Active Targeting with Aptamer Ligands: A Practical Guide for Targeted Drug Delivery

Active targeting with aptamer ligands turns receptor biology into programmable precision for drug delivery. These compact DNA/RNA scaffolds fold into high-affinity 3D structures that bind overexpressed receptors and trigger receptor-mediated internalization—delivering tighter on-target exposure than passive EPR. With low immunogenicity and plug-and-play chemistry, aptamers power ApDCs, siRNA chimeras, and aptamer-decorated nanoparticles. At Creative Biolabs, we translate this strategy into practice—spanning SELEX design, stabilization, and conjugation—to drive measurable uptake and improved biodistribution.

Introduction: What Are Aptamer Ligands?

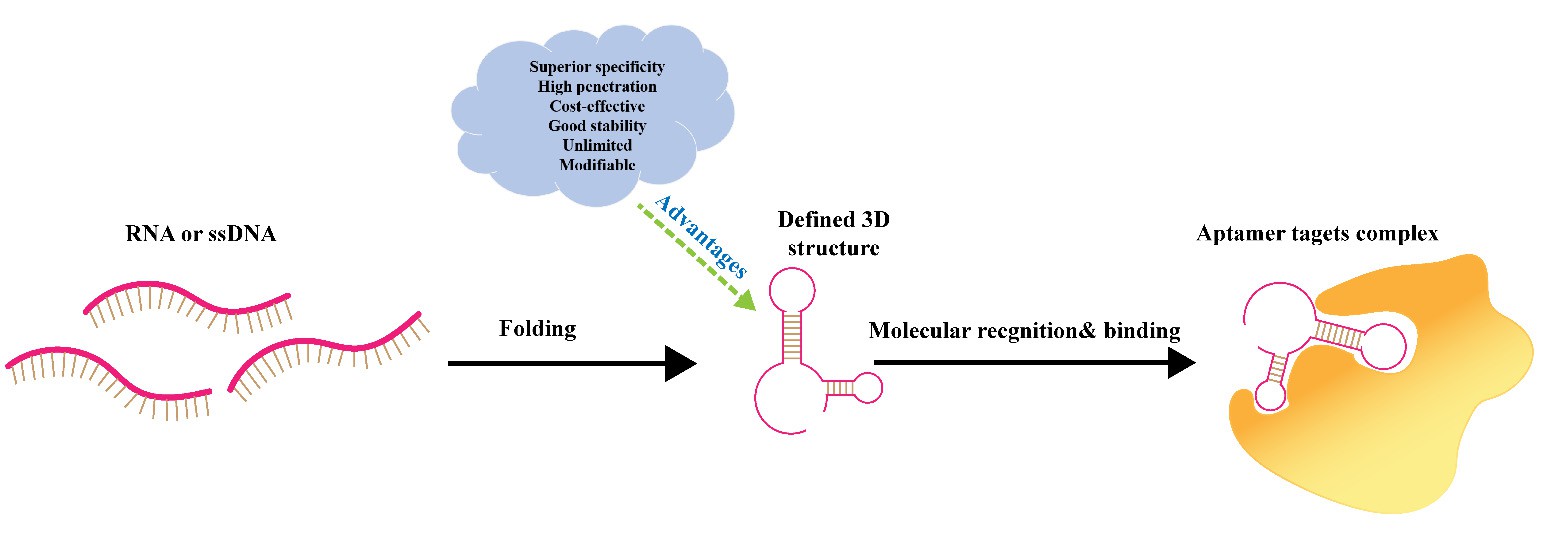

Aptamer ligands are short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into unique three-dimensional structures, enabling them to specifically recognize and bind to targets such as cell-surface proteins (e.g., EGFR, PSMA, or PTK7) —key for guiding targeted drug delivery (Figure 1). In contrast to larger ligands, the small size (molecular weight typically 8-25 kDa) and high programmability of small ligands allow them to efficiently direct drug carriers or therapeutics to specific cells that take up these particles through natural cell processes (e.g., endocytosis), leading to more controlled delivery of the cargo to the diseased site with lower off-target binding.

Fig.

1 Schematic view of the aptamer molecular recognition.2

Fig.

