Micelle-Based Targeted Delivery Strategy

Micelle-based targeted delivery represents a promising nanotechnology approach that enhances the solubility, stability, and site-specific accumulation of therapeutic agents. Formed through the self-assembly of amphiphilic molecules, these nanoscale carriers provide an efficient means to deliver both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs with improved pharmacokinetic profiles. In this review, Creative Biolabs provides a comprehensive overview of micelle design principles, classification, and emerging strategies that drive their application in modern drug delivery research.

Introduction to Micelle-Based Targeted Delivery

What Are Micelles?

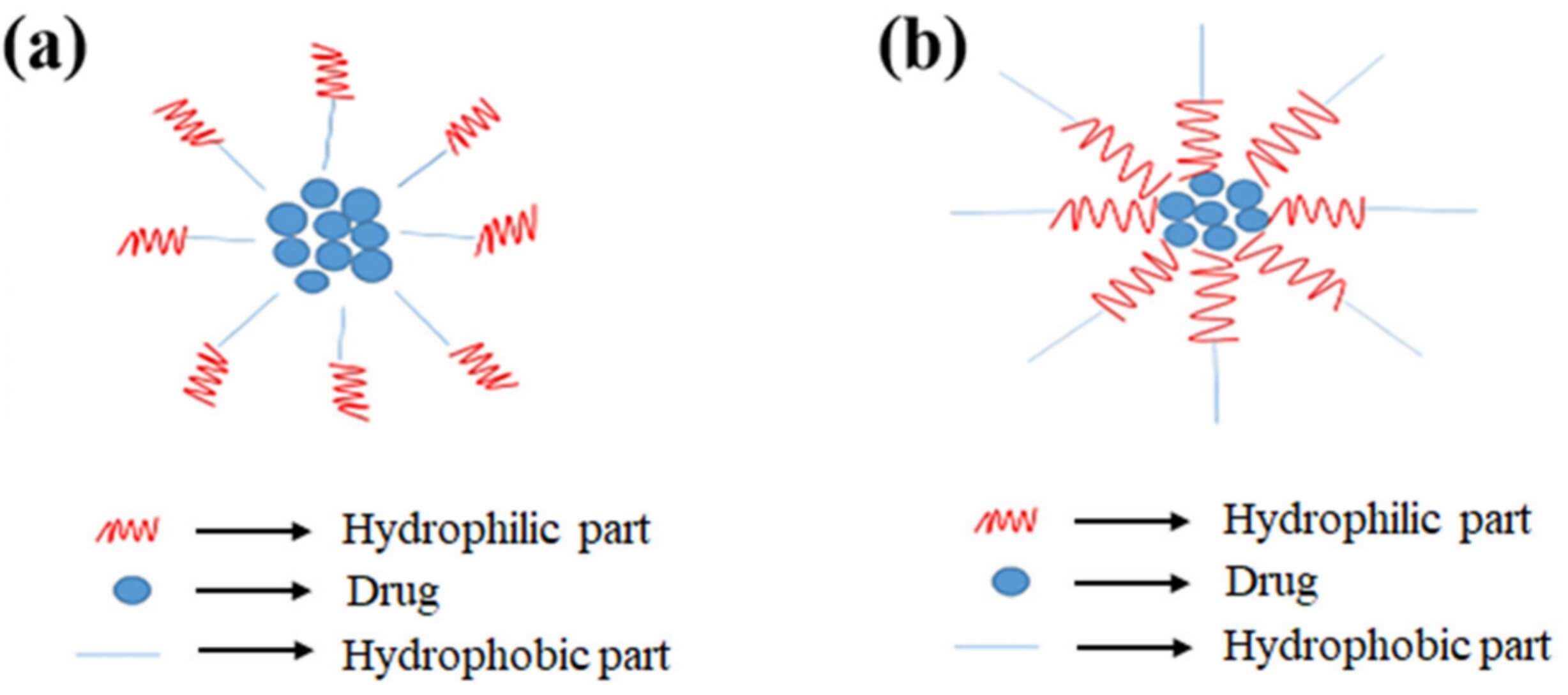

Micelles are self-assembling nanosized colloidal structures (usually 5-100 nm in diameter), which are formed by amphiphilic molecules (with hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments) in solvents. They boast signature core-shell architectures (Figure 1). Based on their structure, micelles can be classified into two types: regular and reverse micelles. In aqueous solutions, regular micelles are formed. These micelles orient their hydrophilic segments (e.g., polyethene glycol, PEG) outward as a protective shell and hydrophobic segments (e.g., polylactic acid, PLA) inward to form a hydrophobic core. Reversed Micelles are assembled in non-aqueous solvents (e.g., chloroform, oleic acid). Their structure is inverted, featuring a hydrophobic shell and a hydrophilic core, which facilitates the loading of hydrophilic drugs/proteins. This makes them ideal for delivering hydrophilic bioactive molecules, such as proteins, peptides, or nucleic acids, in oil-based formulations.

Fig.1

Classification of micelles based on structure. (a) Regular micelles. (b) Reverse micelles.6

Fig.1

Classification of micelles based on structure. (a) Regular micelles. (b) Reverse micelles.6

How do micelles work?

Derived from diverse materials including block copolymers (e.g., PEG-b-PLA), natural proteins (gelatin, casein, albumin), or hybrids (polymer-lipid, metal-integrated), micelles boast low CMC (10-6–10-7 M for polymeric types) for stability in blood, evading the reticuloendothelial system (RES) to prolong circulation. The hydrophobic core of micelles allows solubilizing poorly water-soluble drugs (paclitaxel, doxorubicin, etc.) while the shell can be modified with a variety of functional groups for specific targeting (folic acid, antibodies, etc.). In addition, stimulus-responsive micelles have been designed to respond to various environmental changes in tumour tissues (pH, GSH, enzymes, etc. ).

