siRNA in Infectious Diseases-Targeting Viral and Bacterial Threats

Introduction of siRNA in Infectious Diseases

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology is one of the most powerful tools used in the treatment of infectious diseases. The discovery of RNA interference (RNAi) in the late 1990s opened new avenues for gene silencing and siRNA has been found to be effective in downregulating the expression of disease-related genes. The use of siRNA in the inhibition of viral RNA and inactivating viral replication, based on the natural RNAi pathway, is a significant step forward in the fight against infectious diseases. The process of using siRNA as a therapeutic option is customizable and can be made to target a specific viral genome rapidly. The versatility of siRNA has proven to be highly beneficial for emerging diseases, as there is often a need for rapid interventions. For example, siRNA has been used as a potential therapeutic option for the COVID-19 pandemic and it was shown that nucleic acid-based therapies can degrade the viral genome and adjust to mutations.

The urgency of treating Infectious Diseases

Premodern colonization, slavery and war contributed to the spread of infectious diseases across the world. Infectious diseases were able to travel along with their human hosts wherever they went and major human diseases like tuberculosis, polio, smallpox and diphtheria were widespread; before the availability of vaccines, they were a source of great morbidity and mortality. Rinderpest spread through trading paths and military movements causing serious effects on livestock and dependent human populations. The overall toll of mortality and morbidity from infectious diseases in recent decades has been reduced through medical advances, access to health care and sanitation, particularly for lower respiratory tract infections and diarrhoeal disease. The swift development of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine revealed modern science's rapid response capacity to new pathogens.

