shRNA in Infectious Diseases-Silencing Pathogens at the Source

Introduction of shRNA in Infectious Diseases

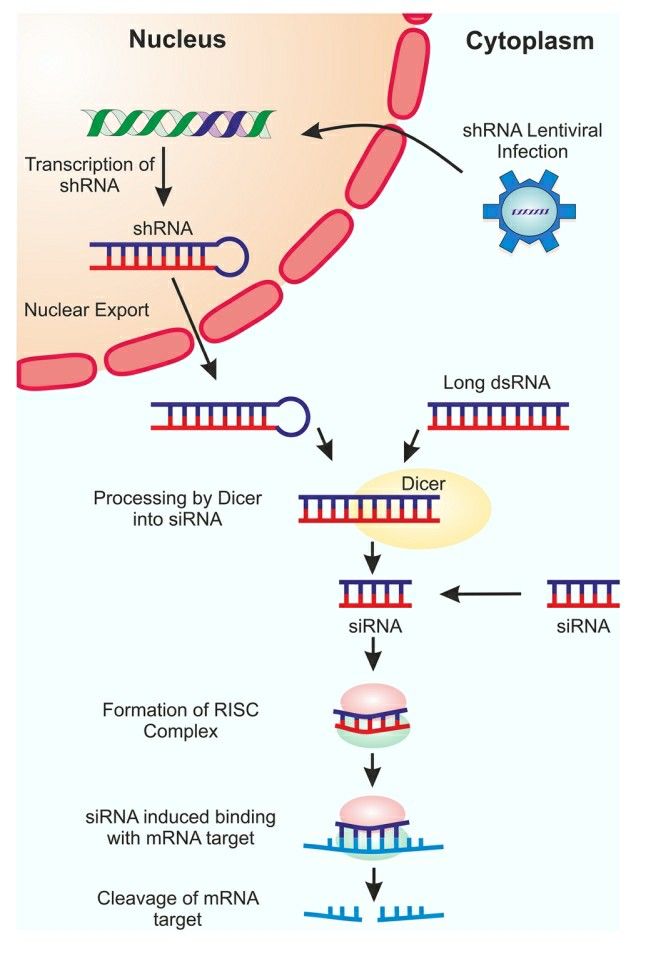

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) is a synthetic nucleic acid molecule, a class of RNA molecules that induce RNA interference (RNAi) and subsequent silencing of the target gene. shRNA is often transcribed from DNA and forms a hairpin structure. The shRNA is processed by Dicer to generate small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), the latter are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). In RISC, siRNAs direct shRNA to bind to and degrade the complementary mRNA to silence the target gene. Loading shRNA into RISC is 10 times more efficient than loading siRNA, which means less dose is needed to have a therapeutic effect while avoiding off-target effects. This makes shRNA a good candidate for treating infectious diseases where very precise and long-term regulation of gene expression is necessary.

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of RNAi silencing mechanism1,4.

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of RNAi silencing mechanism1,4.

The urgency of treatment for infectious diseases

Infectious diseases are a pernicious and significant public‐health challenge globally. Some diseases have been successfully eradicated from the environment, such as smallpox, while others, like poliomyelitis, are almost gone. However, there is a large group of diseases for which there is little or no hope of containment. Pathogens that are able to switch to infecting humans can sometimes be found where people and animals are in close contact. The new host, in this case a human, is often not as well adapted to these zoonotic infections as the original host. The previous outbreaks of avian influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), hantavirus, Nipah virus, and even the HIV epidemic have all been due to pathogens that normally inhabit animals, but which have been able to find a new, susceptible, human host. In addition, overuse and misuse of antibiotics is threatening even our ability to treat more common infections. We have a large number of bacterial species that are now resistant to even our most powerful antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics; similarly, the formerly first‐line drugs to fight malaria are now almost ineffective.

Key considerations in shRNA Design for application in Infectious Diseases

- Promoter selection

The starting point for the design of shRNA is selection of an expression cassette. As other gene products, shRNAs can be transcribed from any promoter available in commercially available expression vectors. However, as a non-coding molecule, special considerations have to be made to enable the transcript to fold correctly into the appropriate structure so that the miRNA biogenesis machinery can recognize and process it.