Classification of Micelles

Micelles, as core–shell nanostructures self-assembled from amphiphilic molecules, exhibit diverse classifications that directly dictate their functionality in targeted drug delivery (Table 1 & Table 2). The classification enables researchers to match micelle types to specific therapeutic needs—from solubilizing hydrophobic drugs to responding to tumour microenvironment cues. Therefore, understanding these categories is crucial for the development of micelle-based targeted delivery approaches, as each category offers distinct strategies for enhancing drug bioavailability, minimizing off-target toxicity, and promoting site-specific accumulation. In this context, two frequently employed classification methods were listed as follows:

Classification of Micelles Based on Composition

Micelles can be composed of surfactants, copolymers, or lipids. Based on different compositions, micelles can be categorized into three types: surfactant, polymeric, and lipid-based micelles. Each of them is used in specific applications due to the distinctive characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1 Classification of micelles based on composition.

| Category | Description | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surfactant Micelles | Formed by low-molecular-weight amphiphiles such as SDS or CTAB. | Simple molecular surfactants; form above CMC; dynamic and reversible structures. | Detergents, solubilization of hydrophobic compounds, analytical chemistry. |

| Polymeric Micelles | Formed from amphiphilic block copolymers (e.g., PEG–PLA, PEG–PCL, PEG–PPO). | High thermodynamic stability, low CMC, tunable core–shell morphology. | Drug and gene delivery, diagnostic imaging, and nanomedicine. |

| Lipid-Based Micelles | Composed of phospholipids or bile salts, often mimicking biological membranes. | Biocompatible, membrane-like structures; support encapsulation of lipophilic molecules. | Oral delivery, lipid digestion studies, and bioavailability enhancement. |

Classification of Micelles Based on Size

Conventional Micelles are composed of small-molecule surfactants (e.g., SDS, CTAB) and have a size range of 1-10 nm in diameter. Currently, nanomicelles are widely used in biomedicine for their enhanced in vivo stability and versatility in drug loading. They are commonly composed of amphiphilic block copolymers and have a size range of 10-100 nm in diameter. Moreover, to satisfy greater loading and controlled release requirements, supramolecular aggregates are used in the biomedical field. They are inherently aggregated micellar complexes, and their size is typically over 100 nm in diameter.

