EPR effect of albumin varies across tumor types. In this scenario, strategies such as combining albumin nanoparticles with nitric oxide (NO)-releasing agents (e.g., S-nitrosated HSA dimer) can augment vascular permeability, thereby enhancing passive accumulation, even in tumors with a low baseline vascular leakiness.

Receptor-Mediated Transport (Active targeting)

Receptor interactions are key to active targeting and prolonged circulation of albumin-based systems. There are mainly three receptor interactions involved in active targeting.

-

GP60 (albondin)

GP60 (albondin) is a 60 kDa glycoprotein overexpressed on tumor endothelial cells. It mediates albumin transcytosis via the formation of caveolae (membrane invaginations). After binding to albumin, GP60 recruits caveolin-1 to form caveolae, which transport albumin across the endothelial barrier into the tumor interstitium. -

SPARC (secreted protein, acidic, rich in cysteine)

SPARC (secreted protein, acidic, rich in cysteine) is a matricellular protein abundant in tumor microenvironments. Once drug-loaded nanoparticles enter the interstitium, SPARC can concentrate them in tumor cells by binding to albumin, therefore promoting tumor uptake. It has been shown that SPARC expression correlates with treatment efficacy. In head and neck cancer patients, SPARC-positive tumors show 83% response to nab-paclitaxel, compared with 25% in SPARC-negative tumors. -

FcRn receptor

The FcRn prolongs albumin's circulatory half-life (~19 days in humans) by recycling albumin back into circulation. FcRn can bind to albumin within acidic endosomes (pH <6.5), diverting it from lysosomal degradation and releasing it back into the bloodstream at physiological pH (7.4).

Drug Binding & Release

By leveraging its specific structure, albumin can bind to hydrophobic drugs in its binding pockets and release them gradually in target tissues, thereby minimizing related systemic toxicity. It has a three-domain (I–III) globular structure with ten critical binding sites. Seven are distributed asymmetrically across the protein and function as fatty acid binding sites. The remaining three include the free thiol located at the Cys34, and two hydrophobic pockets, Sudlow sites I (subdomain IIA) and II (subdomain IIIA). By binding to these hydrophobic pockets, hydrophobic drugs (e.g., paclitaxel, docetaxel) can load onto the albumin via van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. For example, paclitaxel can bind to the hydrophobic cavities of albumin in an amorphous state, thereby avoiding crystallization and improving solubility. Drug release can then be triggered by tumor-specific conditions. In tumors, the acidic microenvironment (pH 5.0–6.5) enables the disruption of albumin-drug interactions, and high glutathione (GSH) levels facilitate the disulfide bond cleavage of modified albumin, resulting in intracellular payload release. Compared with free doxorubicin, doxorubicin-albumin conjugate exhibited a 50% reduction in cardiotoxicity.