1 Schematic view of the aptamer molecular recognition.2

Common formats of aptamer ligands include:

- DNA or RNA variants (DNA offers better stability, while RNA aptamers can achieve enhanced binding affinity through chemical modifications);

- Monovalent designs (single binding unit) are suitable for simple targeting, while bivalent or multivalent structures enhance binding avidity—critical for targeting low-abundance biomarkers.

- Modified types (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-OMe, LNA, or Spiegelmers) that improve resistance to nucleases and extend in vivo half-life.

Derived via SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment)—a technique that "evolves" high-affinity aptamers against specific targets—aptamers can outperform some traditional ligands in batch-to-batch consistency and ease of synthesis.

For choosing between ligand classes beyond aptamers, please visit our service page: Targeting Module Selection System.

Aptamers vs Antibodies vs Peptides: Which Ligand Fits Your Use Case?

When designing active targeted drug delivery systems, choosing between aptamers, antibodies, and peptides hinges on balancing specificity, stability, and practicality—factors deeply tied to each ligand's inherent properties (Table 1). Aptamers, short single-stranded DNA/RNA with unique 3D conformations, stand out for their small size (8-25 kDa), which enables deep tissue penetration and facilitates easy chemical modification (e.g., 2'-F, 2'-OMe) to enhance nuclease resistance. In comparison, antibodies (150-180 kDa) face size-related tissue penetration limits and higher immunogenicity. Peptides, although small and easy to synthesize, often lack binding affinity and stability, and are prone to degradation by peptidases—an issue that aptamers can mitigate through structural tweaks.

Table 1 Comparison of aptamers with antibodies and peptides.

| Feature | Aptamers | Antibodies | Peptides |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approx. size | Very small; fast tissue penetration | Large; slower diffusion | Small-to-medium |

| Stability | Tunable via chemistry | Good; protein-based | Moderate; sequence-dependent |

| Production | Synthetic; scalable | Biologic; complex | Synthetic or recombinant |

| Conjugation flexibility | High; programmable sites | Good; needs careful chemistry | Good; many chemistries |

| Screening | In vitro SELEX | Animal-based or display | Library or rational design |

| Cost | Lower per variant | Higher | Lower-to-moderate |

Guidance box:

- When you need a small size, fast penetration, easy chemical control, and low immunogenicity. → Choose aptamers

- When long clinical precedent or Fc-mediated functions are critical. → Choose antibodies

- When you want a minimal size with simple sequences and known motifs. → Choose peptides

Biophysical Parameters: When Active Targeting with Aptamers Helps Most

Active targeting using aptamer ligands delivers maximum value in specific scenarios tied to biophysical and therapeutic needs. To improve active targeting, researchers can tune four biophysical parameters to achieve the optimal active targeting.

- It shines first when target cells have a high density of receptors (e.g., PSMA on prostate cancer cells, HER2 on breast cancer cells) and rapid receptor-mediated endocytosis. The latter prevents aptamers from getting trapped on cell surfaces and promotes the rapid internalization of the aptamer with its payload. This also obviates futile binding and increases intracellular drug accumulation.

- It is also critical when the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect is inconsistent (e.g., in poorly vascularized tumors or metastatic lesions). Here, aptamers provide a receptor-guided "pull" to direct carriers into target cells, thereby overcoming the limitations of the EPR effect.

- Additionally, active targeting with aptamers is ideal for potent payloads such as siRNA, small-molecule chemotherapeutics (e.g., doxorubicin), or radionuclides. Additionally, compared to non-targeted delivery, their high specificity can ensure tighter on-target exposure while minimizing toxicity to healthy tissue.

- Finally, it adds value when dual-target logic is planned: aptamers can be engineered to recognize two biomarkers (e.g., PTK7 on tumor cells and VEGF on tumor stroma), thereby reducing off-target uptake by restricting delivery to tissues where both targets coexist, and enabling the distinction of tumors from healthy tissue.

