Polymeric Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Strategies: Definition and Mechanisms

Boosting the solubility of poorly soluble drugs, facilitating controlled and site-specific release, and resolving many of the disadvantages of classic drug formulations, polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) have found wide-ranging use in modern drug delivery systems. In this piece, Creative Biolabs will introduce you to the basic concepts, main mechanisms, and common knowledge of PNP-based delivery.

Introduction to Polymeric Nanoparticles

What Are Polymeric Nanoparticles?

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are nanocarriers (1–1000 nm) made of natural or synthetic polymers for drug delivery to improve drug solubility, bioavailability, and targeting ability compared with traditional drug systems. As with all other nanocarriers, the polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) properties are dependent on their composition. For instance, natural polymers like chitosan (animal-derived), alginate (algae-derived), and albumin (protein) can provide inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability to the composed PNPs.

In contrast, synthetic polymers, such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), can equip composed PNPs with tunable stability, mechanical strength, and controlled degradation. Additionally, because polymers can be engineered, PNPs can be formulated to be sensitive to different stimuli (tumour pH, body temperature, enzyme levels, etc.) and thus release drugs in response to these physiological cues, which can lead to increased targeting specificity. In addition, "stealth" variants (e.g. PEGylated PNPs) can be conjugated to the surface of PNPs through these polymers, thus evading immune clearance. It is the combination of these advantageous properties that has not only led PNPs to be an integral part of modern nanomedicine but also made them useful in various industrial fields, including electronics, sustainable packaging, and agriculture.

Why Polymeric Nanoparticles Are Revolutionising Drug Delivery?

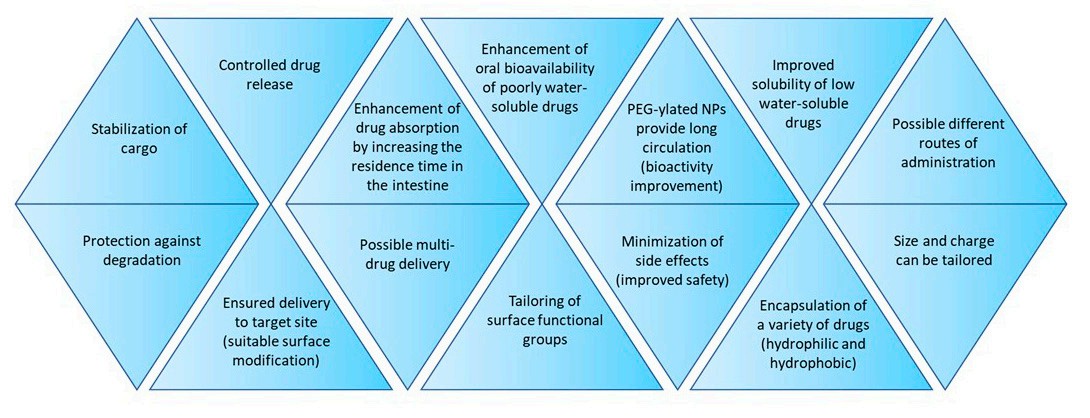

As Figure 1 shows, drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) offer multiple critical advantages over conventional crystalline active agents, addressing key limitations of traditional drug formulations. These advantages can be summarised as follows:

1. Enhanced Drug Stability and Protection

Conventional crystalline drugs are prone to degradation in physiological environments (e.g., gastrointestinal acids, blood enzymes) or during storage. PNPs can address this challenge by encapsulating or dispersing drugs within polymeric matrices (nanospheres) or polymeric shells (nanocapsules), thereby preventing the loss of drug efficacy.

Examples:

Chitosan PNPs can prevent drug breakdown in stomach acid and prolong drug residence in the intestines. Therefore, it is used for the delivery of oral drugs.

2. Improved Solubility and Bioavailability

Poor water solubility is the main reason for the low dissolution rates and bioavailability of conventional crystalline drugs. By leveraging their hydrophobic polymeric cores (e.g., PCL, PLGA) and hydrophilic polymer surfaces (e.g., chitosan, PEGylated PLGA), PNPs can solubilize poorly water-soluble (Class II) drugs and enhance their bioavailability.

Examples:

In cancer treatment, albumin-bound PNPs are used to enhance the solubility and oral bioavailability of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., paclitaxel).

