Passive Targeting Delivery Strategies: A Complete Beginner-Friendly Guide

Passive targeting delivery strategies offer one of the simplest yet most powerful ways to guide drugs and nanoparticles directly to diseased tissues by using the body s own physiology. Instead of relying on complex ligands, these systems take advantage of features such as leaky blood vessels and poor lymphatic drainage to raise drug levels where they are needed most. As the demand for safer, more efficient formulations grows, passive targeting is becoming a core pillar of modern nanomedicine. This article breaks down the science in clear, beginner-friendly language while showing how Creative Biolabs supports smarter, next-generation delivery solutions.

What Is Passive Targeting in Drug Delivery?

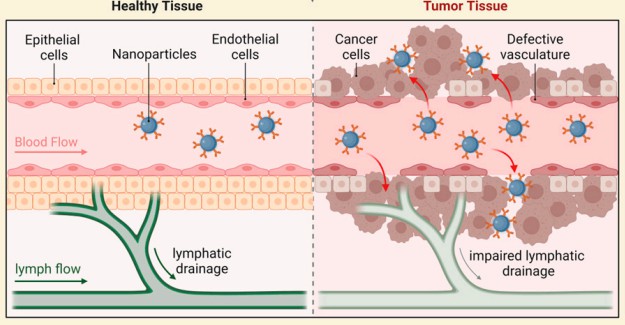

Passive targeting in drug delivery means using the body s own biology to guide drugs or nanoparticles to the right place. Instead of adding special ligands, the system relies on how blood flows, how "leaky" blood vessels are, and how well tissues clear fluids. In many tumors and inflamed tissues, the blood vessels are abnormal. They often have gaps between cells and poor lymphatic drainage (Figure 1). Because of this, nanocarriers and macromolecules that stay in the blood for a long time can slowly slip into these tissues and then remain there longer than in many healthy organs. This simple but powerful idea sits at the heart of passive targeting delivery strategies. In oncology, passive targeting is strongly linked to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. When teams design nano-formulations for cancer, they often aim to take advantage of this effect first, and then they may add more complex features later.

Fig.1 The mechanism of the tumor targeting via the EPR effect.2

Fig.1 The mechanism of the tumor targeting via the EPR effect.2

The EPR Effect Explained Simply

The EPR effect is the key reason passive targeting works so well in many preclinical tumor models.

- Enhanced permeability means tumor blood vessels are leaky.

- Retention means lymph drainage is poor, so materials that enter the tumor tend to stay.

Nanoparticles and macromolecular drugs above a certain size do not pass easily through normal tight blood vessels. However, they can more easily pass through the larger gaps found in many tumor vessels. Once inside the tumor space, they are not cleared quickly, so their concentration can slowly rise over time. In human patients, the EPR effect is real but often weaker and more variable than in animal models. Therefore, smart formulation design and careful optimization are essential to get real benefit from passive tumor targeting.

How Passive Targeting Works: Step-by-Step

You can think of passive targeting as a simple stepwise journey:

1. Injection or infusion

The nano-formulation enters the bloodstream, usually by intravenous injection.

2. Circulation in the blood

A well-designed carrier avoids fast kidney clearance and rapid uptake by the immune system, so it stays in the blood for a longer time.

3. Reaching abnormal vessels

As the blood flows through tumors or chronically inflamed regions, the nanocarriers encounter leaky vessels.

4. Extravasation into the tissue

Through the gaps in these vessels, nanoparticles slip out of the bloodstream and move into the surrounding tissue.

5. Retention in the diseased site

Because lymph drainage is poor, the nanoparticles remain in the tumor or inflamed tissue and accumulate over hours or days.

This flow shows why passive targeting delivery strategies always start with long circulation and suitable particle properties. Without those, the system cannot fully exploit the EPR effect.

Passive vs Active Targeting: Clear Comparison

Many people search for the difference between passive and active targeting. Table 1 highlights the key differences between passive and active targeting in drug delivery. Passive targeting relies on natural physiology such as the EPR effect, while active targeting uses ligands for receptor binding. It also compares design complexity, deposition mechanisms, and typical applications across tumors, inflamed tissues, and receptor-rich cells.