Designing Aptamer-Targeted Systems

Discovery & Selection

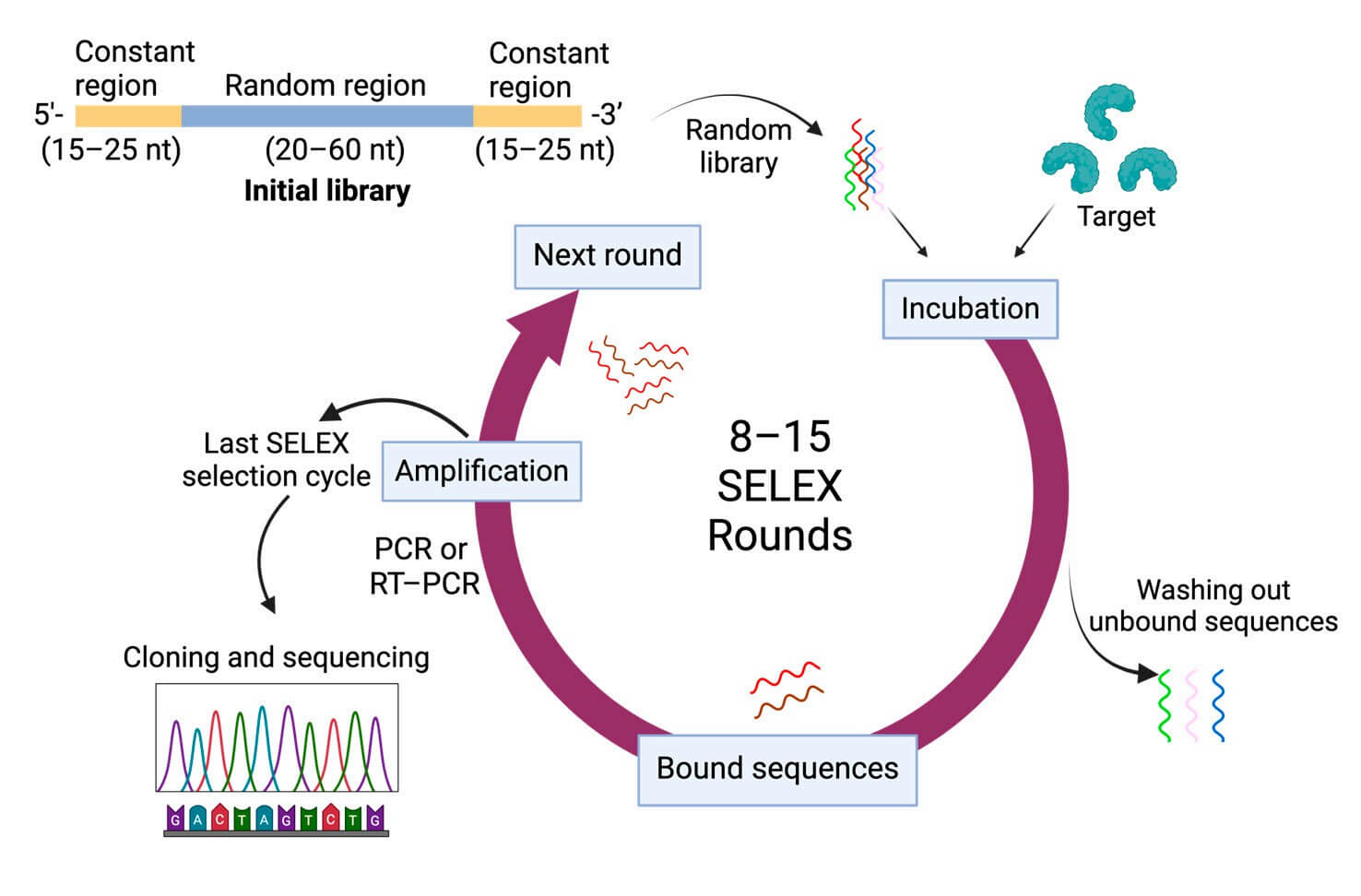

SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) works by iteratively selecting high-affinity aptamers from an extensive random DNA/RNA library. This process involves incubating the library with the target, isolating bound sequences, amplifying them, and repeating the process to enrich specific binders (Figure 2). Over the years, various SELEX variants have been developed to target different aspects, such as proteins, whole cells, or living organisms.

- Target-based SELEX utilizes purified proteins (e.g., EGFR, PSMA) to precisely control binding sites, ensuring aptamers recognize defined epitopes. This method is ideal for single well-defined biomarkers.

- Cell-SELEX utilizes live cells to preserve native receptor structures (e.g., PTK7 on leukemia cells), thereby avoiding artifacts associated with purified proteins. Therefore, this method is suitable for targeting functional cell-surface molecules.

- In vivo SELEX enriches aptamers that survive circulation and home to tissues (e.g., tumor microenvironments). It is primarily used to address discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo studies.

Fig.