Table 2 Classification of micelles based on size.

| Category | Description | Typical Composition | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Micelles | 1–10 nm in diameter | Small-molecule surfactants (e.g., SDS, CTAB) | Simple, dynamic structures. | Used in detergency, solubilization, and analytical chemistry. |

| Nanomicelles | 10–100 nm in diameter | Amphiphilic block copolymers (e.g., PEG–PLA, PEG–PCL) | High stability, low CMC. | Ideal for drug encapsulation, targeted delivery, and imaging. |

| Supramolecular Aggregates | >100 nm in diameter | Aggregated micellar or vesicular structures | Larger, more complex organizations. | Applied in sustained release, gene delivery, and hybrid nanocarriers. |

Why Micelles for Targeted Delivery?

1. Core-shell structure enabling solubilization and circulation

As mentioned before, micelles have a hydrophobic core that can efficiently encapsulate poorly water-soluble drugs (e.g., paclitaxel, doxorubicin), while the hydrophilic shell (e.g., PEG, polysaccharides) enhances aqueous solubility. This shell can also help them evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES), thus prolonging the blood circulation of therapeutic drugs. Compared with surfactant micelles, polymeric micelles (e.g., PEG-PLA) have longer circulation times, thereby exhibiting enhanced tumour targeting ability.

2. Optimal size and structural stability

With a diameter range of 10–100 nm, micelles can penetrate through leaky tumour vasculature (which has pores larger than 400 nm) without causing embolism. Additionally, as polymeric micelles have a low Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC, ranging from 10-7 to 10-6M), their structure can be maintained in the bloodstream even after dilution, thus preventing premature drug leakage.

3. Biocompatibility and modifiability

As micelles are made from natural polymers (e.g., casein, gelatin, silk), they are biodegradable and non-toxic. Therefore, micelles have reduced immunogenicity. In addition, as their surface can be modified with ligands (such as folate or antibodies), drug-loaded micelles can specifically target tumour cells. For example, to improve delivery precision, casein micelles conjugated with specific ligands have been used for targeted delivery in breast cancer.

4. Stimuli responsiveness for selective drug release:

Micelles can be designed to respond to cues in the tumour microenvironment (TME). For example, pH-sensitive micelles (e.g., those with protonable amine groups) can be triggered to destabilize and release drugs in response to the acidic TME (pH 6.0–6.8, compared to 7.4 in normal tissues). Redox-sensitive or enzyme-sensitive micelles can be activated to release drugs in response to high intracellular glutathione levels or overexpressed enzymes (like matrix metalloproteinases). Stimuli responsiveness enables the release of drugs at target sites, resulting in reduced off-site toxicity.

Biomedical Applications of Micelles

By leveraging the core-shell structure, stimuli responsiveness, and biocompatibility, micelles are widely applied in many aspects of biomedical fields, with key applications spanning oncology, infectious diseases, biologics/nucleic acids, and photodynamic therapy.

Oncology

In oncology, micelles are applied to address chemo limitations. Their hydrophobic core can encapsulate poorly soluble drugs (e.g., paclitaxel, doxorubicin), and hydrophilic shells (e.g., PEG) can help evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES) for prolonged circulation. Additionally, stimulus responsiveness (acidic TME, high GSH) enables controlled drug release, leading to enhanced drug efficacy and reduced off-target toxicity. A typical example is paclitaxel-loaded PEG-PLA micelles, which have been shown to exhibit reduced cardiotoxicity and enhanced passive tumour targeting compared to free drugs.

Infectious disease

For infectious diseases, micelles can combat pathogens while lowering off-target toxicity. They can stabilize ARV combinations (DRV: EFV: RTV) by encapsulating antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin, clarithromycin) or antiretrovirals (e.g., efavirenz) to enhance their solubility and oral bioavailability. Additionally, micelles with antimicrobial peptides can target bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori, thus reducing mucosal irritation.

