Application of Adeno-associated Viral Vectors in the Central Nervous System

Introduction of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors

Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) represent non-enveloped parvoviruses that are helper-dependent with an icosahedral capsid structure measuring approximately 25 nm in diameter. The AAV genome measures approximately 4.7 kb and includes ∼145 bp inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) at both its 5′ and 3′ ends. The natural version of AAV called wildtype AAV (wtAAV) contains a linear single stranded DNA genome with two open reading frames (ORFs). The open reading frames of AAV encode four replication proteins called Rep and three capsid proteins named Cap/VP together with an assembly activating protein known as AAP. wtAAV needs simultaneous infection with adenoviruses or herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) to replicate properly and produce viable AAV particles.

Three advancements have been instrumental in enabling the use of AAV as a recombinant vector for gene transfer applications: Successful creation of AAV vectors relies on the ability to employ natural or synthetic AAV capsids for pseudotyping together with the cloning and characterization of adenoviral helper genes needed for infectious AAV particle generation and the knowledge that ITRs serve as the exclusive cis-acting molecular signature required for transgene packaging in the AAV capsid. Streamlined components have become essential tools for creating recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors which incorporate diverse promoter elements and transgene cassettes for various gene transfer techniques. The scientific breakthroughs previously discussed enable us to produce AAV vectors with limited wildtype virion contamination.

Biology of AAV Cell Entry and Implications for Central Nervous System Gene Transfer

- The features of AAV

Multiple essential processes including cell surface receptor binding followed by endocytic uptake and endosomal escape must occur before nuclear entry and capsid uncoating to achieve genome release and transcription for successful AAV vector transduction. The regions of AAV capsids that face the external environment determine how they interact with host cell surfaces. Research has shown that many natural AAVs use cell surface glycans as their main receptors. Variations in glycan architecture have been identified as the cause for differences in gene transfer efficiency using AAV capsids across various organs. The AAV serotypes 1, 5, and 6 attach to N-linked sialic acid (SA) while AAV4 stands as the sole natural AAV isolate that attaches to O-linked SA moieties on mammalian cells. AAV2 along with AAV3 and AAV6 attach to heparan sulfate proteoglycans while AAV9 needs N-terminal galactose residues to achieve gene transfer. AAV2 vectors that attach to HS achieve predominantly neuronal transduction when directly injected into the central nervous system (CNS) while AAV1 and AAV5 vectors binding SA can transduce both neurons and some glial cells efficiently. Researchers discovered that AAV2's selective neuronal targeting corresponds with the higher presence of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on neurons compared to glial cells. HS binding not only supports the neurotropic preference of AAV2 but also limits the CNS regions accessible by AAV vectors.

- The effect of AAV

Researchers have discovered that the lysine amino acid at position 531 of the AAV6 capsid protein is essential for binding to heparan sulfate. Research with HS binding and non-binding variants of AAV1 (AAV1E531K) and AAV6 (AAV6K531E) revealed that HS binding negatively affects CNS transduction when AAVs are injected into the brain. The point mutation studies received support because safe doses of soluble heparin co-injected with AAV2 resulted in a significant elevation of CNS transduction levels. Among all available vectors for CNS gene transfer N-terminal galactose binding AAV9 stands out as one of the most efficient options. Research demonstrates that AAV9 achieves thorough transduction of neuronal and glial cells when injected through multiple routes in both small and large animal models. After entering the CNS, AAV vector-mediated gene transfer effectiveness depends on multiple factors such as post-entry cellular trafficking and genome-related events.