2 General SELEX procedures.3

Fig.

2 General SELEX procedures.3

Chemical Stabilization

Chemical stabilization of aptamer ligands is a foundational step in enabling their practical use for active targeted drug delivery, as it directly addresses core in vivo challenges, including degradation by nucleases and rapid clearance by the kidneys, while safeguarding the specific target-binding ability.

- To shield aptamers from serum nucleases, modifications such as 2'-F, 2'-OMe, LNA, or phosphorothioate backbones can be added.

- To reduce rapid kidney clearance (a common issue for small aptamers), PEGylation (using 20-40 kDa PEG is typical) or other size-boosting strategies can be utilized to avoid filtration through renal pores.

- Over-modification, such as excessive PEGylation, can disrupt the aptamer's 3D structure, weakening its binding affinity to targets.

Conjugation Strategies

Conjugation strategies for aptamers are crucial to optimizing their targeted drug delivery, as they determine how effectively aptamers deliver payloads (small molecules, siRNA) or bind to nanocarriers while maintaining precise diseased cell targeting.

- For Aptamer–Drug Conjugates (ApDCs), small molecules (e.g., doxorubicin) are linked to aptomers via cleavable (acid-labile hydrazone) or stable linkers. Cleavable types release drugs in acidic tumor endosomes. Cleavable linkers, such as acid-labile hydrazone, can release drugs in the acidic endosomes of tumors.

- Aptamer–siRNA chimeras pair targeting aptamers (e.g., PSMA-binding) with siRNA strands. The aptamer guides the chimera to target cells, while siRNA silences cancer genes (e.g., Bcl2), avoiding off-target effects.

- For surface grafting to carriers (e.g., liposomes, PLGA nanoparticles, exosomes), aptamers are attached to the surface of the carriers. The aptamer density and surface orientation on the carrier surface should be optimized, as overloading aptamers will lead to steric hindrance and reduced binding specificity. 5–10 aptamers per liposome have been shown to work best.

Endosomal Escape Add-ons

To prevent payloads from being degraded or recycled out of cells, it is necessary to facilitate their exit from endosomes.

- pH-responsive linkers (which break down in acidic endosomal environments), ionizable lipids (that disrupt endosomal membranes to release their contents), and membrane-active peptides (such as TAT, which interacts with endosomal surfaces to facilitate escape) can be used to get aptamer-delivered payloads out of endosomes.

- Test intracellular release early: Use confocal microscopy paired with endosomal markers (such as LAMP1) to visually confirm payloads escape endosomes and reach their intended intracellular sites.

Platforms You Can Build Today

By leveraging aptamer ligands for active targeted drug delivery, three actionable platforms can be constructed, each rooted in the high specificity and adaptability of aptamers, with straightforward, step-by-step workflows.

Aptamer–Drug Conjugates (ApDCs)

ApDCs excel at simplifying delivery and avoiding linker instability. By embedding drugs within the aptamer's backbone, ApDCs eliminate problems associated with linkers while keeping the aptamer's ability to target (tumors or biomarkers) intact, specifically.

Workflow:

- Select a clinically validated nucleotide analog drug (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine) that matches the aptamer's nucleotide structure.

- Replace part or all natural nucleotides in the aptamer sequence with the drug analog during chemical synthesis—this preserves the aptamer's 3D structure and target-binding ability (e.g., to nucleolin or MUC1).

- Validate the conjugate's binding to the target biomarker and ensure drug release occurs at the tumor site (e.g., via nuclease degradation of the aptamer in the tumor microenvironment).

Aptamer-Functionalized Nanoparticles

Aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles enhance drug loading and tumor accumulation using accessible nanocarriers. The advantages of this platform include ample space for drug loading, stimulus-responsive drug release (e.g., activated by pH fluctuations or reactive oxygen species) tailored to the tumor microenvironment, and enhanced specificity.

Workflow:

- Choose a biomarker (e.g., EGFR, EpCAM).

- Use SELEX to get aptamers.

- Modify aptamers (add thiol/amine) and nanoparticles (e.g., MSNs, liposomes) for conjugation.

- Link aptamers via covalent/stimulus-sensitive linkers.

- Validate in vitro binding/uptake.

- Screen in vivo distribution.

