Active Targeting with Peptide Ligands: A Practical Guide

Active targeting with peptide ligands turns delivery from passive drift into receptor-guided precision. By pairing small, tunable peptides with overexpressed receptors, developers can boost on-target uptake and cut background. In this practical guide, Creative Biolabs will distill mechanisms, design rules, and KPIs of active targeting with peptide ligands.

Introduction: What Is Active Targeting with Peptide Ligands?

Simple Definition of Active Targeting with Peptide Ligands

Active targeting with peptide ligands is a precision strategy in nanoparticle (NP)-based drug delivery, where bioactive peptides (molecular weight <10 kDa) are conjugated to drug-loaded nanocarriers. These peptides specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on target cells (e.g., integrin αvβ3 on tumor endothelium, EGFR on epithelial cancer cells), guiding NPs to accumulate at disease sites and boosting cellular uptake—addressing the limitations of non-specific drug distribution.

Classified by function, key peptide types include tumor-homing peptides (e.g., RGD, CendR), cell-penetrating peptides (e.g., TAT, R8) that enhance barrier penetration, and receptor antagonists (e.g., E5 targeting CXCR4) with dual therapeutic and targeting roles (Table 1).

Table 1 Classification of Peptide Ligands by Function.

| Peptide Category | Functional Definition | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Homing Peptides | Peptides that specifically recognize receptors overexpressed on tumor cells/tissues, promoting NP accumulation and penetration in tumor sites. | - RGD/cRGD: Binds integrin αvβ3 (overexpressed in tumor endothelial cells). |

| - CendR/iRGD: Binds neuropilin-1 (regulates vascular permeability in tumors). | ||

| - GE11: Binds epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, overexpressed in epithelial tumors). | ||

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Peptides that enhance NP penetration through biological barriers (e.g., cell membranes, endosomal membranes) by promoting endocytosis and endosomal escape. | - TAT/R8: Binds negatively charged cell membranes via electrostatic interaction and mediates internalization. |

| - pHLIP: Responds to acidic environments to facilitate membrane translocation. | ||

| Receptor Antagonist Peptides | Peptides that act as antagonists to specific receptors (exerting therapeutic effects) while simultaneously guiding NPs to target cells via receptor binding (dual targeting/therapeutic roles). | - E5: Binds chemokine receptor CXCR4 (overexpressed in metastatic tumor cells) to inhibit metastasis and enhance NP targeting to CXCR4-positive cells. |

Advantages of Peptide Ligands

Active targeting differs sharply from passive targeting, which relies on the EPR effect (abnormal tumor vessel permeability) for NP accumulation. Passive targeting suffers from inconsistent efficacy across tumor types and subregions, while peptide-enabled active targeting improves specificity, reduces off-target toxicity, and enhances NP penetration into tissues. Though peptide ligands have lower binding affinity than antibodies, their small size, low immunogenicity, easy modification, and cost-effectiveness make them ideal ligands for clinical translation.

- For more information about active targeting with peptide ligands, please visit Creative Biolabs' Targeting Module (ligands, linkers, carriers): https://www.creative-biolabs.com/targeted-delivery/solutions.htm.

