siRNA in Neurodegenerative Diseases-Targeting the Unreachable

Introduction of siRNA in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are a clinically diverse set of neurological disorders that negatively impact the lives of millions of individuals worldwide, and are characterized by the progressive loss of neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system (PNS). The failure of the architecture and functionality of neuronal networks and the loss of neurons, which lack an effective means of self-renewal given their terminally differentiated state, lead to the erosion of the fundamental communicative wiring and, eventually, to memory, cognitive, behavioral, sensory and/or motoric dysfunction.

The effect of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated gene silencing is achieved through a very precise and efficient mechanism called RNA interference (RNAi). Upon introduction of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into the cell, it is cleaved by the enzyme Dicer into small siRNA molecules. The siRNA molecules are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a multi-protein complex that is responsible for gene silencing. Upon incorporation into RISC, the siRNA duplex unwinds and only the guide strand remains bound to RISC while the passenger strand is released. The guide strand within RISC targets and binds to complementary sequences on the target mRNA. The endonuclease activity of the Argonaute protein in RISC cleaves the target mRNA, resulting in its degradation and thus preventing the production of the target protein.

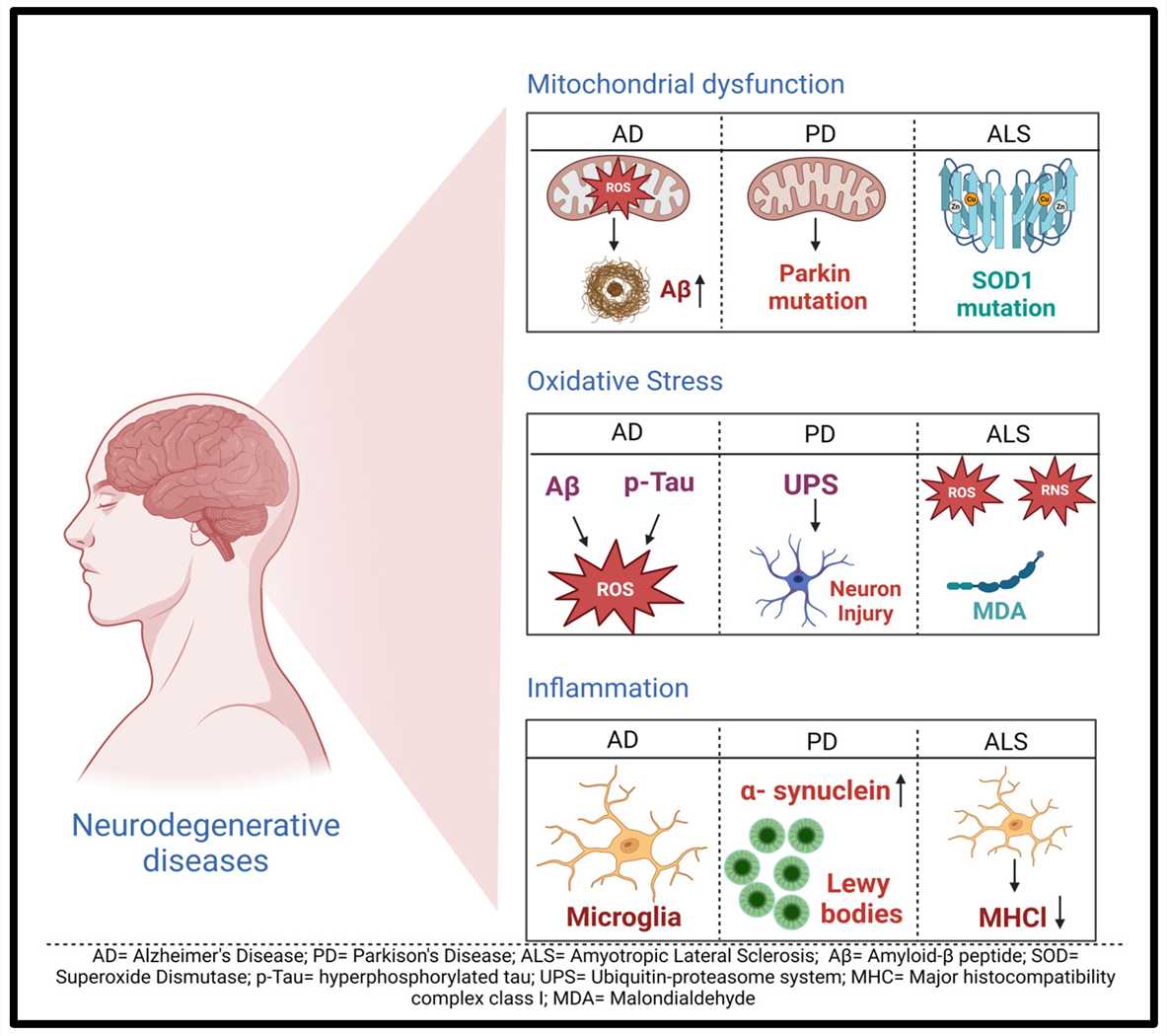

Fig.1 General mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases1,5.

Fig.1 General mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases1,5.

siRNA Delivery Challenges in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Long (naked) siRNAs have relatively short half-lives (minutes to hours) in the extracellular environment because they are susceptible to enzymatic degradation by enzymes in the serum and in tissues. Achieving target-site accumulation to a level of silencing that is therapeutically meaningful is difficult. To be effective in the disease environment, siRNAs must not only survive in the serum, but also accumulate in the target cells in the tissue where the aberrant gene (or genes) of interest is (are) expressed. Having accumulated in their target cells, siRNAs face several challenges before they can exert their gene silencing function. Their large size and negative charge prevent their diffusion across the plasma membrane and accumulation in the cytoplasm. siRNA delivery strategies that exploit endocytosis also must facilitate endosomal escape. And even after cytoplasmic entry, siRNAs are susceptible to intracellular RNAses and must be recruited by and assembled into RISC with high efficiency.

