The Miracle of Gene Therapy: From Principle to Application

What is Gene Therapy?

Gene therapy involves treatments that introduce foreign genetic material into cells or organs to cure diseases or provide major clinical benefits. Developing sophisticated delivery platforms is essential to achieve therapeutic efficacy in these interventions because they enable efficient gene transfer to diverse biological systems and minimize adverse effects while maintaining safety. Under regulatory classifications gene therapy products fall into the category of advanced biological therapeutics because of their unique molecular and functional properties.

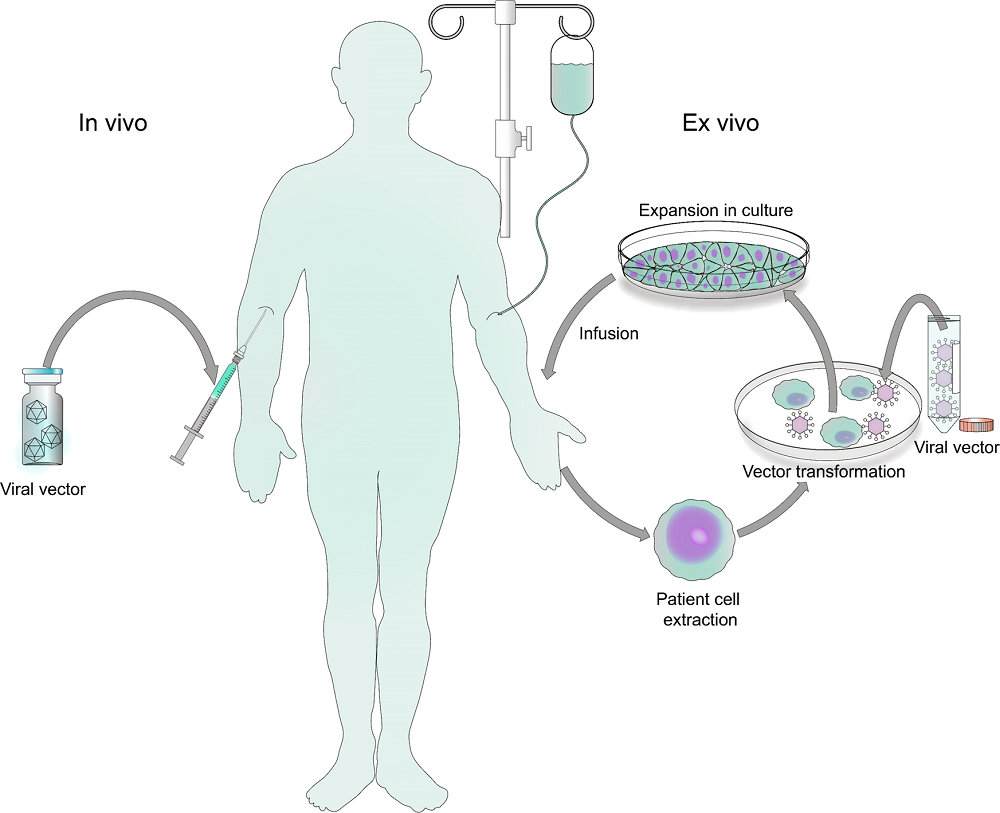

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) specifies that such products must meet two essential criteria: Gene therapy products must include a recombinant nucleic acid component that works to alter genetic sequences by regulating repair or inserting/deleting sequences in human bodies. The EMA makes a clear distinction by excluding infectious disease vaccines from this category. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines gene therapy as therapeutic interventions which produce biological effects either through the transcriptional/translational activity of delivered genetic material or by genomic integration. Gene therapy products exist in forms like naked nucleic acids or viral vectors and genetically modified microorganisms which can be delivered through direct in vivo cellular modification or ex vivo cell manipulation preceding transplantation.

Fig.1 Summary of viral gene therapy modalities.1

Fig.1 Summary of viral gene therapy modalities.1

History and Development of Gene Therapy

Discovery of reverse transcriptase and viral gene transfer

Ten years after scientists discovered gene transfer between bacteria using bacteriophages, Researchers identified a similar process in viruses which demonstrated that genetic changes can be passed through viral infections. Through the experimental work with Rous sarcoma virus-infected avian cells, researchers showed that viral genetic modifications encoding replication information remained stable within the host cells. The central dogma of molecular biology faced a challenge from this critical discovery which demonstrated reverse genetic information transfer within RNA viruses. Through the research, researchers proved the possibility of RNA-to-DNA information transfer and led scientists to discover reverse transcriptase enzymes (RNA-dependent DNA polymerases). This research clarified how stable genetic inheritance works by showing that exogenous nucleic acid sequences can integrate into host chromosomes leading to permanent phenotypic changes.