Table 1 Common preparation methods.

| Feature | Passive Targeting | Active Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Main driver | Physiology (EPR, inflammation, MPS uptake) | Ligand–receptor or affinity interactions |

| Need for ligands | No | Yes (antibodies, peptides, small molecules, etc.) |

| First step of deposition | Directly from blood via leaky vessels | Often still depends on initial passive accumulation |

| Design complexity | Lower, simpler formulation | Higher, needs ligand chemistry and extra testing |

| Typical use cases | Tumors, liver, spleen, and inflamed or infected tissues | Receptor-rich tumors or cells needing strong cell-level uptake |

In real-world projects, these two strategies are not mutually exclusive. Instead, active targeting often builds on a strong passive targeting base.

Where Passive Targeting Works Best

Passive targeting works especially well where the vasculature or immune environment is abnormal:

-

Solid tumors

Most classic EPR examples come from tumors with leaky vessels and poor lymph drainage. Many approved nano-oncology products rely on this. -

Chronic inflammation and infection

Inflamed tissues can show increased blood flow, higher permeability, and strong immune cell activity, which together promote nanoparticle accumulation. -

Liver and spleen

These organs belong to the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) and naturally filter foreign particles, especially when they are not fully "stealth".

When choosing a platform, it is important to match the carrier type and passive targeting route to the indication. For example, a liver-directed program may use different design rules than a solid tumor project. Creative Biolabs can guide this selection, from lipid-based systems to polymeric and inorganic carriers, based on the dominant passive targeting pathway in each disease area.

Nanocarriers That Rely on Passive Targeting

Several major nanocarrier families mainly make use of passive targeting:

-

Liposomes and PEGylated liposomes

These tiny lipid vesicles can carry hydrophilic or hydrophobic drugs. PEG on the surface helps them stay longer in the bloodstream. -

Polymeric nanoparticles and micelles

Biodegradable polymers can self-assemble into particles or micelles that encapsulate drugs and slowly release them. -

Albumin-bound and polymer-drug conjugates

Here, the drug is attached to albumin or a synthetic polymer, which changes its size and distribution in the body. -

Inorganic nanoparticles

Iron oxide, gold, and mesoporous silica particles can be engineered with coatings to extend circulation and adjust surface behavior.

At Creative Biolabs' targeted delivery services, these platform types can be customized in terms of size, surface charge, coating, and release rate to fit each client's passive targeting goals.

Real-World Examples of Passively Targeted Nanomedicines

Several marketed products demonstrate how passive targeting can improve therapy:

-

Liposomal doxorubicin

Encapsulating doxorubicin in a PEGylated liposome helps it circulate longer and accumulate in tumors, while reducing heart toxicity. -

Albumin-bound paclitaxel

Paclitaxel linked to albumin uses natural albumin transport and tumor uptake mechanisms to enhance exposure and reduce solvent-related side effects. -

PEGylated nanocarriers

Various PEGylated liposomal or polymeric products show improved pharmacokinetics, better tumor deposition, and a safer toxicity profile than their free-drug versions.

These examples show that even without added ligands, passive targeting delivery strategies can create real clinical value when they are designed and tested carefully.

Challenges and Limitations of Passive Targeting

Although passive targeting is powerful, it is not perfect.

- First, the strength of the EPR effect varies between tumor types and patients. Some tumors are highly leaky, while others are not, which leads to different levels of benefit in clinical trials.

- Second, passive targeting is not completely specific. Other tissues with leaky vessels or high immune activity, such as the liver and spleen, can also accumulate nanocarriers. This may still be useful for some indications, but it can limit tumor selectivity.

- Third, there is a translation gap between animal models and humans. Many nano-formulations show strong passive targeting in mice but only modest gains in patients. This gap motivates more advanced strategies, such as combining passive and active targeting or temporarily boosting the EPR effect.

Because of these challenges, smart experimental design, careful patient selection, and robust analytics are essential parts of any passive targeting program.

Enhancing Passive Targeting: Next-Generation Strategies

New research directions aim to make passive targeting more reliable and powerful:

-

EPR enhancers and vascular modulation

Techniques such as mild hyperthermia, photodynamic therapy, or vasoactive drugs can temporarily increase tumor blood flow and vessel permeability. In some preclinical models, this leads to much higher nanoparticle delivery. -

Combining passive and active targeting

Many groups now design carriers that first rely on EPR to reach the tumor, and then use ligands or stimuli-responsive elements for deeper penetration and better cell uptake. -

Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers

pH-sensitive, redox-sensitive, enzyme-responsive, or externally triggered systems can further refine when and where drugs are released.

These emerging tactics show that passive targeting delivery strategies are not static. Instead, they are becoming more dynamic, layered, and tailored to real clinical challenges.