Delivery Challenges of siRNA-based therapeutics

- Extracellular challenges

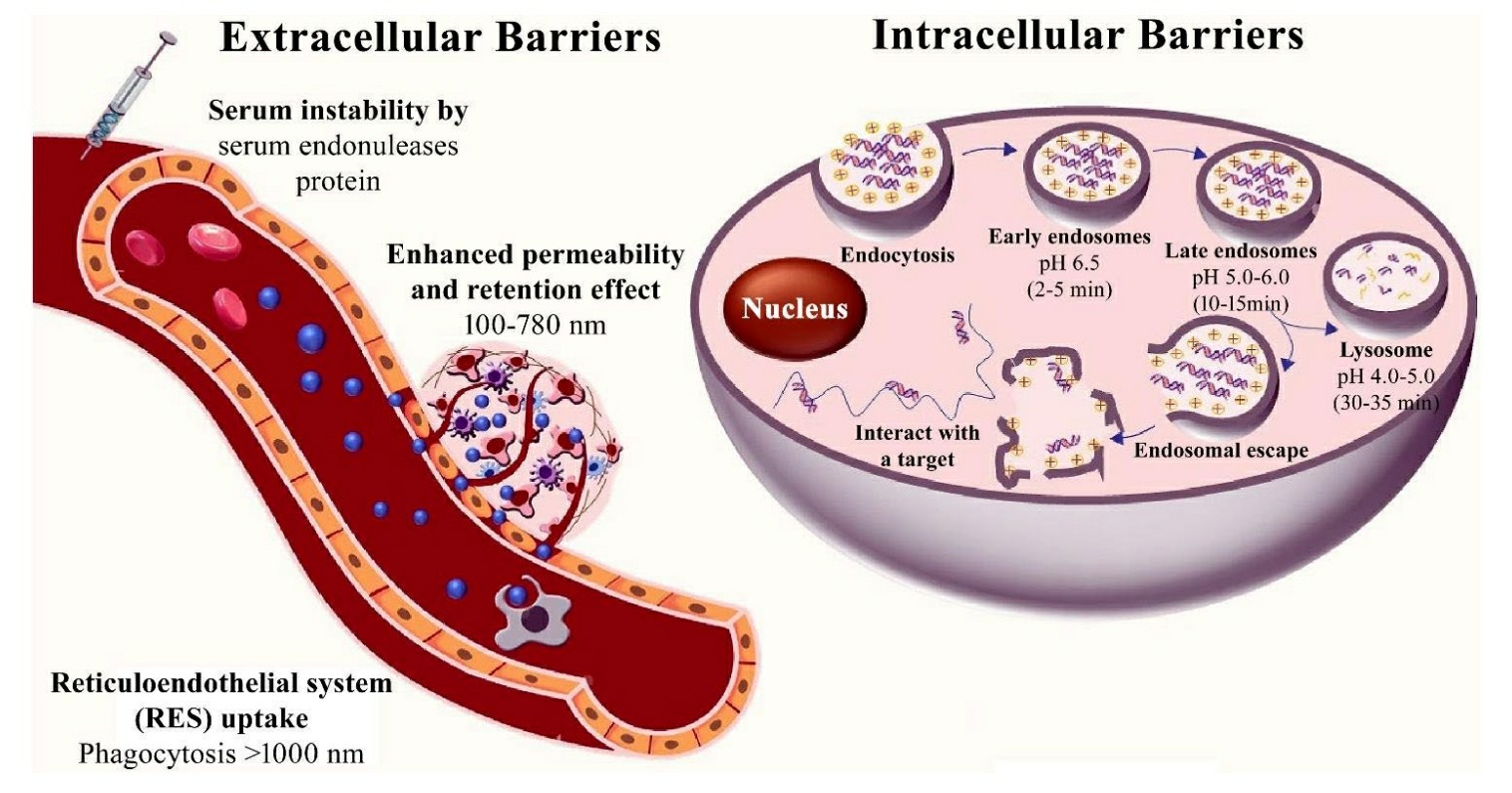

The small size of synthetic siRNAs (19-23 nt) and their low molecular weight facilitate rapid renal clearance and have a very short half-life in circulation (6 min-1 h). Moreover, the anionic nature of synthetic siRNAs is likely to induce RES-mediated opsonization and clearance from circulation. Another mechanism for siRNA clearance is receptor mediated uptake of siRNAs by RES cells expressing scavenger receptors and mannose receptors. In order to increase the pharmacokinetic properties of siRNAs and reduce clearance by the RES, modifications to the structure of siRNAs have been made. One approach has been to add polymers such as PEG to decrease recognition of siRNAs by serum proteins and RES receptors. Another strategy has been to utilize delivery systems such as lipid-based nanoparticles to shield siRNAs from RES receptors and increase circulation time. Chemical conjugates such as cholesterol have also been successfully used to improve siRNA stability and decrease clearance. These modifications have successfully improved siRNA pharmacokinetics and decreased clearance by the RES in numerous studies.

- Intracellular challenges

Upon internalization, siRNA-containing complexes are entrapped in endosomes, small vesicles that are membrane bound and responsible for sorting and transporting the material in cells. In this context, endosomes undergo a maturation process consisting of several stages (early and late endosomes and lysosomes). During maturation, the pH in the endosome lumen decreases and consequently siRNA is released from the complex into the cytoplasm. However, siRNA delivery can be hindered by endosomal nuclease activity and entrapment in non-productive endosomes. Large siRNAs are more susceptible to entrapment and the use of cationic materials for delivery may result in entrapment by endosomal membranes. Serum also allows for entrapment of siRNA as a protein-siRNA complex in the extracellular environment. There are two ways for siRNA to escape endosomes, which are membrane fusion and membrane disruption. In the first mechanism, siRNA-containing endosomes fuse with the plasma membrane and release the siRNA into the cytoplasm. In the second mechanism, siRNA-containing endosomes are disrupted by the creation of pores in the endosomal membrane. These pores are created by cationic peptides or polymers that cause lysis of the endosomal membrane and the release of siRNA into the cytoplasm.

Fig. 1 Extracellular and intracellular barriers for siRNA therapeutics1,6.

Fig. 1 Extracellular and intracellular barriers for siRNA therapeutics1,6.

Strategies for design of siRNA therapeutics for Infectious Diseases

Chemical modifications alter siRNA molecular structure but formulation-based modifications involve encapsulating siRNA within a delivery vehicle or modifying its formulation. Nucleotide modifications can be made to the base, sugar, or nucleoside depending on the nucleotide of interest. Uridine can be substituted for 2'-O-methyl uridine (2'-OMe U), a common base modification in siRNA, which has been reported to improve siRNA stability and reduce off-target effects. Phosphonate modifications involve substituting the phosphodiester backbone with a methyl group linked phosphonate bond and replacing one non-bridge oxygen atom in the phosphodiester bond with a stable non-ionic methylphosphonate (MeP) backbone modification. Another phosphonate backbone modification is substituting both of the non-bridging O2 of the phosphodiester bond with sulfur atoms to form a chemically stable, nuclease-resistant linkage called a phosphorodithioate (PS2) backbone modification. The stability and efficacy of siRNA in preclinical cancer and viral infection models surpass that of unmodified siRNA when PS2-modification is applied.

siRNA Applications in Viral Infections

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

No antiviral RNAi drug has been approved for clinical use. The first RNAi-based drug to enter human clinical trials is ALN-RSV01, a single siRNA targeting the mRNA of the nucleocapsid protein of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). It was evaluated as a potential treatment or prophylaxis for RSV. ALN-RSV01 was studied in a phase IIb clinical trial with RSV infected lung transplant patients. Naked siRNA was administered via the respiratory route. The clinical trial failed to reach the endpoints and only marginally reduced the incidence or progression of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, which was not statistically significant. The need for better siRNA stability was identified as an area for further development of siRNA-based therapeutics. This could include chemical modification of siRNA and the use of nanocarriers for improving delivery.