Mechanism: How Peptide Ligands Enable Precision Targeting

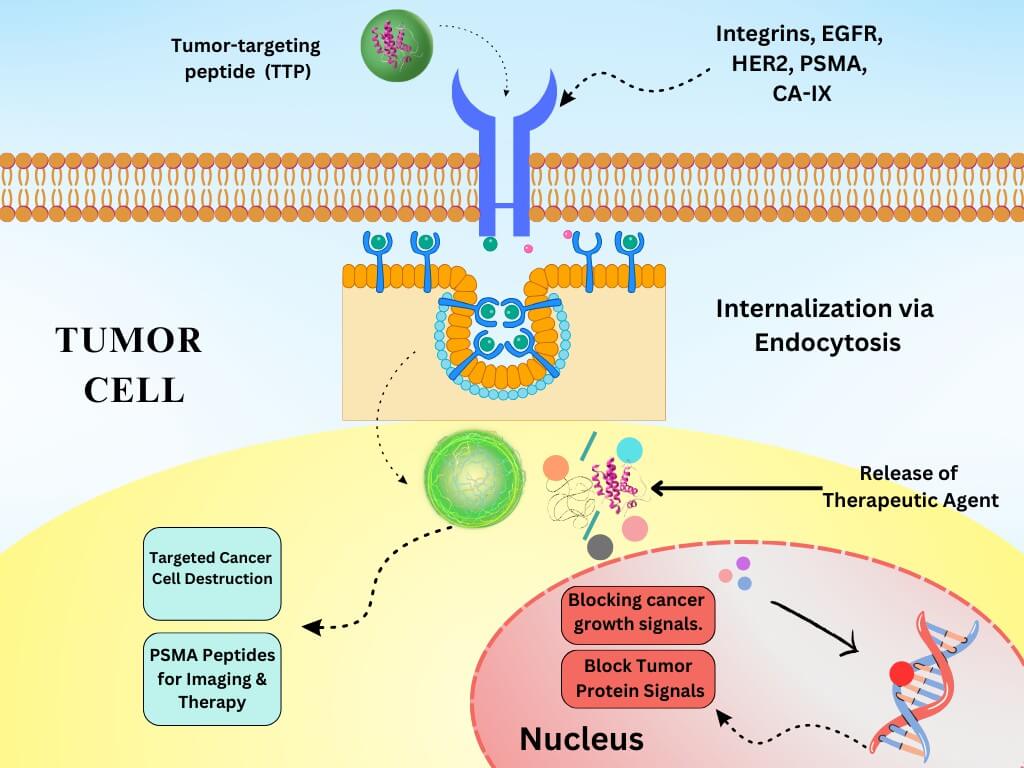

Peptide ligands achieve precision targeting mainly through three core mechanisms: receptor-mediated endocytosis, tumor microenvironment (TME) responsiveness, and multivalency and engineering optimization (Figure 1).

Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

Receptor-mediated endocytosis is key to the active targeting with peptide ligands. Peptide ligands bind to receptors overexpressed on tumor cells (e.g., RGD to integrin αvβ3, GE11 to EGFR), thereby triggering endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits (100-150 nm) or caveolae (60-80 nm). Acidification in endosomes/lysosomes or endosomal escape motifs (e.g., histidine-rich sequences) will then ensure payload release into the cytosol.

Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

Tumor microenvironment (TME) responsiveness can enhance specificity. Peptides use TME cues such as hypoxia (via 2-nitroimidazole linkers) or acidity (hydrazone/acetal linkers) to release payloads. For example, hypoxia-activated linkers are reduced by nitro-reductases in low-oxygen tumors, resulting in drug release.

Multivalency and Engineering Optimization

Multivalency and engineering optimization can boost drug efficacy via tuning of ligand density and modifications. Moderate ligand density (e.g., 0.25 mol% Myr-preS2-31 on liposomes) can avoid steric hindrance and maximize binding. Modifications such as D-amino acid incorporation or cyclization can enhance drug stability in the bloodstream.

Fig.1

Mechanism of peptide-mediated endocytosis.4

Fig.1

Mechanism of peptide-mediated endocytosis.4

Peptide Ligand Screening: Discovery Routes for Peptide Ligands

Peptide ligand screening relies on diverse, efficient routes to identify candidates with high specificity and high affinity for active targeting. Three key display technologies dominate the field of peptide ligand screening.

Phage Display

Phage display enables quick screening of large peptide libraries (often 109-1012 variants), making it widely used for discovering receptor binders (e.g., tumor-homing peptides targeting integrins or EGFR) due to its simplicity and scalability.

mRNA/ribosome Display

mRNA/ribosome display enables even larger library sizes. As it can bypass host cell limitations to isolate tight binders with sub-nanomolar affinity, mRNA/ribosome display is an essential method for targeting low-abundance receptors.

Yeast Display

Yeast display supports flow-sorting for affinity maturation and specificity tuning. Therefore, it is essential for optimizing ligands to avoid cross-reactivity with healthy cells.

Complementing experimental methods: Computational Design and Motif Mining

Computational design and motif mining can further speed up identification of the appropriate peptide ligand(s). Ranking of peptide motifs through in silico tools, prediction of binding hotspots, and in silico simulation of stability-enhancing modifications (e.g. cyclization, D-amino acid substitutions) prior to synthesis can minimize trial and error, and significantly decrease time/cost. These routes collectively ensure the efficient development of peptide ligands tailored for precise active targeting.

Design Rules that Drive Success

Successful peptide ligand design for active targeting relies on four core rules.

Target selection

Target receptor selection prioritizes receptors with high density on diseased cells (e.g., integrin αvβ3 on tumor endothelium, EGFR on epithelial cancer cells), low expression on healthy tissue, and efficient internalization—ensuring specific payload delivery.

Peptide format

Peptide format optimization balances functionality and ease of use:

- Linear peptides: enable quick testing and synthesis (ideal for initial screening);

- Cyclized peptides: boost protease resistance and binding affinity (e.g., cRGD for integrin αvβ3);

- D-amino acids or stapling: enhance stability;

- PEGylation: reduces rapid clearance when needed.

Ligand density

Too few ligands lower binding efficiency, and excess increases opsonization and immune clearance. Therefore, ligand density tuning is critical for making a balance between the avidity and stealth.

Stability

Stability engineering addresses serum proteases and shear forces. By leveraging cyclization, chemical modifications, or protective carriers (e.g., PLGA nanoparticles), in vivo peptide activity is preserved.

Choosing the Right Delivery Modality: Carrier-Conjugate Combinations

Selecting optimal delivery modalities for peptide ligands depends on cargo type, stability needs, and targeting goals.