Key points of siRNA design in Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Length of siRNA

SiRNAs are now routinely designed at between 19 and 29 nucleotides in length. Shorter siRNAs have a greater tendency for off-target effects, but siRNAs from 19–25 nucleotides in length have similar silencing potency. Shorter siRNAs are used for this reason, as long siRNA can induce an antiviral inflammatory immune response. This side effect can currently be avoided with chemical modifications to the nucleotides. Host endosomal and intracellular innate immune pattern recognition receptors may confuse synthetic RNA for viral RNA. Toll-like receptors (TLR-3, TLR-8, and TLR-9), retinoic acid inducible gene I receptor, and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase). Interferon-α and interferon-β (Type I interferons) and inflammatory cytokines are produced in response to this. The activated protein kinase causes inhibition of mRNA translation and cell death through phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha. A way to avoid activating the immune system is to design siRNAs with specific sequence patterns or high "U" content (both of which are recognized by TLRs). However, shorter siRNA (< 24 bp) or chemically modified siRNA (preventing activated protein kinase) and 3'-overhangs that evade retinoic acid inducible gene I receptor immune sensing can be used.

- GC content of siRNA

One of the basic requirements for siRNA is GC content, which is estimated by algorithms and is usually somewhere between 30 and 60%. Low GC content results in a weaker binding affinity or nonspecific binding, while high GC content can prevent the unwinding step performed by helicase and may hamper the incorporation into the RISC complex. However, low GC content between nucleotides 9 and 14 improves the RISC function during mRNA cleavage. Some regions in the sequence may form stable secondary structures in the sense or antisense strand and should be avoided (for example, internal repeats, palindromes, CCC or GGG). The formation of a stable duplex is required for functional siRNA. In addition, sequences that contain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), miRNA seed matches, or known toxic motifs should be avoided. Unbalanced nucleotide content in the duplex and weak base pairing at the 5'-end of the antisense strand are very important to prevent the antisense strand being preferentially loaded into the RISC complex ('strand bias'). This means that more A/U at the 5'-end of the antisense strand and more G/C at the 5'-end of the sense strand reduce the chance of sense strand incorporation into RISC and the associated off-target effects.