3. Controlled and Targeted Drug Release

Burst release ("dose dumping", rapid release of the drug payload upon administration) with a short therapeutic window is a common drawback for most conventional crystalline drugs because they have uncontrolled drug release kinetics. This necessitates frequent dosing of conventional crystalline drugs, which can cause increased systemic toxicity and poor patient compliance. Therefore, to attain minimal off-target effects with prolonged therapeutic action, PNPs follow either a sustained release (extended and gradual release over a period of hours to weeks) or stimuli-responsive release (release is triggered only in target microenvironments) strategy. Additionally, PNPs can enhance their targeting specificity through an active targeting pathway by conjugating specific ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, or small molecules) to their polymeric surface. As a result, the drug-loaded PNPs' exposure to healthy tissues is reduced and systemic toxicity is diminished.

Examples:

In cancer treatment, PNPs are modified with folate to target folate receptor-positive cancer cells. pH-responsive PNPs are applied to release drugs specifically in the acidic microenvironment of tumour tissues (pH 5.5–6.5, which is lower than the normal physiological pH of 7.4). In the diabetic treatment, slow-degrading synthetic polymers (e.g., poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL)) are used to fabricate PNPs for long-term release of insulin.

4. Reduced Toxicity and Improved Safety

Conventional crystalline drugs often cause systemic toxicity due to non-specific distribution. In comparison, PNPs can mitigate the systemic effects by using biocompatible or biodegradable polymers. In addition, by enhancing targeting and bioavailability, PNPs can reduce the total drug dose required for therapeutic efficacy, thereby minimizing side effects.

Examples:

In terms of the components of polymeric nanoparticles, natural polymers (e.g., albumin, gelatin) have low immunogenicity, and synthetic PLGA can degrade into non-toxic lactic/glycolic acid. Moreover, carboplatin-loaded folate-grafted PNPs exhibit superior anticancer efficacy at lower doses with reduced side effects, compared to free crystalline carboplatin.

5. Versatility for Diverse Therapeutics and Delivery Routes

Conventional crystalline formulations are limited by the drug type (e.g., poor solubility for hydrophobic drugs, instability for proteins) and delivery routes (e.g., oral formulations often fail for acid-sensitive medications). To overcome these limitations, PNPs offer broad versatility in drug loading and delivery routes. They can encapsulate diverse therapeutics, including small molecules (such as paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil), proteins (like insulin and albumin), and nucleic acids (such as siRNA). By improving the drug resistance, PNPs can be applied for oral, intravenous, ocular, and nose-to-brain drug delivery.

PNPs offer broad versatility:

Examples:

PNPs can encapsulate a diverse range of therapeutics, including small molecules (such as paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil), proteins (such as insulin and albumin), and nucleic acids (such as siRNA). They can also co-deliver chemotherapeutics and immunotherapeutics (e.g., docetaxel + perifosine). By improving the drug resistance, PNPs support multiple delivery routes, including oral, intravenous, ocular, and nose-to-brain drug delivery.