Direct AAV Administration Into the CNS

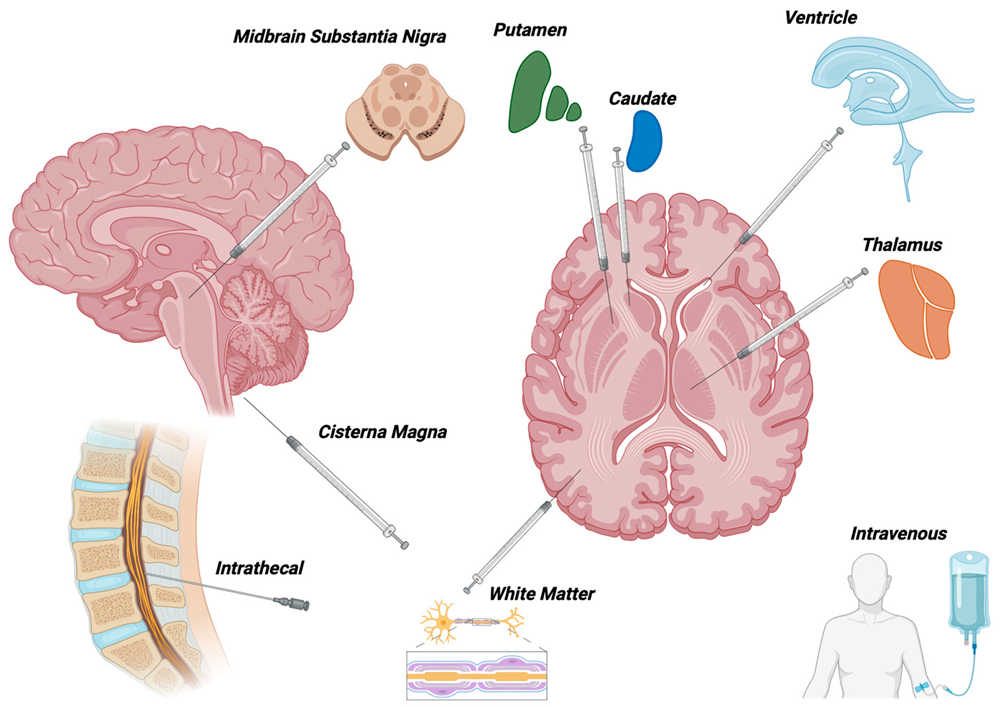

Researchers have implemented direct CNS AAV injections to attain high transgene expression levels in multiple animal models. Researchers use two main AAV vector administration techniques which include intra-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) administration along with intra-parenchymal administration. The CSF serves multiple purposes by supplying nutrients while directing stem cell migration through molecular and physical signals and eliminating interstitial solutes from brain tissue. The CSF resides in the subarachnoid space while also extending through cerebral ventricles, cisterna magna, foramena under the cerebellum and maintains direct contact with both spinal cord and brain tissue along the rostrocaudal axis.

- Intra-parenchymal administration

The delivery of reporter and therapeutic transgenes to extensive CNS regions has been effectively accomplished through AAV injections into cerebral ventricles, cisterna magna and intravertebral lumbar puncture. The serotypes AAV9 and rh.10 demonstrate an intrinsic proficiency for widespread distribution throughout brain parenchyma. Intra-CSF injections with these vectors have enabled researchers to deliver corrective transgenes across extensive regions of the CNS for long-term expression in spinal muscular atrophy and Krabbe disease models.

- Intra-cerebrospinal fluid administration

Certain AAV vectors demonstrate precise cell-selective transduction patterns when administered via intra-CSF injections. When researchers administer AAV4 through intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection they achieve selective astrocyte targeting specifically in the k zone area that borders the cerebral ventricles. Adult neural stem cells make up the ependyma and possess capabilities for permanent migration and differentiation which enables them to continually repopulate defined brain regions. Using AAV4 to deliver neurogenic factors such as noggin and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has demonstrated sustained recovery effects in mouse models of devastating CNS diseases like Huntington's disease. Scientists conducting in vivo research have also discovered unique structural characteristics and low similarity to other natural isolates through biophysical analysis of the AAV4 capsid.

Fig.1 Modes of delivery for AAV-mediated gene therapy to the nervous system used in clinical trials1,7.

Fig.1 Modes of delivery for AAV-mediated gene therapy to the nervous system used in clinical trials1,7.

- Intravenous administration of AAV Vectors for CNS Gene Transfer

A single dose of systemically delivered vectors enables complete gene transfer to the CNS throughout the body. The minimally invasive method of delivering intravenous (IV) injections enhances the clinical value of administering AAV vectors through the bloodstream. Two principal obstacles prevent us from employing this method for CNS therapeutic gene transfer. The initial significant issue during IV administration of AAV vectors arises because AAV vector particles spread widely into off-target organs including the liver spleen and kidneys. The administration of AAV9 through IV injections reaches neurons and glia in rodents and NHPs successfully but results in more than ten times higher viral genome accumulation in the liver and spleen than in the brain. The application of optimized AAV vector dosages alongside proper safety measures helps minimize systemic leakage and neutralizing antibody-mediated viral clearance. Blocking blood flow to peripheral organs such as the liver and spleen during intravenous AAV injections serves as a method to lower toxic effects on these organs. Before clinical approval vector administration techniques require thorough optimization of complex surgical procedures. It is important to know that multiple of these techniques have received approval for clinical use with different drugs and treatments.