Biologics & nucleic acids

In the micelle-based delivery, micelles can protect fragile cargo. For instance, polyion complex (PIC) micelles can interact with anionic biologics (such as siRNA and proteins) via electrostatic interactions, thereby protecting them from nucleases and enabling targeted gene silencing. In protein delivery (e.g., insulin, antibodies), albumin or silk fibroin micelles can be used to enhance the drug bioactivity and intestinal absorption.

Photodynamic therapy

For photodynamic therapy (PDT), micelles can co-deliver photosensitizers (e.g., methylene blue) and chemotherapeutic drugs. By modifying with phenylboronic acid (PBA), keratin micelles can target tumour sialic acid, while co-delivered photosensitizers can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon exposure to light. Then, the generated ROS can trigger micelle disassembly, thus releasing chemo drugs (e.g., paclitaxel) for synergistic tumour killing.

Smart Micelles for Micelle-Based Targeted Delivery Strategy

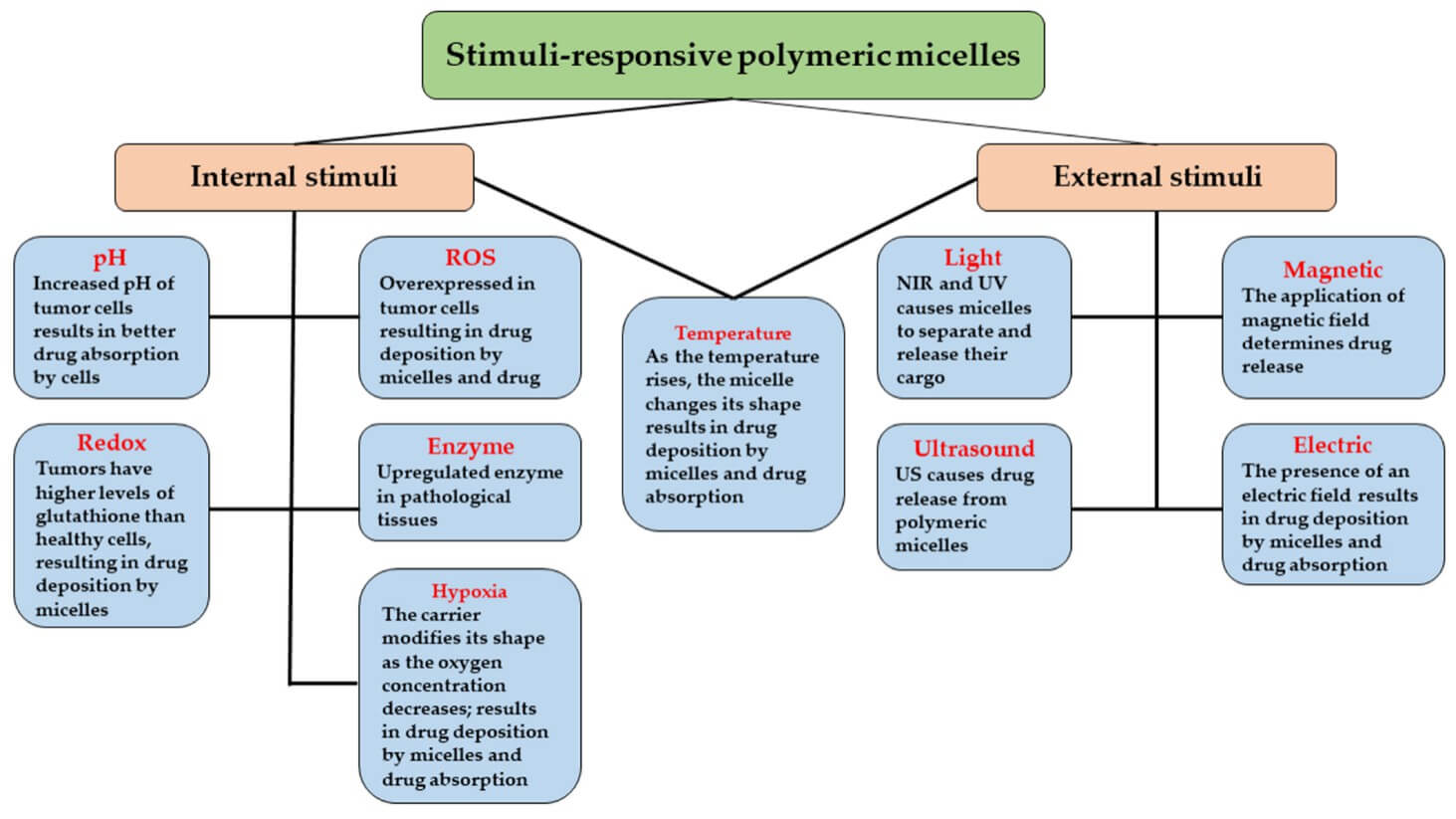

Except for modification with specific ligands, the stimuli responsiveness can be incorporated to endow micelles with active targeting ability to address the challenge of off-target drug release. As Figure 2 shows, there are many types of stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles.

Fig.

2 Different types of stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles.4

Fig.

2 Different types of stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles.4

1. pH-responsive for tumour microenvironments

As the tumour microenvironment has a lower pH value than normal tissues, pH-responsive micelles can be triggered to release drugs in acidic tumour tissue or endosomes by harnessing the acid-cleavable linkers or pH-sensitive blocks. So far, various pH-responsive polymeric micellar systems have been employed for the treatment and management of different types of cancers.

