Virus-Like Particles in Targeted Delivery: What Works, What's Next & How to Get There

Virus-like particles in targeted delivery provide genome-free protein shells that mimic viral entry to move drugs and editors into the right cells. With rapid retargeting, receptor-guided uptake, and re-dosable dosing, VLPs bridge the gap between AAV and LNP for precision delivery. This guide explains practical design choices and how Creative Biolabs helps you engineer, validate, and scale VLP programs.

What are VLPs in targeted delivery?

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are non-infectious, self-assembling nanoparticles derived from viral capsid proteins. As they lack genomes and replicases, VLPs possess high safety while mimicking native virus structure, size, and symmetry. Their unique properties make them ideal for vaccine and targeted delivery (e.g., gene-editing agents for cancer/genetic disorders) (Table 1).

Table 1 Unique properties of virus-like particles in targeted delivery.

| Property Category | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Safety | - Non-infectious, as VLPs lack viral genomes and replicases |

| Uniformity | - Highly homogeneous (unlike polymer/liposomal nanoparticles) |

| Immunogenicity | - Have strong immunogenicity, which is beneficial for vaccines |

| Cargo Encapsulation | - Versatile in cargo types: Small-molecule drugs, siRNA, ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), proteins |

| - Versatile in methods: Covalent (cysteine/lysine conjugation) or noncovalent (electrostatic, aptamer-mediated) | |

| Surface Engineering | - Flexible modification via genetic fusion or "click" chemistry |

| Targeting Ability | - Ligands (antibodies, transferrin) enable binding to specific cell receptors, thus reducing off-target accumulation |

| Delivery Advantages | - Combining viral transduction efficiency with nonviral transient cargo release to reduce off-target risks |

How VLPs achieve targeting

VLPs achieve targeting via precise surface engineering and ligand display. Ligands such as antibodies, transferrin, or RGD peptides were added to their surface via genetic fusion (e.g., inserting targeting peptides into HBVc or HPV L1 capsids) or chemical conjugation (cysteine-maleimide, lysine-NHS reactions, "click" chemistry). These ligands then bind specific cell receptors, guiding VLPs to target cells/tissues, reducing off-target delivery.