Multivalent & Bispecific Aptamers

Multivalent and bispecific aptamers enhance affinity and target coverage. Multivalent aptamers amplify binding to overexpressed receptors; bispecific ones target heterogeneous tumors (e.g., MUC1 + CD44), thereby improving efficacy.

Workflow:

- Select a clinically validated nucleotide analog drug (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine) that matches the aptamer's nucleotide structure.

- Pick single (multivalent) or dual (bispecific) tumor targets.

- Isolate aptamers via SELEX.

- Modify for scaffolding.

- Link to scaffolds (DNA tetrahedron for multivalent, PEG for bispecific).

- Test dual binding/uptake, and screen biodistribution.

Biomedical Applications

Aptamer ligands power versatile active targeting solutions across key biomedical areas. They leverage many strengths, including high specificity, adaptability, and compatibility with diverse cargoes to address the unmet needs.

Oncology

In cancer, they allow targeted therapy for both prevalent and refractory tumours. For instance, aptamer-drug conjugates (ApDCs) can target nucleotide analogs (such as 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine) to tumour cells through nucleolin or MUC1 biomarkers and avoid systemic toxicity. Aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles (e.g., mesoporous silica, liposomes) can carry high loads of chemotherapeutics (e.g., doxorubicin) and release cargo in response to tumor microenvironment cues (e.g., pH, reactive oxygen species), thereby enhancing efficacy in triple-negative breast cancer and pancreatic cancer.

Rare diseases

For rare diseases, aptamers address the unique challenge of targeting small, specific cell populations. Compared with standard therapies, they enable targeted delivery of gene therapies or small-molecule drugs to cells with rare disease-specific markers (e.g., mutant proteins in rare hematologic disorders), resulting in minimized off-target effects.

Imaging and diagnostics

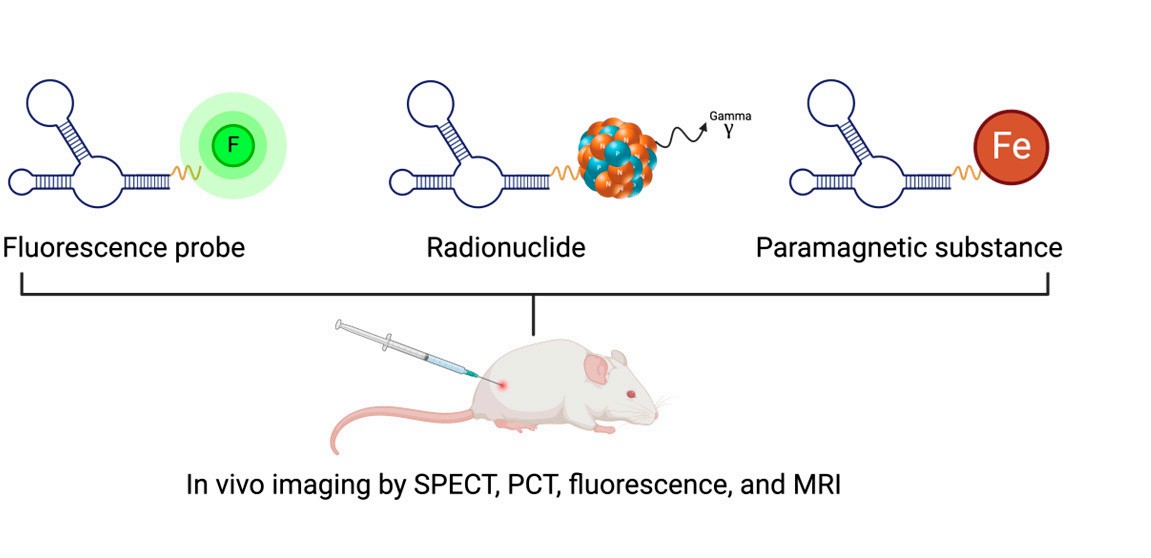

In imaging and diagnostics, aptamers elevate accuracy and enable early intervention. They are the active powerhouses behind a wide variety of in vivo imaging techniques, including, but not limited to, SPECT/PET imaging using aptamers labeled with radioactive isotopes (99mTc, 64Cu) to track tumor foci (aptamers that target EpCAM in colorectal cancer); high-resolution fluorescence imaging using fluorescent dyes linked to aptamers to image very small tumors or metastases; and aptamer-linked paramagnetic agents (e.g., gadolinium, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles) to enhance MRI contrast for imaging tumors that are located deep within tissue (Figure 3). Additionally, aptasensors can detect cancer biomarkers (e.g., CEA in gastrointestinal cancers, MPT64 in tuberculosis) in blood or urine with exceptional specificity, enabling rapid point-of-care testing to accelerate diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Fig.