Fig.1

Advantages of using drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles.1

Fig.1

Advantages of using drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles.1

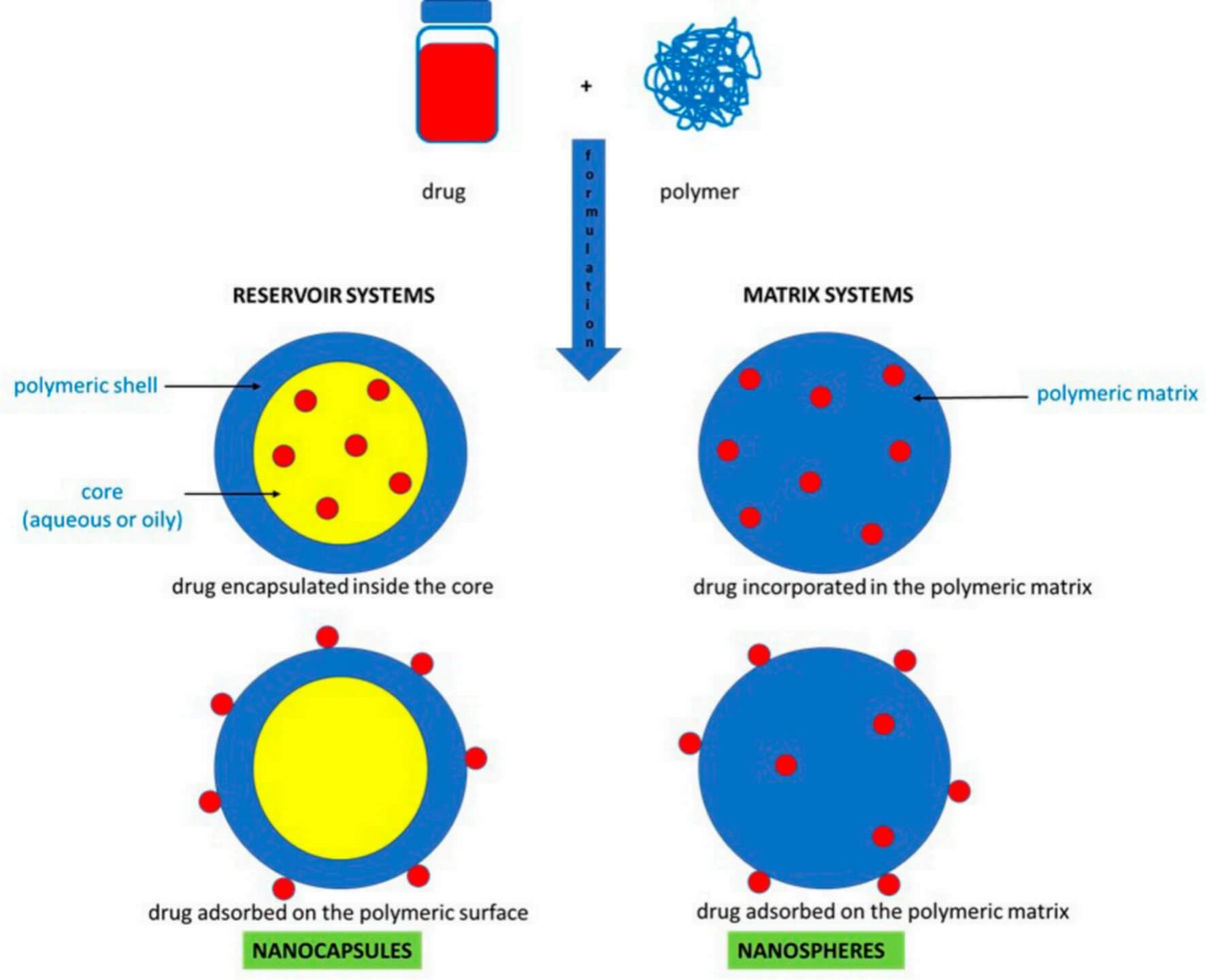

Types of Polymeric Nanoparticles: Nanospheres vs. Nanocapsules

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are primarily categorized into two core structural types: nanospheres and nanocapsules (Figure 2). Each of them is distinguished by its localization of drugs, arrangement of polymers, and suitability for drug delivery.

Nanocapsules

Nanocapsules are structurally characterized by a core-shell architecture. Drugs are encapsulated in the aqueous or oily core, which is surrounded by a thin polymeric shell. This structure allows for the protection of sensitive drugs (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids) from physiological degradation. For instance, curcumin-loaded poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanocapsules can shield the hydrophobic drugs from GI acid breakdown during oral delivery, leading to enhanced drug bioavailability. Moreover, the polymer composition (e.g., chitosan for mucoadhesion, PLGA for controlled degradation) of the shells can be tailored to optimize targeting or barrier penetration, prolonging drug residence on a specific location.

Nanospheres

Nanospheres are characterized as a matrix structure, where therapeutic agents (small molecules, proteins, or nucleic acids) are either dispersed uniformly within the polymeric network or adsorbed onto the particle surface. Their polymer matrices are made from either natural (e.g., chitosan, albumin) or synthetic (e.g., PLGA, PCL) polymers, allowing for steady drug release via polymer degradation or diffusion. A typical example is the 5-fluorouracil-loaded PLGA nanospheres, which can provide controllable release to avoid burst effects in colorectal cancer therapy.

Fig.2

Types of PNPs based on the composition.1

Fig.2

Types of PNPs based on the composition.1

Mechanisms of Polymeric Nanoparticle-Based Delivery

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) achieve effective drug delivery through three interconnected mechanisms. These mechanisms all address key limitations of conventional formulations.

Encapsulation and Protection

As mentioned before, PNPs (nanospheres or nanocapsules) can encapsulate drugs in polymeric matrices or shells, shielding sensitive therapeutics (e.g., insulin, nucleic acids) from physiological degradation, such as gastrointestinal acids or blood enzymes.