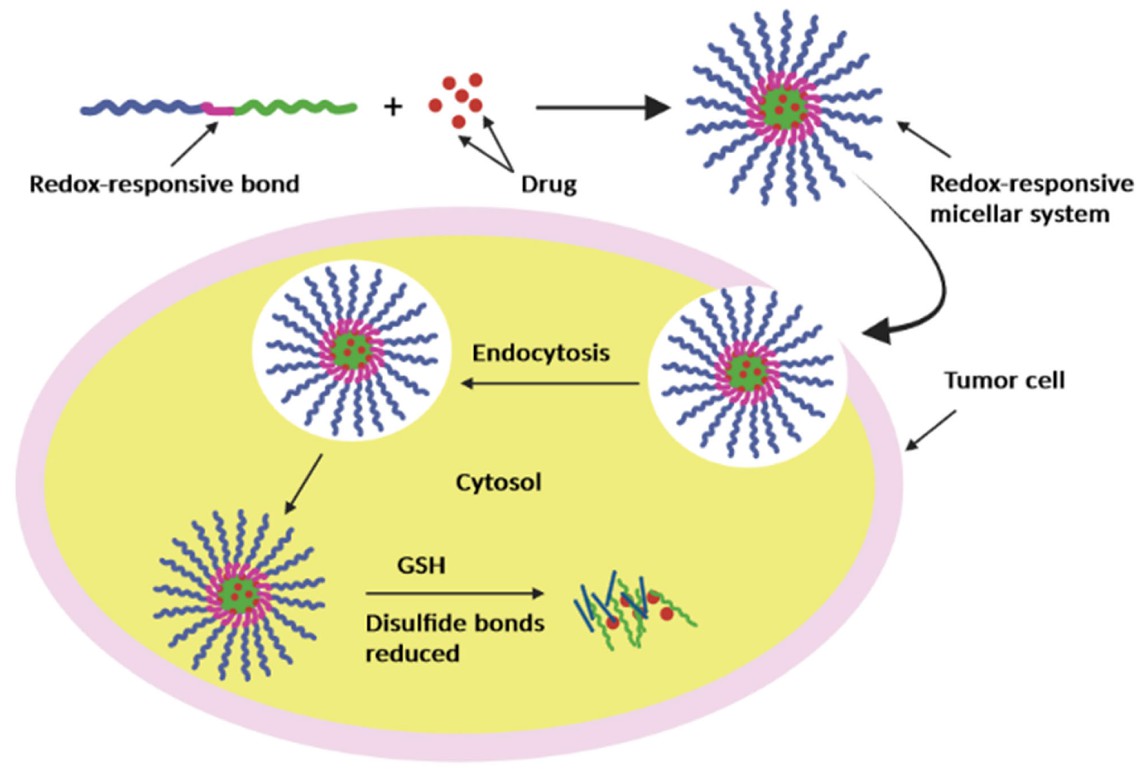

2. ROS/enzymes-responsive for inflamed tissues

Redox/Enzyme-Responsive Micelles can release drugs at tumours by responding to tumour-specific high glutathione (GSH) levels or overexpressed enzymes (MMP-2, trypsin) in tumour cells. For example, keratin-PEG micelles with disulfide linkages can release DOX in high GSH environments (Figure 3), and casein-N-isopropylacrylamide micelles can respond to trypsin (overexpressed in tumours) for enzyme-triggered drug release.

Fig.

3 Redox‐responsive micelle.4

Fig.

3 Redox‐responsive micelle.4

3. Co-delivery (drug+drug; drug+gene; drug+imaging)

Except for the incorporation of stimulus responsiveness, micelles can co-encapsulate agents to achieve synergistic drug efficacy. They can also carry imaging probes for theranostic use.

Micelles vs. Other Nanocarriers

As there are many drug delivery systems available, it is necessary to compare their characteristics for better application (Table 3). Compared to liposomes, micelles excel for hydrophobic drugs, rapid assembly, and flexible polymer chemistry. Compared with polymeric nanoparticles (polymeric NPs), micelles offer simpler self-assembly and easy chemistry tuning.

Table 3 The comparison of micelles with other nanocarriers.

| Carrier | Best For | Pros | Watch-outs | Typical Size / Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micelles | Poorly soluble small molecules; combos | Simple assembly; responsive release; tunable ligands | Stability vs. serum; leakage | 10–100 nm/moderate |

| Liposomes | Hydrophilic or amphipathic drugs | Clinically proven; bilayer versatility | Process complexity; shelf stability | 50–200 nm/variable |

| Polymeric NPs | Controlled solid matrices | Strong mechanical stability | More complex fabrication | 50–200 nm/moderate |