3 Aptamer-based in vivo molecular imaging techniques.3

Fig.

3 Aptamer-based in vivo molecular imaging techniques.3

Challenges & Solutions

Active targeting with aptamer ligands faces key hurdles that can hinder delivery efficiency; however, chemical modification and design optimization can address these gaps. Table 2 presents five key challenges in the application of aptamer ligands, along with corresponding practical solutions. Rapid renal clearance (small size) can be eased via PEGylation, multimerization, or albumin conjugation to extend in vivo circulation. Nuclease degradation of unmodified aptamers can be solved by 2'-F/2'-OMe/LNA modifications or protective carriers. Off-target binding can be reduced via Counter-SELEX, competition assays, or dual-target aptamers. Endosomal trapping can be addressed with pH-responsive linkers, ionizable lipids, or endosome-active helpers. Variable receptor density can be managed through upfront profiling and adaptive ligand density to boost consistency.

Table 2 Risks and Solutions.

| Risk | Why it happens | How to mitigate |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid renal clearance | Small size clears fast | PEGylation, multimerization, albumin binders |

| Nuclease degradation | Unprotected nucleic acids | 2'-F/2'-OMe/LNA, protective carriers |

| Off-target binding | Similar receptors in healthy tissues | Counter-SELEX, competition assays, dual-target logic |

| Endosomal trapping | Limited escape after uptake | pH-responsive linkers, ionizable lipids, endosome-active helpers |

| Variable receptor density | Patient or tissue heterogeneity | Upfront receptor profiling, adaptive ligand density |

How Creative Biolabs Accelerates Aptamer Targeting

At Creative Biolabs, we integrate discovery, engineering, formulation, and analytics to rapidly move from concept to rigorous, data-driven results.

What we do

- Discovery: target assessment, SELEX (target/cell/in vivo), counter-selection design.

- Engineering: chemical modification matrix, linker chemistry, ligand density optimization.

- Formulation: liposome/polymer/exosome platforms with aptamer surfaces; tight control of size and PDI.

- Assays: binding/uptake/internalization, endosomal escape, biodistribution, and functional readouts.

- Deliverables: sequences, QC package, assay reports, and pilot batches aligned to your next milestone.

Internal link: Explore ligand options and pairing logic in our Targeting Module Development Services.

Related Services You May Be Interested in

FAQs

What is an aptamer, and how does it enable active targeting?

An aptamer is a short DNA or RNA strand that folds into a specific shape to recognize a target. By binding a cell-surface receptor, it guides the payload to the cell and supports receptor-mediated internalization.

How do aptamers compare to antibodies for delivery?

Aptamers are smaller, generally less immunogenic, and easier to modify chemically. Antibodies have long clinical precedent, but they are larger and more complex to produce.

Which payloads work best with aptamer targeting?

Small molecules, siRNA/ASO, proteins, and imaging agents work well. The key is matching the aptamer's receptor to a fast-internalizing pathway.

How do you improve stability and reduce clearance?

Use 2'-modifications and PEGylation or multimerization. Test nuclease stability and biodistribution early to tune size and circulation time.

What data do I need before animal studies?

Collect binding Kd, specificity against counters, internalization kinetics, serum stability, and initial biodistribution data to justify the in vivo plan.

References

- Li, Y. et al. "Aptamer nucleotide analog drug conjugates in the targeting therapy of cancers. Front." Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 1053984 (2022)." https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2022.1053984/full

- Wei, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, R., Wang, J. & Chen, Z. "Aptamers as Smart Ligands for Targeted Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy." Pharmaceutics 14, 2561 (2022). https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/14/12/2561 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Ye, Z., Chen, H., Weinans, H., Van Der Wal, B. & Rios, J. L. "Novel Aptamer Strategies in Combating Bacterial Infections: From Diagnostics to Therapeutics." Pharmaceutics 16, 1140 (2024).https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/16/9/1140 Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

- Yoo, J., Park, C., Yi, G., Lee, D. & Koo, H. "Active Targeting Strategies Using Biological Ligands for Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems." Cancers 11, 640 (2019). https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/11/5/640