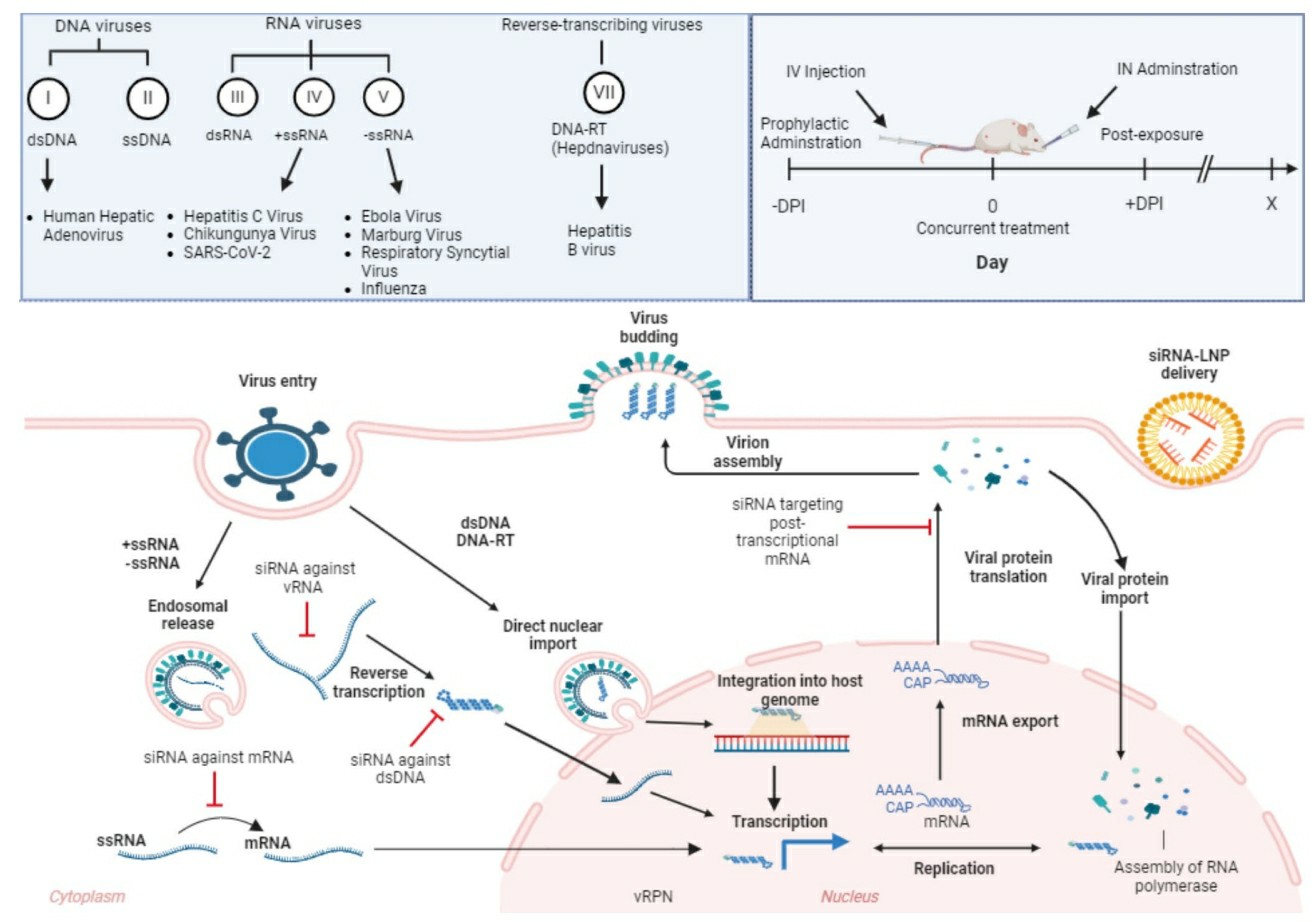

Fig. 2 Strategic Intervention of siRNA Therapeutics Across Viral Life Cycles and Delivery Timelines2,6.