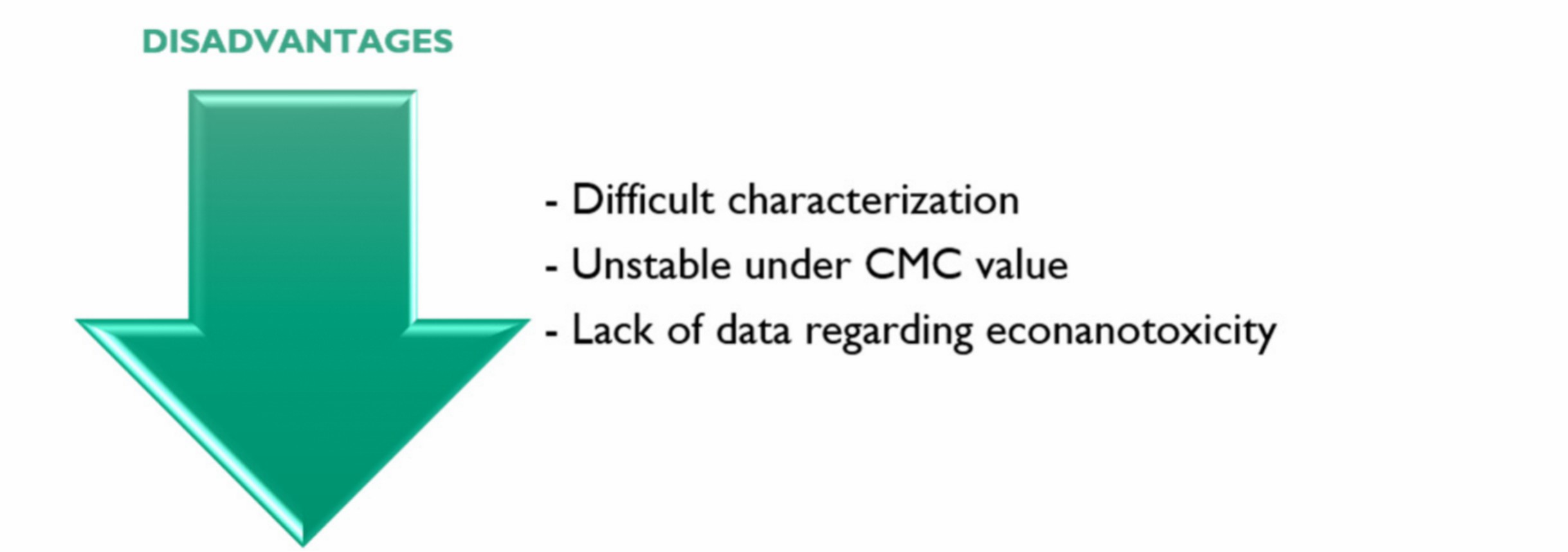

Challenges and Future Perspectives in Micelle-Based Delivery

Several key challenges exist in micelle-based targeted delivery, including a low critical micelle concentration (CMC), poor characterization of micelle-biological environment interactions, complex and scalable manufacturing, and unclear risks associated with nanotoxicity/econanotoxicity risks (Figure 4). To address these issues, the focus on CMC must be improved in the future by optimizing for stability, developing standardized characterization methods, scaling up the process by Quality by Design approaches, and providing long-term safety data. In addition, increasing indications in anti-ageing and fungal infections will likely unlock their further therapeutic potential in dermatology.

Fig.

4 Disadvantages of micelle-based delivery systems.2

Fig.

4 Disadvantages of micelle-based delivery systems.2

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What is a micelle in drug delivery?

It is a tiny, self-assembled particle with a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell. It carries water-insoluble drugs and maintains their stability in the bloodstream.

Why do micelles help in cancer therapy?

They can gather at tumours because of their size and the EPR effect. This helps raise local drug levels and can reduce side effects.

What are common polymers for polymeric micelles?

Shells often use PEG or PEO. Cores can use PLA, PCL, or related hydrophobic blocks that fit the drug.

Can micelles carry biologics or combinations?

Yes. With careful chemistry, micelles can co-deliver small molecules, peptides, nucleic acids, or imaging agents.

References

- Wang, Q., Atluri, K., Tiwari, A. K. & Babu, R. J. "Exploring the Application of Micellar Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Nanomedicine." Pharmaceuticals 16, 433 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/16/3/433.