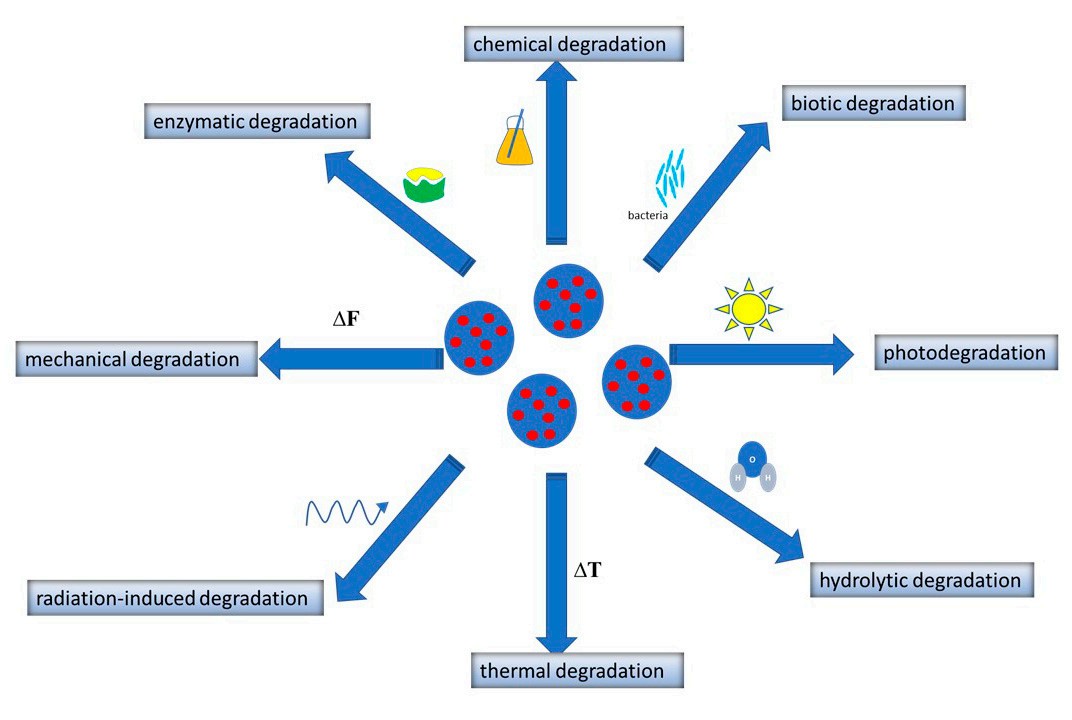

Controlled Release

The therapeutic kinetics of drugs are optimized via controlled release regulations, which are primarily driven by the properties of the polymer. Sustained release is driven by polymer degradation (Figure 3) or diffusion. For example, slow-degrading PCL can be used for long-term insulin delivery, thereby reducing the frequency of injections. Stimuli-responsive release is driven by the degradation of stimuli-responsive polymers (Figure 3). It avoids off-target burst release by ensuring that drugs are released only in diseased microenvironments (e.g., pH-sensitive chitosan PNPs in acidic tumours).

Fig.3

Mechanisms of PNP degradations.1

Fig.3

Mechanisms of PNP degradations.1

Targeted Delivery

Passive targeting leverages the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect to accumulate in tumours; active targeting utilizes ligand conjugation (e.g., folate for cancer cell receptors) to bind specifically to diseased cells. These mechanisms collectively optimize bioavailability and minimize toxicity.

Synthesis and Fabrication Techniques for PNPs

Producing polymeric nanoparticles requires precision and control. Common synthesis methods include:

Emulsification: Mixing polymers and drugs in an organic solvent, followed by solvent evaporation to form nanoparticles.

Droplet Microfluidics: Using micro-scale channels to produce uniform nanoparticles with high reproducibility.

Solvent Evaporation: Dissolving the polymer and drug in a solvent, then removing the solvent to create solid nanoparticles.

Polymerization: Forming nanoparticles directly from monomer precursors.

These techniques can be fine-tuned to control particle size, drug loading, and surface charge—all essential for optimizing targeted delivery efficiency.

Industrial and Biomedical Applications of PNPs

Besides the pharmaceutical sector, polymeric nanoparticles can be applied in various aspects of the industrial sector (Table 1).