Fig. 2 Strategic Intervention of siRNA Therapeutics Across Viral Life Cycles and Delivery Timelines2,6.

- Hepatitis B virus

The antiviral activity of VIR-2218, a GalNAc-conjugated siRNA, was demonstrated in a phase II trial involving participants with chronic hepatitis B infection. JNJ-3989, a siRNA conjugated Gal/NAc which blocks all hepatitis B virus transcripts, demonstrated efficacy in a phase II trial. It reduced the levels of hepatitis B surface antigen in both hepatitis B e antigen-positive and B/e antigen-negative patients and was well tolerated.

- HIV

In May 2007, the FDA gave approval to clinical trial phase I of an RNAi therapy, using a lentiviral vector infecting nondividing cells for HIV-1. Nonetheless, the siRNAs against HIV are still in the clinical phase I stage due to the lack of a comprehensive animal model to test in vivo therapeutic agents such as RNAi.

- Flaviviridae

The family consists of spherical enveloped viruses with linear, single-stranded positive sense RNA genomes. It includes human pathogenic viruses like HCV, Dengue virus (DENV) and West Nile virus (WNV). Hepatitis C virus infection may lead to permanent liver damage, hepatocellular carcinoma and death. The different segments of the 5' UTR of the virus genome were targeted by siRNA in Huh-7 cells and the resultant activity was reduced up to 85%. SiRNAs were designed against WNV 3' UTR and expressed from a plasmid-based system in Vero cells, which led to suppression of WNV replication in a sequence-specific manner, and thus indicated the role of 3' UTR in WNV pathogenesis. Dengue virus causes a severe disease which threatens the public health worldwide in the tropical and subtropical areas. Exogenously administered siRNA targeting the conserved 5' cyclization sequence segment of the DENV genome showed reduced the viral titers of various DENV strains in mice, suggesting the use of siRNAs to combat diverse dengue strains. Zika virus emerged as a global health threat and significant research efforts are underway to combat the pathogen. SiRNA-mediated silencing of the host endoplasmic reticulum membrane complex protein components was also reported to block the replication of various Zika virus strains in HeLa cells..