- Parra, A., Jarak, I., Santos, A., Veiga, F. & Figueiras, A. "Polymeric Micelles: A Promising Pathway for Dermal Drug Delivery." Materials 14, 7278 (2021). https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/14/23/7278. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Nie, Y., Fu, G. & Leng, Y. "Nuclear Delivery of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems by Nuclear Localization Signals." Cells 12, 1637 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/12/12/1637.

- Negut, I. & Bita, B. "Polymeric Micellar Systems—A Special Emphasis on "Smart" Drug Delivery." Pharmaceutics 15, 976 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/15/3/976.Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Mustafai, A., Zubair, M., Hussain, A. & Ullah, A. "Recent Progress in Proteins-Based Micelles as Drug Delivery Carriers." Polymers 15, 836 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/15/4/836.

- Li, L., Zeng, Y., Chen, M. & Liu, G. "Application of Nanomicelles in Enhancing Bioavailability and Biological Efficacy of Bioactive Nutrients." Polymers 14, 3278 (2022). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/16/3278. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Janik, M., Hanula, M., Khachatryan, K. & Khachatryan, G. "Nano-/Microcapsules, Liposomes, and Micelles in Polysaccharide Carriers: Applications in Food Technology." Applied Sciences 13, 11610 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/21/11610.

- Hanafy, N., El-Kemary, M. & Leporatti, S. "Micelles Structure Development as a Strategy to Improve Smart Cancer Therapy." Cancers 10, 238 (2018). https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/10/7/238.

- Bose, A., Roy Burman, D., Sikdar, B. & Patra, P. "Nanomicelles: Types, properties and applications in drug delivery." IET Nanobiotechnology 15, 19–27 (2021). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1049/nbt2.12018.