Table 1: Industrial and Biomedical Applications of PNPs.

| Application Area | Mechanisms | Specific examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | Enable targeted/sustained drug delivery by encapsulating therapeutics in polymeric matrices. |

- Folate-conjugated PLGA PNPs target cancer cells for carboplatin delivery; - Chitosan PNPs load rotigotine for nose-to-brain delivery in Parkinson's treatment. |

| Electronics | Act as functional components for miniaturized devices. |

- Polymeric nanoparticle-based nanosensors detect temperature/humidity in portable electronics with

high sensitivity; - Conductive polymer nanoparticles form inks for flexible circuit printing. |

| Sustainable Packaging | Serve as biodegradable alternatives to conventional plastics. | - Cornstarch-based polymeric nanoparticles make water-soluble packing peanuts that dissolve without toxic waste, replacing non-biodegradable styrofoam. |

| Agriculture | Realize controlled pesticide release. | - Polydopamine-modified mesoporous polymeric nanobottles can load kresoxim-methyl, sustaining release for 336 h and improving foliar retention. |

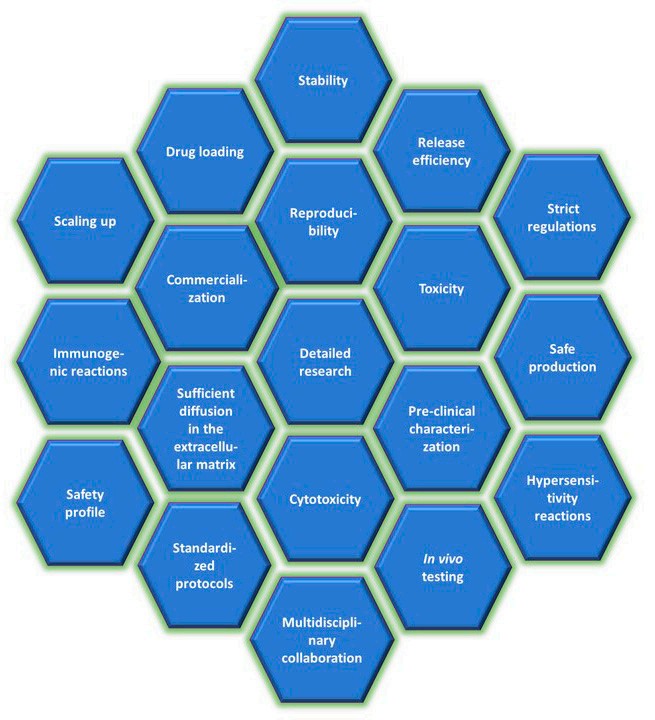

Challenges and Future Directions

While polymeric nanoparticles offer enormous potential as carriers in drug delivery systems, many challenges exist in the biomedical application of PNPs (Figure 4). These challenges can be summarised into four parts.

Scalability: Producing consistent nanoparticles in large quantities is a complex process.

Stability: Maintaining uniform particle size and drug loading is critical.

Regulatory Barriers: Ensuring safety, efficacy, and reproducibility for clinical translation.

Cost: High manufacturing and purification expenses.

Researchers are working toward standardized synthesis protocols, AI-driven optimization, and eco-friendly production to address these barriers.

Fig.4

Challenges in the PNP biomedical application.1

Fig.4

Challenges in the PNP biomedical application.1

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What are polymeric nanoparticles?

They are tiny polymer-based carriers (1–1000 nm) used for encapsulating and delivering drugs safely and efficiently.

How do polymeric nanoparticles work in targeted drug delivery?

They transport drugs directly to diseased tissues, enabling controlled release and minimizing side effects.

What are the main types of polymeric nanoparticles?

Nanospheres and nanocapsules differ in structure and drug distribution.

What challenges does the industry face?

Scalability, cost, stability, and regulatory compliance remain key challenges for large-scale use.

Conclusion

Polymeric nanoparticle-based delivery strategies represent a transformative leap in targeted therapeutics. From controlled release in cancer therapy to biodegradable alternatives in sustainable packaging, polymeric nanoparticles are shaping the future of both biomedical and industrial areas.

References

- Geszke-Moritz, M. & Moritz, M. "Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Comprehensive Overview, Perspectives and Challenges." Polymers 16, 2536 (2024). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/16/17/2536. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Park, S., Lu, G.-L., Zheng, Y.-C., Davison, E. K. & Li, Y. "Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Strategies for Combating Drug Resistance in Cancer Therapeutics." Cancers 17, 2628 (2025) .https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/17/16/2628.

- Eltaib, L. "Polymeric Nanoparticles in Targeted Drug Delivery: Unveiling the Impact of Polymer Characterization and Fabrication." Polymers 17, 833 (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/17/7/833.

Created in October 2025