How to Design Better Carriers for Passive Targeting (Beginner-Friendly Breakdown)

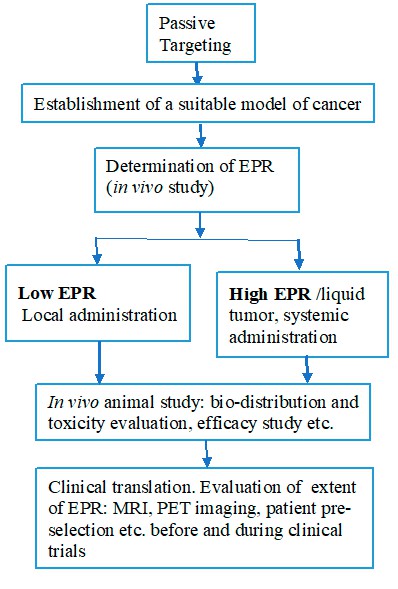

Creative Biolabs acts as a specialized partner for teams that want to turn passive targeting concepts into working formulations. The basic workflow for the development of the EPR-based drug delivery system is shown in Figure 2.

Fig.2 The workflow of the EPR-based delivery development.1

Fig.2 The workflow of the EPR-based delivery development.1

Except that our targeted delivery platform supports:

- Custom liposomal, polymeric, and inorganic nanocarriers optimized for passive accumulation.

- Rational size, charge, and coating design to match the intended indication and route.

- Module-based system design, where clients can build up their delivery system step by step using our module delivery systems.

- In vitro and in vivo evaluation, including stability, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and efficacy readouts.

Because our approach is modular, clients can start with a passive targeting base and later add active ligands or stimuli-responsive features without redesigning everything from scratch.

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What is passive targeting in drug delivery?

Passive targeting is the natural build-up of drugs or nanocarriers in certain tissues due to physiological features such as leaky blood vessels, poor lymph drainage, or strong immune uptake. It does not require any special ligand on the carrier surface.

How does the EPR effect support passive tumor targeting?

The EPR effect arises because many tumors have abnormal, leaky vessels and weak lymph drainage. Long-circulating nanoparticles can leak into the tumor and then stay there longer than in most healthy tissues.

What is the main difference between passive and active targeting?

Passive targeting depends on the body's own vascular and clearance features, while active targeting uses added ligands that bind to specific receptors on cells to boost binding and uptake.

Which nanocarriers mainly use passive targeting?

PEGylated liposomes, polymeric micelles, polymer–drug conjugates, albumin-bound drugs, and many inorganic nanoparticles are designed to use long circulation and the EPR effect as their primary targeting mechanisms.

Why is passive targeting important for cancer therapy?

Passive targeting can increase drug levels in tumors and lower exposure in healthy tissues. This balance may help improve efficacy while reducing common side effects linked to traditional chemotherapy.

Can passive targeting be combined with active targeting?

Yes. In fact, many advanced designs use passive targeting to bring the carrier to the tumor and active targeting to fine-tune uptake into specific cells inside the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusion

Passive targeting delivery strategies turn basic features of disease biology into powerful allies. By using leaky tumor vessels, poor lymph drainage, and altered immune activity, well-designed nanocarriers can deliver higher drug levels to tumors and other diseased tissues, often with better safety than free drugs. However, the EPR effect is not the same in every patient, and passive targeting alone may not always be enough. Therefore, the most successful programs usually combine careful carrier design, strong analytics, and, in many cases, hybrid strategies that blend passive and active targeting.

If you are planning or running a drug-delivery program and want to explore how passive targeting could unlock more value from your payload, Creative Biolabs is ready to help. Our experienced team can support you from early concept and carrier selection to a fully modular system design and preclinical evaluation.

Get in touch with Creative Biolabs today to discuss your passive targeting delivery strategy and start building a smarter, safer nano-formulation for your next program.

References

- Subhan, M. A., Yalamarty, S. S. K., Filipczak, N., Parveen, F. & Torchilin, V. P. "Recent Advances in Tumor Targeting via EPR Effect for Cancer Treatment." JPM 11, 571 (2021). https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/11/6/571. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Vagena, I.-A., Malapani, C., Gatou, M.-A., Lagopati, N. & Pavlatou, E. A. "Enhancement of EPR Effect for Passive Tumor Targeting: Current Status and Future Perspectives." Applied Sciences 15, 3189 (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/15/6/3189. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.