Researchers led the medical field into a new era in 1990 when he conducted the initial human gene therapy trial making use of recombinant DNA technology. The groundbreaking medical endeavor had roots in researchers' successful demonstration of genetic modification feasibility with murine models through experimental work. Researchers successfully integrated exogenous dihydrofolate reductase and herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase genes into mouse hematopoietic stem cells which led to successful engraftment and partial bone marrow regeneration in recipient animals. After confirming his preclinical results, researchers aimed to adapt his findings for application in human β-thalassemia patients. Beta-globin gene mutations impair hemoglobin synthesis in this genetic disorder which leads to severe transfusion-dependent anemia. Researchers initiated clinical treatments on two β-thalassemia patients located in Italy and Israel before receiving formal approval from the UCLA Human Subjects Committee after submitting the research protocol.

Clinical milestones in human gene therapy trials

Researchers began the inaugural clinical trial with a therapeutic transgene following the initial work with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and before he explored tumor necrosis factor gene therapy. The FDA gave its authorization for this groundbreaking research on September 14, 1990 to address ADA-SCID which is a monogenic condition that leads to severe combined immunodeficiency. The clinical trial included two young patients who received their own leukocytes genetically engineered outside the body to produce active adenosine deaminase. The first patient experienced temporary clinical progress but the other participant showed significantly weaker therapeutic results. The concurrent administration of polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase (PEG-ADA) enzyme replacement therapy complicated outcome interpretation for the case. The European Union launched its own ADA-SCID trials after the initial study which served as a catalyst for broader gene therapy research targeting multiple genetic diseases. The initial Scandinavian research effort that commenced gene transfer experimentation in 1995 delivered convincing proof of successful in vivo gene delivery together with expression within human neural tissue.

Can Gene Therapy Target All Cells?

The fundamental classification of gene therapy strategies separates them into two modalities according to their cellular targets and heritability which include germ line gene therapy and somatic gene therapy. Somatic gene therapy delivers genetic material into particular differentiated cells which limits therapeutic benefits to the treated patient while preventing inheritance by future generations. Germline gene therapy works on reproductive cells to create inheritable genetic changes which can be transmitted to future generations. The separation between these therapies has substantial regulatory consequences because existing laws only allow medical treatments to be conducted on somatic cells while banning germline cell alterations.

What is the Purpose of a Vector in Gene Therapy?

Gene therapy implementation faces its core challenge in creating efficient gene delivery systems that resolve both transduction efficiency and sustained transgene expression. Successful gene therapy requires reliable delivery systems that use specialized gene transfer vehicles called vectors to target specific tissues and cells. These delivery platforms are broadly categorized into two classes: Gene delivery systems encompass biologically derived viral vectors alongside synthetic non-viral systems. Gene therapy viral vectors fall into two main categories which depend on their genomic structure: RNA-based vectors and DNA-based vectors. The fundamental RNA viral vector technology mostly utilizes components from murine leukemia virus (MLV) to create retroviral vectors. The inherent limitation of retroviral vectors to infect quiescent cells can potentially be overcome with engineered lentiviral vectors derived from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and similar complex retroviruses. The adenoviral system and the adeno-associated viral (AAV) system stand out as the leading choices for DNA viral vectors. In vivo gene delivery has advanced with new vector technologies but current systems do not reach optimal performance which requires careful usage in clinical applications. Research continues to focus on enhancing vector platforms for gene therapy through improved safety measures and transduction efficiency.

The Types of Vectors for Gene Therapy

Non-viral vectors

Researchers utilize various non-viral gene delivery techniques which range from direct DNA injections to employing polylysine or cationic lipid complexes that assist in crossing cell membranes. Despite their versatility, these approaches are predominantly limited by two fundamental challenges: inadequate transfection efficiency and transient transgene expression. Non-viral gene therapy applications face considerable conceptual and technical challenges in maintaining long-term therapeutic gene expression even though multiple chemical enhancers have been created to boost delivery efficiency.