Types of Albumin-Based Drug Delivery Systems

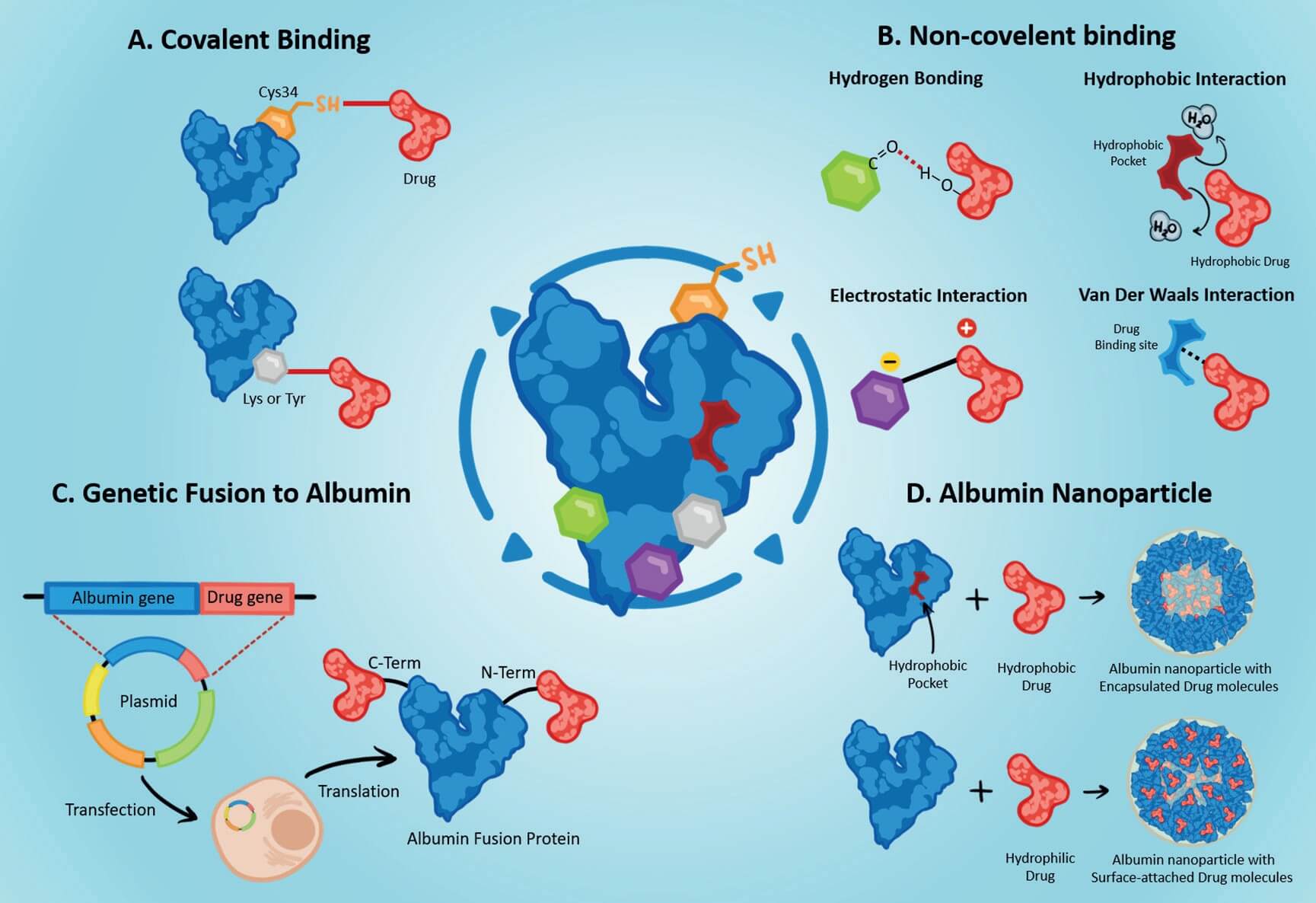

According to different mechanisms, there are four types of albumin-based drug delivery Systems (Figure 2). Each type leverages different structural and functional traits, enabling albumin's role as a drug delivery carrier.

Covalent binding

Covalent binding links drugs to albumin via specific residues, forming stable conjugates for controlled release. For example, third-generation EGFR TKIs can covalently bind to albumin's Lys195/199, and acid glucuronides from drug glucuronidation can form bonds with albumin's NH2, OH, or SH groups. It ensures targeted payload release by influencing the drug clearance and metabolism.

Noncovalent binding

Noncovalent binding relies on weak interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, van der Waals) for the reversible drug-albumin association. Key noncovalent binding sites include Sudlow sites I (for warfarin, phenylbutazone) and II (for ibuprofen, diazepam), and seven fatty acid-binding sites. For instance, insulin can bind noncovalently to albumin through a C14 fatty acid chain. The reversible binding slows the absorption and distribution of the insulin, resulting in its long-lasting and steady drug effect.

Albumin fusion

Albumin fusion utilizes genetic engineering to form fusion proteins by linking target proteins (e.g., GLP-1, coagulation factor IX) to the N- or C-terminus of HSA. Although the behavior of the fusion protein is hard to predict, peptide linkers can optimize stability and biological activity. For instance, in the treatment of hemophilia B, the coagulation factor IX is fused to HAS for a fivefold extended half-life.

Albumin nanoparticles

Albumin nanoparticles can encapsulate drugs (especially hydrophobic ones) via methods such as desolvation, therefore protecting them from degradation, and enabling their controlled release and enhanced tumor penetration. A typical example of this is nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel, the first nanotechnology-based cancer treatment. It leverages several natural properties of albumin in drug delivery, including the EPR effect for passive tumor accumulation, GP60-mediated transcytosis across the endothelium, and SPARC binding for intratumoral enrichment.

Fig.2 Types of

albumin-based drug delivery systems4.

Fig.2 Types of

albumin-based drug delivery systems4.

Advantages and Challenges of Albumin-based Drug Delivery

Advantages

As a natural human plasma protein, albumin exhibits excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability. Its degradation products are non-toxic and can be easily metabolized or excreted by the body. Therefore, there are no long-term bioaccumulation risks.

As mentioned in the introduction, relying on the FcRn-mediated recycling mechanism, albumin can help drugs escape lysosomal degradation and get back to the bloodstream. In humans, the circulatory half-life of the drug-albumin complex can be extended to approximately 19 days, resulting in prolonged systemic drug exposure.

There are multiple specific binding sites on albumin. These specific binding sites can allow for the binding of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs.