AAV Transport within the CNS

- Intracellular movement of AAV within the CNS

Following vector administration and binding to cell surface attachment factors like glycans AAV vectors demonstrate both interstitial and intracellular movement within the CNS. Recent research on primate brains indicates that AAVrh.10 vector transduction patterns differ based on the administration route used. The parenchyma delivery route tested among five options emerged as the most effective method for gene transfer compared to the intraventricular and intraarticular administration routes. Research on marmosets proved that intravenous AAVrh.10 administration achieves effective transduction of the central nervous system. The findings indicate multiple factors including brain physiology and variables such as vector serotype and receptor usage across different animal models contribute to the diversity of AAV vector transport mechanisms. Two mechanisms called paravascular CSF transport and axonal transport seem to influence how AAV vectors spread through the CNS despite not being fully understood. Research confirms that the movement of CSF through paravascular pathways significantly controls the distribution of interstitial fluid (ISF) throughout the CNS.

- Intracerebral distribution of AAV

Early research found that protein build-up occurs in highly vascularized areas of the forebrain and brainstem shortly after ICV injections. Direct evidence indicates that changes in blood pressure induced through medical procedures regulate the distribution of nanoparticles such as AAVs throughout the brain. The brain differs from other organs because it does not have lymphatic circulation. Researchers investigated compensatory mechanisms in the CNS during 2012 by performing injections of molecular tracers ranging in size from 750 daltons to 2000 kilodaltons. The authors determined that paravascular CSF movement serves as a clearance pathway for solutes in the CNS based on clear 2-photon microscopy images. The para-arterial entrance and paravenous exit of subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid remove metabolic waste and additional solutes from brain tissue. The research findings imply that CSF transport mechanisms might influence how viruses spread throughout the central nervous system.

Safety Aspects of Adeno-associated Viral Vectors

- Immune response

Host chromosomes fail to incorporate recombinant AAV vector genomes effectively as these genomes mainly exist in episomal states. By avoiding chromosomal integration, recombinant AAV vectors prevent the insertional mutagenesis that is commonly seen with retroviral vectors. Host cellular machinery performs second strand synthesis as well as transcription and translation for the vector genomes. The safety evaluation of AAV vector genome persistence within the CNS remains to be published and general reviews of this topic exist in current literature. The overexpression of non-self transgenes through rAAV vectors can cause immune responses because the transgene product gets presented as an antigen to the immune system. Injecting primates directly into the brain with AAV1 containing a humanized Renilla GFP transgene generated an immune response toward the expressed reporter protein. Rats injected with AAV9 vectors carrying either the GFP reporter transgene or the human L-amino acid decarboxylase transgene demonstrated both cell mediated immune responses and neuronal loss.

- Intrinsic toxicity

Recent studies demonstrate that selected AAV serotypes experience systemic leakage which produces unintended biodistribution to organs including liver and spleen. Early research with animal models shows the necessity of developing a deeper comprehension of factors that affect toxicity and biodistribution profiles and immune responses in AAV-mediated CNS gene transfer. The safety of AAV vectors depends on the manufacturing methods as well as downstream processing and purity controls. Detailed evaluations of viral gene transfer vectors concerning packaging capacity, chromosomal integration in hosts and biosafety aspects are available in another source.

References

- Daci, R.; Flotte, T.R. Delivery of adeno-associated virus vectors to the central nervous system for correction of single gene disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(2), 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25021050.

- Murlidharan, G.; Samulski, R.J.; Asokan, A. Biology of adeno-associated viral vectors in the central nervous system. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2014, 7: 76. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2014.00076.

- Minetti A. Unlocking the potential of adeno-associated virus in neuroscience: a brief review. Mol Biol Rep. 2024, 51(1): 563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-024-09521-6.

- Słyk, Ż.; Stachowiak, N.; Małecki, M. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus vectors for Gene Therapy of the Central Nervous System: delivery routes and clinical aspects. Biomedicines. 2024, 12(7), 1523. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12071523.

- Kaiser, V.M.; Gonzalez-Cordero, A. Organoids-the future of pre-clinical development of AAV gene therapy for CNS disorders. Gene Ther. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-025-00527-8.

- Aliev, T.I.; Yudkin, D.V. AAV-based vectors for human diseases modeling in laboratory animals. Frontiers in Medicine. 2025, 11:1499605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1499605.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.