Viral vectors

Current gene therapy methods mainly rely on using viruses to deliver therapeutic genes since these viral systems have been genetically altered to remove their ability to cause disease. Through viral vectors researchers have developed a powerful method that uses viruses' natural ability to transfer and integrate genes into cells.

- Retroviral vectors

Retroviruses form a distinct viral category able to convert their RNA genomes into DNA inside host cells through reverse transcription. The retroviral genome consists of three essential structural genes (gag, pol, and env) and is bordered by long terminal repeats (LTRs) which enable genomic integration and define the viral sequence boundaries. LTRs serve as regulatory elements which manage viral gene expression by their enhancer-promoter activity. The packaging signal (ψ) serves as a vital cis-acting element that allows viral RNA to be selectively encapsidated while preventing cellular transcripts from being packaged. The development of producer cell lines together with the identification of the packaging signal led to the creation of replication-deficient vectors that perform reverse transcription and integrate into the genome. The γ-retroviral vectors created in the 1980s and early 1990s successfully delivered genes into hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Researchers developed C-type retroviruses to achieve effective transduction of primary T lymphocytes at the same time. Initial clinical applications emerged from these ground-breaking vector systems that targeted genetic defects in immunodeficiencies and malignancies by modifying patient-derived T cells and HSCs ex vivo.

- Lentiviral vectors

Lentiviruses represent a unique subgroup of retroviruses with the ability to transduce both dividing and dormant cells. Scientists have genetically engineered human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the most extensively studied member of its family, to function as a powerful vehicle for delivering genes inside living organisms. Lentiviruses retain the standard gag, pol, and env genes of retroviruses while incorporating extra regulatory proteins (tat, rev, vpr, vpu, nef, and vif) that boost their biological complexity. Research findings show that lentiviral vectors establish long-term transgene expression for over six months across multiple rodent tissues such as neural and hepatic tissues and muscular, ocular and pancreatic islet cells while avoiding transcriptional silencing that conventional retroviral systems experience. The immunological effects of administering lentiviral vectors have not been fully described yet preliminary results demonstrate low cellular immune reactions at the injection sites and insignificant humoral responses after the delivery of 107 infectious units. The unique features of lentiviral vectors make them strong candidates for delivering long-lasting gene expression in live organisms.

- Adenoviral vectors

DNA-based adenoviruses can target both dividing and dormant cells to cause mild respiratory infections in people. The genomic structure of these viruses includes over twelve separate genes that stay independent genetic units inside the host cell nucleus instead of integrating into the host genome. Episomal viral DNA retains its capability to replicate independently inside the nucleus. The creation of replication-incompetent adenoviral vectors requires removing the E1 gene essential for replication and replacing it with a therapeutic transgene like factor IX's coding sequence together with an enhancer-promoter regulatory sequence. Engineered vectors need specialized cell lines to supply the E1 gene products in trans for effective propagation. The system generates recombinant viral particles at very high titers which usually fall between 1011 and 1012 viral particles for every milliliter.

Cells infected by recombinant adenovirus express therapeutic transgenes because the vectors are replication-deficient through the deletion of essential viral replication genes. Through efficient cell transduction in vivo these vectors achieve high-level transgene expression. The transgene expression produced by adenovirus-infected cells remains active only for a period of around 5 to 10 days following infection. Specific experimental models like nude mice or immunosuppressed animals treated with immunosuppressive drugs enable sustained transgene expression unlike retroviral vectors. The results indicate that the host immune system functions as a key limiting factor for the length of transgene expression driven by adenoviral vectors.

- Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors

The AAV represents a novel tool in gene therapy as a non-pathogenic virus that contains single-stranded DNA and has an uncomplicated genomic layout. The genome of the virus contains two crucial genes known as cap and rep which are positioned between inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) that mark the limits of the viral genome and hold the packaging signal. Structural proteins essential for capsid formation are produced by the cap gene and the rep gene product supports viral replication and site-specific integration. AAV requires helper viruses like adenovirus or herpes simplex virus to provide additional replication genes since it cannot reproduce independently.