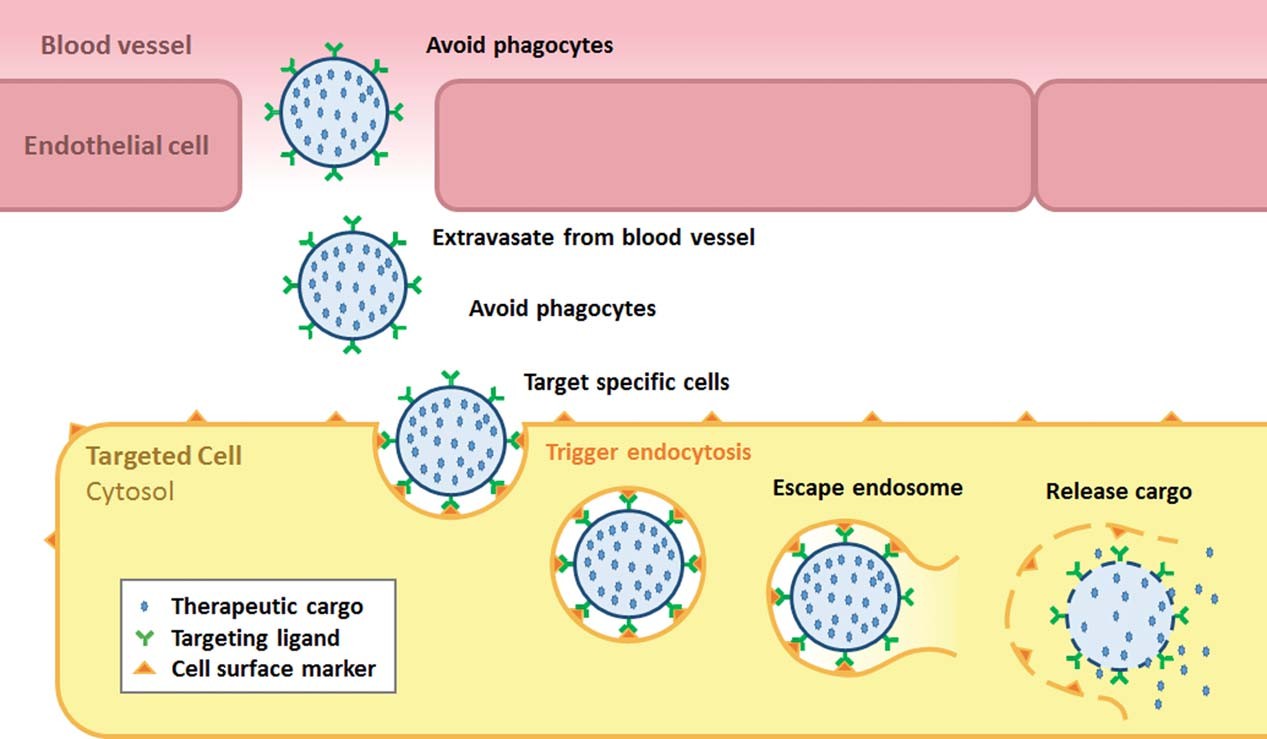

After receptor binding, cells internalize VLPs via clathrin or caveolin-mediated endocytosis (Figure 1). To avoid endosomal acidification degrading cargo, pH-cleavable linkers or proton-sponge domains are added to disrupt endosomal membranes.

v5 engineered virus-like particles (eVLPs) further optimize capsid mutations to boost endosomal escape capabilities. This enhancement ensures the effective intracellular delivery of cargo such as gene-editing ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), successfully converting initial receptor binding into the functional release of the cargo inside target cells.

Fig.1

The mechanism of VLP-based targeted delivery.3

Fig.1

The mechanism of VLP-based targeted delivery.3

VLP vs. AAV vs. LNP

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the VLP characteristics as a carrier in the targeted delivery, VLP is compared with AAV and LNP. From Table 2, it can be seen that VLP, AAV, and LNP differ sharply in safety, drug efficacy, cargo capacity, retargeting speed, tissue targeting, and manufacturing complexity. Their distinct attributes enable them to be utilized in various applications. To know how to choose fr your own program, you could visit the section "Buyer's guide: is a VLP the right choice for your program?" in this article.

Table 2 Comparison of VLP with AAV and LNP.

| Attribute | VLP | AAV | LNP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome integration risk | None (RNP/RNA only) | Low–moderate (DNA exposure; integration concerns are monitored) | None |

| Re-dosable | Generally yes (manage anti-capsid IgG) | Often limited by anti-AAV immunity | Often yes |

| Cargo sweet spot | Proteins/RNPs, enzymes, small RNAs | DNA ≤ ~4.7 kb | mRNA/siRNA; large nucleic acids |

| Retargeting speed | Fast (swap display ligand) | Slower (capsid engineering) | Slower (formulation+ligand work) |

| Typical efficiency | Rising; now AAV-like in some models | High in many tissues | High for hepatocytes; variable elsewhere |

| Manufacturing complexity | Medium; multi-host options | High; complex analytics | Medium; scalable chemistry |

For more information about these three delivery systems, please visit Creative Biolabs' Solutions: https://www.creative-biolabs.com/targeted-delivery/solutions.htm.