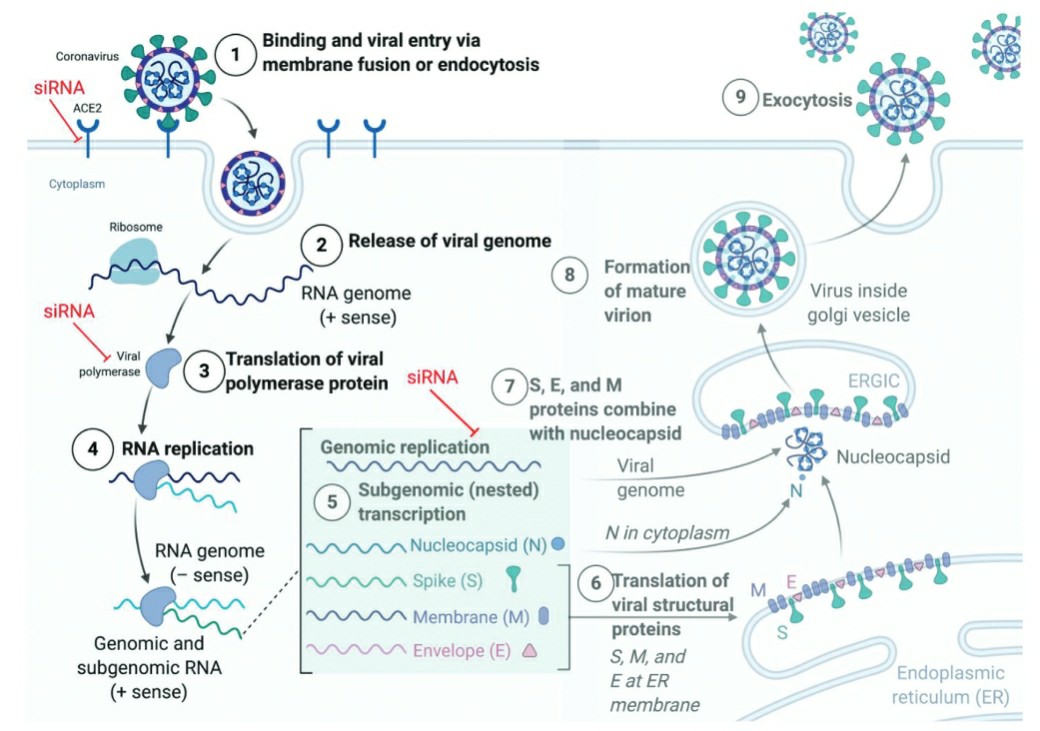

- SARS-CoV

As a novel virus emerges, RNA based technologies such as RNAi or mRNA offer a reliable and targeted approach to combat the SARS-CoV-2, once the genome is sequenced. RNAi allows addressing the origin of the infection instead of palliating the disease's symptoms both in prophylactic or curative ways. Labs around the world scrambled to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genome and identified conserved regions essential for the viral survival and replication for targeting with siRNAs and vaccines. Alternatively, host factors involved in trafficking of the virus can in principle be silenced by siRNA. Compared to modulating host factors such as ACE2, TMPRSS2, or the endocytic pathways involved in the internalization of the virus, silencing viral proteins with siRNAs is safer, more direct and more effective. siRNAs targeting the 3'UTRs of the pathogen inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV in Vero-E6 cells. siRNAs against SARS-CoV relieved viral fever, reduced viral levels, and lower acute diffuse alveoli damage in macaques.

Fig. 3 The SARS-CoV-2 infection lifecycle.3,6

Fig. 3 The SARS-CoV-2 infection lifecycle.3,6

siRNA Applications in Bacterial Infections

Immunotherapy with siRNA has been used for tuberculosis treatment. Once the immune system is stimulated by Mtb, it builds a "wall" around the bacterium with granuloma consisting of macrophages, lymphocytes and highly differentiated cells like multinucleated giant cells, epithelioid cells and foamy cells to constrain the infection but can also promote the dormant state of the bacteria that can then activate and proliferate later. A way to inhibit bacterial growth is to use siRNAs to inhibit the immunosuppressive cytokines. The chemokine XCL1 produced by CD8 T cells is activated during Tuberculosis (TB) infection, and its function is to play a major role in the formation of granuloma. A study has reported that aerosolized siRNA-targeting XCL1 was delivered to the lung using an intratracheal microsprayer to Mtb-infected mice, which induced local and transient reduction of XCL-1 by 50%. In addition, anti-TGFβ siRNA treatment of IL-10 knockout mice can downregulate both TGF-β and IL-10 levels, and this also leads to decreased bacterial burden. Another way to reduce type I IFNs is to downregulate them using siRNAs.

Future Directions

One of the biggest challenges of siRNA therapy is getting the siRNA to the target cell or tissue and across the biological barriers such as the cell membrane. Nanoparticles and viral vectors are being researched to help overcome this issue. Nanoparticles, such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and polymeric nanoparticles, have shown potential to protect the siRNA from degradation, increase cell uptake and allow delivery across the biological barriers. LNPs have been used to deliver siRNA targeting tat and rev genes in HIV and shown promising reduction in viral replication. However, LNP has toxicity issues and needs to be administered intravenously, which can be addressed by further formulation work. Viral vectors such as AAV vectors have been researched to target specific tissues with siRNA. AAV vectors are able to deliver stable and long-lasting transgene expression in non-dividing cells and have shown potential for siRNA delivery to the brain. Bioconjugates have also been explored where the siRNA molecules are covalently conjugated to specific molecules to aid in delivery and uptake. GalNAc-conjugated siRNA has been used to target the liver with high efficiency and specificity.

References

- Ali Zaidi, Syed Saqib, et al. "Engineering siRNA therapeutics: challenges and strategies." Journal of Nanobiotechnology 21.1 (2023): 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02147-z.

- Idres, Yusuf M., Adi Idris, and Wenqing Gao. "Preclinical testing of antiviral siRNA therapeutics delivered in lipid nanoparticles in animal models–a comprehensive review." Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2025): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-025-01815-x.

- Mehta, Aditi, Thomas Michler, and Olivia M. Merkel. "siRNA therapeutics against respiratory viral infections—What have we learned for potential COVID‐19 therapies?." Advanced healthcare materials 10.7 (2021): 2001650. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202001650.

- Kang, Hara, et al. "Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutic applications against viruses: principles, potential, and challenges." Journal of Biomedical Science 30.1 (2023): 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-023-00981-9.

- Ebenezer, Oluwakemi, et al. "Recent update on siRNA therapeutics." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26.8 (2025): 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26083456.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.