Nanoparticles, liposomes, and micelles with peptide ligands

As nanoparticles, liposomes, and micelles excel at strong payload loading and in vivo stability, they are ideal for the delivery of small molecules (e.g., doxorubicin), RNAs (e.g., siRNA), or proteins.

Direct drug–peptide conjugates (ADC-like, but peptide-guided)

Peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) have the smallest footprint, enabling clean pharmacokinetics (PK) and focused targeting when cargo size is limited. Their direct peptide-drug linkage can avoid carrier-related clearance issues, making them suitable for cytotoxins or small-molecule payloads where minimal size drives tissue penetration.

Exosomes and native vesicles

Exosomes and native vesicles offer biocompatible native membranes for low immunogenicity but require consideration of scalability and rigorous analytics to ensure consistent peptide display.

What to Measure: KPIs and Benchmarks to Track

There are five KPI Benchmarks for active targeting with peptide ligands (Table 2).

Table 2 KPI Benchmarks for Active Targeting with Peptide Ligands.

| KPI | Typical target range | Why it matters | Assay method | Decision rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (affinity) | low nM–µM | Stronger binding can increase uptake | SPR/BLI | Balance affinity with off-rates |

| Internalization t½ | minutes–hours | Faster uptake improves exposure | Flow/cell imaging | Prefer fast internalizers |

| Receptor density | 104-106/cell | Higher density increases payload capture | Flow/quantitation kits | Prioritize high-density targets |

| Ligand density | app-specific | Tunes avidity vs stealth | Analytical chemistry | Optimize empirically |

| T/B ratio | >3:1 desirable | Confirms selective accumulation | In vivo imaging | Set a minimum for progress |

| Circulation t½ | app-specific | Affects exposure and EPR synergy | PK sampling | Match to delivery route |

Conclusion

Active targeting with peptide ligands gives your program a clear edge: specific binding, faster internalization, and cleaner biodistribution. Because ligands are small, tunable, and manufacturable, they integrate well with nanoparticles, liposomes, and drug–peptide conjugates. With well-chosen KPIs and assays, you can progress from discovery to in vivo validation with confidence.

Partner with Creative Biolabs to design, optimize, and validate your peptide-ligand strategy—from display-based discovery to carrier selection.

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What is active targeting with peptide ligands?

Active targeting with peptide ligands adds a receptor-specific peptide to a drug, nanoparticle, or imaging probe. The peptide drives selective binding and often internalization, which can raise local exposure while lowering background. Because the ligands are small and tunable, they fit a wide range of carriers and payloads.

Are peptide ligands better than antibodies for targeting?

Neither is always "better". Peptide ligands are small, often less immunogenic, and easy to synthesize and modify. Antibodies offer very high specificity and long half-life, but are larger and more complex.

How do I choose the right discovery platform?

The right discovery platform should be picked based on library size, speed, and downstream optimization. Phage display is fast and proven. mRNA/ribosome display can search extremely large spaces. Yeast display is excellent for affinity maturation with flow sorting.

How many ligands per nanoparticle is optimal?

It depends on particle size, receptor density, and stealth needs. Start with a moderate density, then adjust to balance avidity and clearance. Include controls and competition assays to confirm true targeting, not sticky surfaces.

Which assays prove active targeting works?

Use SPR/BLI for kinetics, flow, and confocal for binding and internalization, and in vivo imaging for biodistribution and target-to-background ratios.

How do peptide ligands affect biodistribution and clearance?

They can shift biodistribution toward the target tissue and away from non-target organs. At the same time, ligand properties and density influence circulation half-life. Therefore, measure PK and imaging together to guide tuning.

What are common failure modes, and how do we mitigate them?

Frequent issues include protease degradation, off-target binding, and rapid clearance. There are three ways to tackle these issues:

- Use cyclization, D-residues, and shielding to improve stability.

- Optimize density to raise avidity without harming stealth.

- Verify specificity with the proper controls.

References

- Liu, M., Fang, X., Yang, Y. & Wang, C. "Peptide-Enabled Targeted Delivery Systems for Therapeutic Applications." Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 701504 (2021). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2021.701504/full

- Yan, S., Na, J., Liu, X. & Wu, P. "Different Targeting Ligands-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Therapy." Pharmaceutics 16, 248 (2024). https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/16/2/248

- Yoo, J., Park, C., Yi, G., Lee, D. & Koo, H. "Active Targeting Strategies Using Biological Ligands for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems." Cancers 11, 640 (2019). https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/11/5/640

- Zaroon, Z., Mustafa, U., Hafsa, H., Aslam, S. & Bashir, H. "Recent Advancement, Mechanisms of Action and Applications of Tumor-Targeting Peptides." Biomed. Res. Ther. 12, 7602–7620 (2025). https://bmrat.org/index.php/BMRAT/article/view/996 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.