- siRNA Modifications

Different modifications have been introduced in order to improve the function of siRNA and other siRNA characteristics. Because nucleotides are the basic building blocks of RNA, nucleotides usually contain a ribose sugar with a 1'-nucleobase group and a 3'-phosphate group. RNA nucleotides can be categorized as phosphonate modifications, base modifications and ribose modifications. The most common type of nucleotide modification of siRNA is 2'-O-methyl which increases siRNA stability and half-life, increases the affinity of siRNA to target mRNA and reduces the immunogenicity. Other analogs were introduced as well such as 2'-O-methoxyethyl (another very useful and popular analog), that promotes higher binding affinity to RNA and is more resistant to nuclease attack. Another common analog is the replacement of the 2'-OH group with the highly electronegative fluorine such as 2'-deoxy-2'-fluoro (2'-F) or 2'-arabino-fluoro. The 2'-F modification is one of the most commonly used modifications in clinical and pre-clinical siRNAs and creates a C3-endo conformation, which is favorable for binding. 2'-O-benzyl and 2'-O-methyl-4-pyridine can increase activity when placed at positions 8 and 15 of the siRNA guide strand.

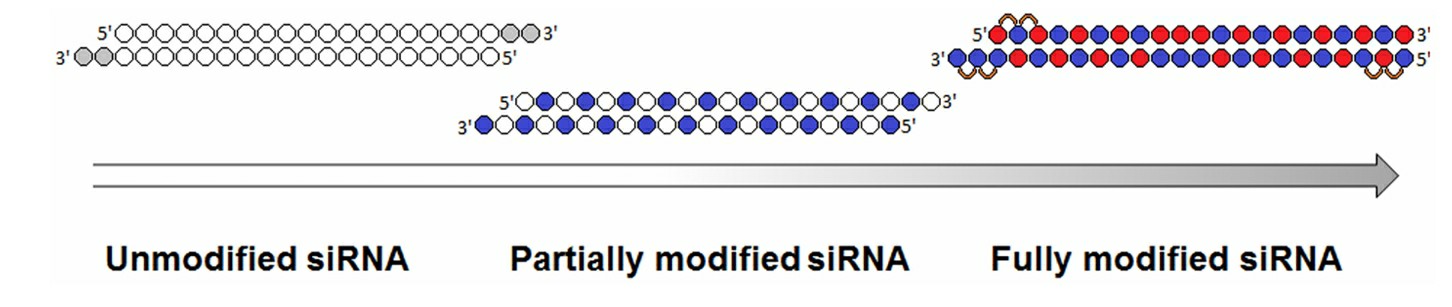

Fig. 2 Evolution of siRNA chemical modification patterns2,5.

Fig. 2 Evolution of siRNA chemical modification patterns2,5.

siRNA Applications in Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Alzheimer's Disease

RNAi has been considered as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). One of the main targets is the β-secretase (BACE1), which is responsible for the production of Aβ. One study was conducted by using a lentiviral vector to deliver siRNA against BACE1 in a transgenic mouse model of AD. The results showed that BACE1 silencing reduced the formation of amyloid plaques and improved the neuropathological and behavioral symptoms. Another study used a galactosylated triple-interaction stabilized polymeric siRNA nanomedicine (Gal-NP@siRNA) to overcome the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and silence BACE1. The cognitive capacity was improved in AD mouse models. The results indicated that siRNA therapy can reduce the progression of AD through the silencing of genes involved in the formation of amyloid plaques and improving cognitive function.

- Huntington's Disease

In Huntington's disease, therapeutic application of siRNA has been tested as a way to suppress the expression of the mutant huntingtin gene (mHTT), which causes HD. One innovation is the use of divalent siRNA (di-siRNA), which has been shown to have improved mHTT suppression. Delivery of di-siRNA into the CSF of animal models led to sustained silencing of the mHTT gene and resulted in reduced levels of mHTT and improved disease symptoms. The delivery of siRNA through the CSF could be an attractive way to achieve long-lasting gene silencing in the central nervous system.