The virus demonstrates a wide range of cellular tropism and achieves site-specific integration of its genome into human chromosomes when Rep protein is present. The creation of an AAV vector involves removing the rep and cap genes and substituting them with a therapeutic transgene. Scientists can produce up to 1011-1012 viral particles per milliliter yet infectious particles make up only 0.1–1% of this total. The production process presents technical challenges because the toxic effects of the Rep protein and specific adenoviral helper proteins have obstructed the creation of stable packaging cell lines that supply all essential components. To remove adenovirus contaminants purification steps must be thorough while the small size limit of 3.5-4.0 kilobases in packaging capacity prevents larger gene inclusion. The ability of viral proteins to trigger an immune response continues to pose a problem since about 80% of adults already have antibodies against AAV in their systems. Although multiple difficulties exist regarding AAV vectors they have shown promising results in preclinical studies. Human factor IX cDNA delivered to liver and muscle cells in immunocompetent mice produced therapeutic protein levels in circulation for over six months demonstrating AAV as a promising tool for in vivo gene therapy.

The Process of Gene Therapy

Gene therapy requires complex biological processes which scientists still do not fully understand at the molecular level. Gene therapy initiates with administering an appropriate vector that can be viral, non-viral or cell-based into the body through localized injections or systemic bloodstream delivery. Vectors need to find their way to the target tissue before penetrating the specific cells and crossing the cytoplasm to reach the nucleus. The therapeutic transgene undergoes transcription to mRNA inside the nucleus before mRNA translation forms the functional protein. This protein exerts its effects through various mechanisms: The protein can function within the cell itself or affect the cell that produced it through intracrine or autocrine signaling methods while nearby cells get influenced by paracrine actions and distant cells through systemic circulation using endocrine signaling pathways demonstrated by proteins such as erythropoietin and growth hormone. The protein needs to bind to its receptor to initiate a precise biological response that results in the targeted therapeutic effect.

Successful gene therapy shares fundamental requirements with other novel therapeutic interventions through its technical aspects of gene delivery and expression alongside clinical efficacy and safety together with socioeconomic considerations. Gene therapy presents unique technical difficulties which scientists must resolve. Successful gene therapy requires the identification of a suitable therapeutic gene that demonstrates well-established disease pathogenesis understanding together with precise targeting and sufficient biological potency while developing efficient gene delivery systems that provide targeted tissue specificity and high transfection efficiency with minimal toxicity. Robust systems for controlling gene expression play a crucial role in managing both the timing and level of therapeutic protein production. Gene therapy needs to show a positive risk-benefit balance while proving superior to existing conventional therapies which tend to be more affordable. Gene therapy will achieve mainstream acceptance and integration into medical practice once all essential criteria are fulfilled.

Translating Gene Therapy Principles into Practical Solutions

As outlined in this article, gene therapy requires sophisticated delivery systems and precise techniques to achieve therapeutic efficacy. Our company is specialized in providing comprehensive solutions for gene therapy development. With advanced facilities and expert scientists, we offer end-to-end services from early research to clinical applications, helping clients overcome technical challenges and accelerate their gene therapy programs while maintaining the highest quality standards.

Our Core Services and Products

| Category | Key Offerings |

|---|---|

| Viral Vector Development |

AAV Vector Development Adenoviral Vector Development Lentiviral Vector Development Herpes simplex virus vector |

| Nucleic Acid Services |

siRNA Screening Service Antisense Oligonucleotide (ASO) Development Circular RNAs (circRNAs) Services |

| Delivery Systems |

Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Formulation N-Acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) Conjugation Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates (AOCs) |

| Analytical Services |

Vector Identity and Titer Testing Safety and Potency Assessment Nucleic Acid Characterization |

| Therapeutic Nucleic Acids |

ASOs for Genetic Disorders siRNAs for Gene Silencing Circular RNAs for Gene Regulation |

| Recombinant Viral Vectors |

Recombinant AAV Recombinant Adenovirus Recombinant Lentivirus |

Contact our scientific team today to discuss how we can support your gene therapy program and help transform promising research into life-changing treatments.

References

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 53. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00487-6.

- Leikas, A.J.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Hartikainen, J.E.K. Adenoviral gene therapy vectors in clinical use—basic aspects with a special reference to replication-competent adenovirus formation and its impact on clinical safety. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2023, 24(22): 16519. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216519.

- Wang, S.; Xiao, L. Progress in AAV-Mediated In Vivo Gene Therapy and Its Applications in Central Nervous System Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2025, 26(5): 2213. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26052213.

- Goswami, R.; Subramanian, G.; Silayeva, L. Gene therapy leaves a vicious cycle. Frontiers in oncology, 2019, 9: 297. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00297.

- Ingusci, S.; Verlengia, G.; Soukupova, M. Gene therapy tools for brain diseases. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2019, 10: 724. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00724.