- Pol III promoters

"First generation" shRNA mimics pre-miRNA structure, which is a hairpin with 2-nt overhangs at the 3' end. Since shRNA transcripts must have well-defined sequence to fit this structure, one of the important considerations for shRNA is that the sequence must be well defined to fit such structure. Pol III promoters are able to transcribe the shRNA from a well-defined position (23 nt from the TATA box) and stop transcription inside a track of thymidines (T), making it perfect to express exact sequences of pre-miRNA-like shRNAs. In contrast, Pol II promoters come with a post-transcription processing (capping and polyA addition) that makes them incapable of such job. The first nucleotide of shRNA should match the transcription start site. One common mistake is leaving a gap between the two positions due to the insertion of cloning sites. This gap will create extra nucleotides on the 5' end of the intended hairpin structure, and therefore prevents shRNA from being recognized by Dicer, decreasing the efficiency of shRNA. Moreover, Pol III promoters usually prefer to start transcription with a purine. Therefore, the first nucleotide of Pol III-driven shRNAs should be either G or A. Otherwise, the transcription will start at another position near the optimal one, producing shRNAs with suboptimal structure.

- Pol II promoters

Pol II promoters are highly customizable in their expression levels of shRNA. shRNA may be transcribed from ubiquitous (e.g. CMV or SV40), tissue/cell-type specific (e.g. ALB, INS or Pdx-1), or inducible promoters. Poly-adenylylation of a transcript along with Pol II transcription disables the ability of the transcript to contain well-defined termini. Thus, it is not surprising that the pre-miRNA-like shRNAs transcribed by Pol II are not recognized by Dicer, and hence remain non-functional. Rather, the shRNA must be embedded in the structure of a primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) in order to be recognized and excised from the transcript by Drosha. Another feature of Pol II and pri-miRNA is the ability to express multiple shRNAs in one transcript. In fact, more than 40% of human miRNAs are grouped in clusters. However, the processing of miRNAs in a cluster is complicated, because the processivity of each miRNA/shRNA depends on and is influenced by other miRNAs/shRNAs in the cluster.

- Selection of target sequence

One of the most important steps in shRNA design is choosing the target sequence. It seems like a simple matter, as RNAi is well known for its "ability to target any sequence". Nevertheless, there are still some aspects that should be taken into account to make the designed shRNAs potent and specific.

- Base-pairing between guide strand and target

There are two critical conditions for this repression model: the level of complementarity between guide strand and target, and the identity of Ago. An efficient gene knockdown requires using the cleavage repression mechanism, which depends on Ago2 and near-perfect complementarity between the guide strand and the target. Positions 9 and 11 of the shRNA are especially important, since any disruption of duplex structure at this region will result in the loss of slicing activity. Although a large number of complementary nucleotides in both the 5' region and the middle region of the guide strand are critical for Ago2-mediated cleavage, pairing at the 3' end is not necessary. Indeed, mutations at position 18, 19, 20, 21, all of which promote dislocation and thus turnover rate of Ago2, help RISC work more efficiently for highly abundant targets. In addition, the ternary structure of Ago-guide-target suggests that the first nucleotide of the guide strand does not pair with the first nucleotide of the target mRNA, and that the 5' U placement in the guide is independent of target sequence.

- Localization of the target site

As miRNA binds to a single-stranded mRNA, in animals the miRNA target sites are most often located in the 3' untranslated region (3'UTR). Because the ribosome hinders the relatively weak binding between RISC and its target sequence in the coding region of mRNA, siRNA-induced RISC cleaves target mRNA in a transient manner. Therefore, it is much easier to design shRNAs to have perfect complementarity to any portion of the mRNA sequence. Furthermore, as many mRNAs from the same gene family share similar sequences, additional care is needed in choosing target sequence to ensure that it is specific to the gene of interest. In contrast, targeting a consensus sequence is a valid approach to repress expression from the whole gene family. Moreover, alternative splicing and polyA site selection result in mRNA isoforms. To achieve knockdown of gene expression from all isoforms, shRNA must target the sequences shared by all isoforms.

- Local structure of the target site

Because the RISC complex cannot unfold structured RNA, the target sequences must be located in a region of open structure where the RISC can begin to hybridize. However, once the initial interaction has occurred at the 5'-end region, the complementary base pairs at the 3'-end stabilize the interaction, and the RISC complex can disrupt any nearby secondary structures to allow further extension of the hybridization. Accessibility of target sites can be determined experimentally or estimated computationally based on minimum free energy of secondary structure which is often correlated with AU-richness of surrounding sequences. Furthermore, RNA binding proteins (e.g. HuR and DND1) bound to nearby sequences can affect the accessibility and mask the target site from RISC binding.