According to different therapeutic needs, albumin can be fabricated into diverse drug delivery systems. For example, albumin-drug conjugates (e.g., aldoxorubicin, methotrexate-HSA) can enable controlled drug release. Albumin nanoparticles can be used for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs (e.g., gemcitabine-loaded albumin nanoparticles). Albumin hydrogels can be applied for localized, sustained release in tumor therapy or tissue engineering.

Challenges

As albumin is an inherently protein, its drug-binding capacity and controlled release profiles can be affected by reversible conformational changes through various environmental factors, such as pH fluctuations, oxidative/reductive conditions, and organic solvents. For instance, albumin aggregation could be triggered by high temperatures and repeated freeze-thaw cycles, resulting in immunogenic responses and reduced drug-loading efficiency.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), as an alternative reagent to albumin, is commonly used in preclinical studies. It may induce mild immunogenic responses in humans.

Albumin's multiple binding sites may cause competitive binding between co-administered drugs. High-affinity drugs could displace low-affinity ones from albumin, thus altering the pharmacokinetic behavior of the displaced ones. As a result, unexpected drug toxicity is increased.

Although many preparation methods are available for albumin production, the production processes are complex and hard to scale up. The batch-to-batch differences in particle size, drug-loading rate, and release kinetics can be influenced by various preparation parameters, including cross-linker concentration and homogenization pressure.

Biomedical Applications of Albumin Formulations

Albumin is already widely used in biomedicine (Table 1).

Table 1 Biomedical Applications of Albumin-based Drug Delivery Systems.

| Application Field | Specific cases | Specific Formulations | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Breast cancer | nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel |

|

| Pancreatic cancer | |||

| Lung cancer | |||

| Critical Care | Hypoalbuminemia | Human serum albumin (5%, 20%, 25%) |

|

| Sepsis/shock | |||

| Burns | |||

| Liver & Kidney Disorders | Liver diseases | Human serum albumin infusions |

|

| Kidney diseases | |||

| Ophthalmology | retinal diseases | Albumin-based sustained-release microspheres |

|

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The future of albumin-based drug delivery is shaped by several innovations.

Recombinant albumin production

Traditional human serum-derived albumin could carry donor-related risks (e.g., pathogen transmission), causing safety concerns. The production of recombinant human albumin (rHSA) via yeast or bacterial systems can mitigate these risks. Moreover, it ensures batch consistency, allowing for scale-up production.

Albumin fusion proteins

To extend the half-life of biologics, scientists are attempting to genetically fuse various therapeutic proteins to the N- or C-terminus of albumin.

Personalized medicine

As there are many types of albumin-based drug delivery systems, albumin carriers can be tailored according to patient-specific tumor traits for proximal targeted drug delivery. For instance, SPARC-positive pancreatic cancers may benefit more from nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel.

Gene and RNA delivery

Due to its excellent biocompatibility and stability, albumin is an ideal carrier for the delivery of nucleic acids. It has been proven that it can protect siRNA/plasmids from nuclease degradation.

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What diseases are commonly treated with albumin formulations?

Cancer, sepsis, liver, kidney, and retinal diseases.

Is recombinant albumin safer than plasma-derived albumin?

Yes. Compared with plasma-derived albumin, recombinant albumin can avoid risks such as viral transmission and ensure higher batch-to-batch consistency.

What are the latest market trends for albumin drug delivery?

It is expected that the production of recombinant albumin and its applications in personalized therapies and oncology will skyrocket in the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Albumin-based drug delivery systems represent a powerful platform for modern therapeutics. It confers many properties in safety, efficiency, and versatility. With established biomedical use and promising innovations such as recombinant albumin production, this field is expected to be widely applied in the fields of oncology and personalized medicine.

Creative Biolabs is dedicated to advancing albumin-based drug delivery technologies, offering researchers state-of-the-art platforms, tailored services, and dependable expertise.

References

- Larsen, M. T., Kuhlmann, M., Hvam, M. L. & Howard, K. A. "Albumin-based drug delivery: harnessing nature to cure disease." Moland Cell Ther 4, 3 (2016). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40591-016-0048-8 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Van De Sande, L., Cosyns, S., Willaert, W. & Ceelen, W. "Albumin-based cancer therapeutics for intraperitoneal drug delivery: a review." Drug Delivery 27, 40–53 (2020). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10717544.2019.1704945

- Hassanin, I. & Elzoghby, A. "Albumin-based nanoparticles: a promising strategy to overcome cancer drug resistance." CDR 68 (2020). https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/cdr.2020.68

- Al-Harthi, S. et al. "Albumin as a Drug Delivery System: Mechanisms, Applications, and Innovations." in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery - A Comprehensive Overview [Working Title] (IntechOpen, 2025). https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/1217582 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

Created in September 2025