- Cerebral Ischemic Stroke

One recent study afforded the opportunity to examine the acute and sustained effects of siRNA injection with repeated administration of siRNA targeting one neuroinflammatory pathway. G-protein coupled receptor 17 (GPR17) has been proposed to play a role in post-ischemic neuroinflammation. GPR17 expression was knocked down by antisense oligonucleotides and proved beneficial in stroke, however, this was achieved by knocking down GPR17 siRNA in microglia at both 14 days and 24 hours after injury. This is important because knockdown at the 14-day mark (but not at 24 hours) reduced microglial activation. Post-injury microglial activation has been shown to be dual; while the activation immediately following the injury has been shown to be beneficial, prolonged post-injury activation is considered detrimental. A well-known factor released from necrotic cells during the post-ischemic neuroinflammatory phase is high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Knockdown of HMGB1 with siRNA injected intracortically after ischemic injury was protective by reducing microglial activation and decreasing neuronal apoptosis. Subsequent experiments with intranasal administration of siRNA against HMGB1 in a rat model of tMCAo showed a significant knockdown of HMGB1 in the brain, but not the liver, lung, kidney, or heart.

- Non-Traumatic Brain Hemorrhage

In a rat model of SAH, siRNA against CHOP was injected 24 h prior to injury to prevent the CHOP-mediated death of endothelial cells. Pre-treatment of the rat with siRNA against CHOP decreased mortality, improved neurological recovery, decreased BBB disruption, and decreased edema. Decreased Bim (Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death), increased beclin-2, and decreased cleaved caspase-3 were associated with decreased cell death and better neuronal cell survival. Other studies in this model found that pretreatment with siRNA against CHOP decreased the changes in cerebrovascular blood vessel phenotypes such as a decreased diameter and wall thickness in the basilar artery in the treated rats following SAH, similar to previous observations. The narrowing of the artery and thickening of the wall can contribute to further damage, but decreases in this phenotype from siRNA against CHOP may indicate that pretreatment is a positive treatment. In another rodent model of SAH, siRNA against p53 up-regulated modulated regulator of apoptosis (PUMA) was also shown to decrease mortality, improve neurological scores, decrease BBB disruption, and decrease cerebral edema.

Strategies for siRNA delivery to the brain

- Crossing the BBB

The main mechanism by which the siRNA-based delivery systems enter the brain following i.v. administration is the receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT). Cerebral endothelial cells express various receptors including insulin, transferrin, lactoferrin and low-density lipoprotein receptors. Modifications on the receptor associated ligands of NPs surface can enhance the BBB permeability of the siRNA-based delivery systems through the RMT pathway. Opening the tight junctions of the BBB is another strategy to enhance the permeability of the BBB and to facilitate the delivery of NP into the brain through the paracellular pathway. Strategies that can open the BBB are intra-arterial infusion of hyperosmotic mannitol, radiotherapy and low-frequency focused ultrasound combined with intravenous administration of microbubbles. By these approaches, the efficiency of the delivery of nanoparticles into the brain was significantly enhanced.

- Intranasal administration

Intranasal administration avoids the BBB and targets the brain without going through the digestive system and liver, thus bypassing first-pass metabolism and inactivation of most drugs. However, intranasal administration is not free of disadvantages: Nasal cilia are in motion and may impair the drug-mucosa contact time, and may lose the drug in the nasal cavity. Additionally, the small volume of the nasal cavity limits the dosage.

- Intracerebral administration

The fastest and most effective invasive method of delivering siRNA into the brain is direct injection into the brain. Intracerebral administration can achieve higher drug concentrations in the brain lesions and minimize drug concentrations in other parts of the brain and the systemic circulation. The intracerebral injection can be divided into four categories according to the injection site: intracerebroventricular injection, hippocampal injection, nuclear injection, intrathecal injection, and ventral tegmental area injection. Different types of injections are chosen according to the location of the lesion and the type of disease. Advanced techniques and equipment are needed for the injection. Injection may also cause infection and neurotoxicity.

References

- Anilkumar, Adithya K., et al. "Long non-coding RNAs: New insights in neurodegenerative diseases." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25.4 (2024): 2268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042268.

- Chernikov, Ivan V., Valentin V. Vlassov, and Elena L. Chernolovskaya. "Current development of siRNA bioconjugates: from research to the clinic." Frontiers in Pharmacology 10 (2019): 444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00444.

- Sajid, Muhammad Imran, et al. "Overcoming barriers for siRNA therapeutics: from bench to bedside." Pharmaceuticals 13.10 (2020): 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13100294.

- Ali Zaidi, Syed Saqib, et al. "Engineering siRNA therapeutics: challenges and strategies." Journal of Nanobiotechnology 21.1 (2023): 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02147-z.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.