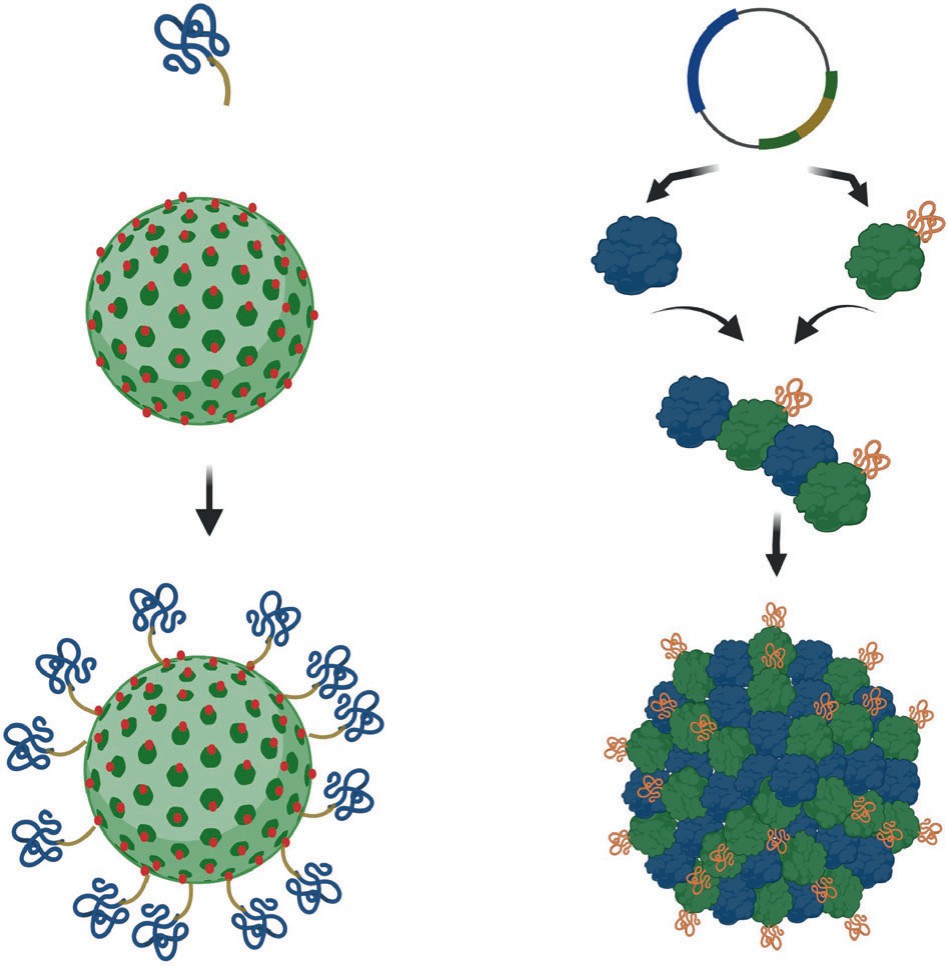

Functionalization routes: genetic vs. chemical

Genetic display (fusion or loop insertion)

This method inserts ligands into capsid genes (HBc, HPV L1), ensuring uniform display and avoiding post-assembly disruption. As it is simple and stoichiometric for short peptides or small domains, this functionalization route is ideal for tiny and stable ligands (e.g., tetanus toxin epitopes on CuMV-VLPs).

Orthogonal chemistries

As chemical methods (cysteine-maleimide, "click" chemistry) are good at preserving ligand activity and enabling precise ligand density tuning for targeted delivery, it is suitable for big, sensitive ligands or when post-assembly control is needed.

Decision rule

If the ligand is tiny and stable → genetic.

If the ligand is big, sensitive, or you need post-assembly control → chemical.

For more information about the functionalization, please visit Creative Biolabs' Solutions website to make an inquiry with our experts.

Fig.

2 Techniques for ligand conjugation.2

Fig.

2 Techniques for ligand conjugation.2

Payloads & Loading strategies

Small molecules

They can be tethered to capsid interiors or displayed outside for proximity action.

Proteins and enzymes

They can load onto VLP via genetic fusion or high-affinity adapters.

CRISPR RNPs and prime editors (for genome engineering)

Because gene editing materials, such as prime editors, are delivered as protein–RNA complexes, exposure is transient and does not risk vector integration. Loading methods include disassembly–reassembly, pH-gradient methods, or in-cell encapsulation during assembly.

Applications: oncology, editing, and CNS

Oncology

VLPs decorated with tumor-binding ligands (e.g., folate on CPMV-VLPs, HER2-targeting peptides on AP205-VLPs) concentrate payloads at cancer sites, mirroring antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) logic but leveraging a nanoparticle chassis. They enable intracellular prodrug activation or enzyme delivery. For example, Qβ-VLPs can carry photodynamic therapy agents to kill melanoma cells.

Gene editing

Next-gen engineered VLPs can deliver gene editing materials in vivo. In mouse models, v3 PE-eVLPs corrected a 4-bp Mfrp deletion (15% efficiency) in rd6 retinas and Rpe65 mutations (7.2% efficiency) in rd12 mice, restoring protein expression and partial vision—all with transient cargo exposure to reduce off-target risks.

CNS access

Research groups are demonstrating programmable tropism and evolving capsids for better delivery; some systems report AAV-like efficacy and better performance than LNPs in specific settings. However, translation needs careful dose-finding and safety pharmacology to ensure targeted, non-toxic delivery.