shRNA Applications in Viral Infections

The shRNAs are delivered to the nucleus by a plasmid or lentivirus and are integrated into the host DNA. Then, they are transcribed and accumulate slowly in the cytoplasm. As shRNA is not easily lost, expression of shRNA lasts longer than siRNA (> 10 days). But in some cases, cells may lose the plasmid and so expression of shRNAs could be terminated or may be silenced by negative epigenetic modification. Cells are thus cultured under selection for the shRNA phenotype. Most shRNA is used to confirm hits discovered by other methods. shRNA was performed on Bombyx mori embryonic cells to knockdown the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1). NPC1 was considered a potential baculovirus receptor because it interacts with Bombyx mori promoting protein (BMP) which increases baculovirus production. Two unique shRNAs were constructed to target the NCP1 gene and a 40% reduction in NCP1 expression was achieved which led to a considerable reduction in baculovirus infectivity. Co-immunoprecipitation data demonstrated receptor validation by showing interaction between NCP1 and the major baculovirus glycoprotein gp64. NCP1 was shown to be a putative receptor for Ebola virus by genetic knockout screening in haploid cells. Knockdown of NPC1 in human peripheral blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells by shRNA rendered them resistant to filovirus infection.

shRNA Applications in Bacterial Infections

- Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is an important cause of superficial skin infections, sepsis and pneumonia. S. aureus virulence factors include surface proteins, secreted toxins, and biofilm formation. This germ produces microbial surface components that recognize adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs), which mediate adhesion to host tissue and contribute to biofilm formation. Blocking the expression of surface proteins by shRNA like fibronectin-binding proteins and protein A can stop bacterial adhesion and biofilm creation which helps avoid infections. S. aureus produces proteases that break down host immune molecules and impair the host's ability to fight off infection. The host can better combat bacterial infections by silencing the genes via shRNA responsible for producing these proteases. Controlling bacterial gene activity related to biofilm formation through shRNA can help stop chronic infections like cystic fibrosis and chronic wounds by reducing both antibiotic resistance and immune system evasion.

- shRNA Targeting Biofilm Formation

The formation and maintenance of a biofilm by Pseudomonas aeruginosa are governed by multiple genes. Pseudomonas aeruginosa produce a polysaccharide called polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) through the ica operon to create biofilm. Biofilm formation suppression through shRNA targeting the ica operon will boost antibiotic effectiveness. Pseudomonas aeruginosa employs the quorum sensing (QS) system (las and rhl systems) to regulate the expression of biofilm associated genes and virulence factors. The application of shRNA to target QS genes will block biofilm maturation while decreasing bacterial virulence. Biofilms often harbor antibiotic-resistant bacteria which make them harder to treat. Disrupting antibiotic resistance genes such as efflux pumps or beta-lactamases with shRNA restores bacterial sensitivity to antibiotics which improves treatment success.

Future Directions

One of the most promising areas for the development of future shRNA therapy is to design safe and efficient delivery systems that will allow shRNA molecules to be delivered to target tissues and activate their action. Several reports have described the construction of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors expressing anti-tumor shRNAs both in vitro and in small animal models. One such example was the use of AAV expressing shRNAs against Hec1 (highly expressed in cancer). Repeated intra-tumoral administration caused anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on tumor cells. Another recent example used shRNA mediated down-regulation of the androgen receptor (AR). Systemic delivery of recombinant AAV vectors stably expressing shRNA against the AR gene eradicated prostate xenografts in nude mice. An upcoming clinical trial will involve the use of RNAi by ex vivo lentiviral vector delivery of an shRNA expression cassette into hematopoietic stem cells harvested from patients with HIV. These cells must be reinfused into these patients for in vivo therapeutic effects. One other potential avenue for the development of this field is the combined use of shRNA with current drugs. One example of this would be using shRNA targeting bacterial virulence factors to potentiate antibiotic effectiveness while minimizing the chance of resistance.

References

- Barrass, Sarah V., and Sarah J. Butcher. "Advances in high-throughput methods for the identification of virus receptors." Medical microbiology and immunology 209.3 (2020): 309-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-019-00653-2.

- Hong, Zhenyi, Nikola Tesic, and Xavier Bofill-De Ros. "Analysis of Processing, Post-Maturation, and By-Products of shRNA in Gene and Cell Therapy Applications." Methods and Protocols 8.2 (2025): 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8020038.

- Shi, Da, et al. "Significant interference with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus pandemic and classical strain replication in small-intestine epithelial cells using an shRNA expression vector." Vaccines 7.4 (2019): 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines7040173.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.