The engineering levers that move the needle.

In targeted delivery, VLPs' performance is mainly shaped by four engineering levers, including size, surface charge, ligand density & spacing, and capside scaffold. Table 3 shows how you can tune these levers to get the desirable VLPs for your targeted delivery research.

Table 3 Designing parameters of virus-like particles.

| Lever | What you control | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Size (≈20-150 nm) | Control size via assembly conditions and capsid scaffolds (e.g., HBc, CCMV) | Balances circulation, tissue penetration, and uptake; aligns with tumor EPR windows when used for oncology. |

| Surface charge (ζ-potential) | Tune surface charge via buffers, PEG coatings, or protein composition | Tunes opsonization, macrophage uptake, and serum stability. |

| Ligand density & spacing | Adjust ligand density/spacing via genetic display or chemical conjugation | too little weakens avidity, too much risks hook effects, and proper spacing drives receptor clustering. |

| Capsid scaffold | Choose capsid scaffolds (Gag-based, TMV) based on cargo compatibility and manufacturability (bacterial, yeast, plant, HEK cell systems) | to ensure scalable, functional VLP production. |

Manufacturability of VLPs

Expression platforms include E. coli (HBc), yeast, plants, insect (Sf9/baculovirus), and HEK293. Each has trade-offs in yield, post-translational modifications, process economics, and downstream burden.

Release & characterization panels

- Identity (capsid, ligand, and cargo confirmation)

- Particle size/PDI and concentration

- Potency (cell binding, uptake, or functional readouts)

- Residual DNA (≤10 ng/dose; length ≈100-200 bp), endotoxin, residual host-cell proteins, sterility, and bioburden

Buyer's guide: Is a VLP the right choice for your program?

Choose a VLP-first path if:

- Your payload is a protein, enzyme, or RNP, and you want transient exposure.

- You need rapid retargeting to new receptors without re-engineering a full viral vector.

- Repeat dosing is part of the clinical plan.

Consider AAV or LNP when:

- You need stable DNA expression (AAV) or large mRNA payloads (LNP).

- Your indication already has gold-standard biodistribution with those platforms.

How Creative Biolabs accelerates VLP-based targeted delivery

At Creative Biolabs, we integrate ligand discovery, capsid engineering, and payload optimization into one workflow. We design, prototype, and test VLPs across relevant models, then translate the winning design into a scale-ready process with a clear release panel.

Our workflow

- Design: receptor mapping, ligand shortlist, capsid & chemistry picks

- Prototype: display density and spacing sweeps; payload loading screens

- Characterize: size/PDI, identity, binding, uptake, and potency

- In-vitro→in-vivo: targeting and functional efficacy

For more information, please visit Creative Biolabs' website (Targeting Module Development Services) to make an appointment with our experts.

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

Do virus-like particles replicate in the body?

No. VLPs lack viral genomes and therefore cannot replicate. They behave as genome-free carriers.

How are drugs or editors loaded into VLPs?

Common methods include disassembly-reassembly, pH-gradient loading, and in-cell encapsulation during assembly.

Are VLPs safer than AAV for genome editing?

They offer transient RNP delivery without integration, a safety advantage for many editing use cases; however, every program still needs nonclinical safety and biodistribution data.

Can VLPs reach the brain?

Programmable and evolved VLPs have shown AAV-like performance in animal models and have delivered editors to neural tissues; translation requires careful dose and safety studies.

What are the most challenging CMC hurdles?

Controlling residual DNA (≤10 ng/dose; ≈100-200 bp), minimizing impurities, and building robust identity/potency assays that reflect the final, ligand-bearing construct.

References

- An, M. et al. "Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo." Nat Biotechnol 42, 1526–1537 (2024). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-023-02078-y

- Mohsen, M. O. "Virus-like particle vaccinology, from bench to bedside." Molecular Immunology (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-022-00897-8 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Rohovie, M. J., Nagasawa, M. & Swartz, J. R. "Virus‐like particles: Next‐generation nanoparticles for targeted therapeutic delivery." Bioengineering & Transla Med 2, 43–57 (2017). https://aiche.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/btm2.10049 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Raguram, A., An, M., Chen, P. Z. & Liu, D. R. "Directed evolution of engineered virus-like particles with improved production and transduction efficiencies." Nat Biotechnol 43, 1635–1647 (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-024-02467-x