RNAi Mechanisms and Molecular Engineering

Introduction of RNAi Technologies

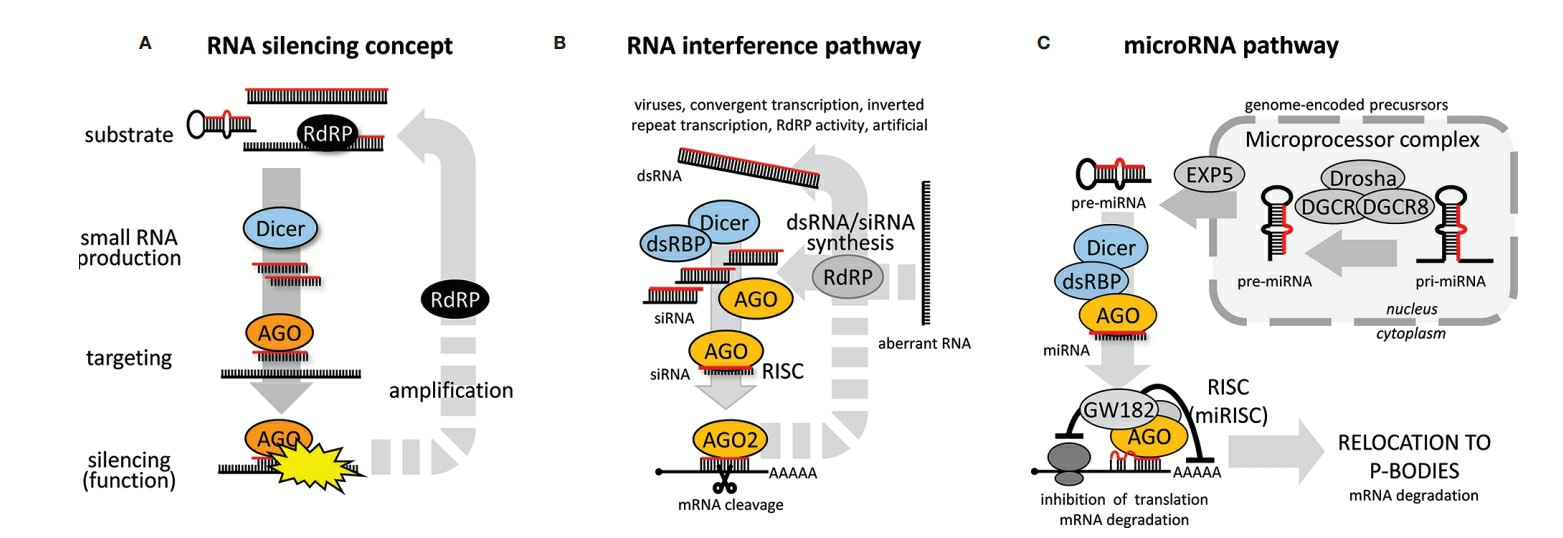

RNA interference (RNAi) is the pairing of a short RNA sequence to a 21-nucleotide endogenous mRNA target. It was first discovered in 1998, and many cellular processes are regulated by endogenous RNAi. Short, double-stranded RNAs are endogenously diced from longer RNA transcripts by Dicer, and then loaded into an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which contains several proteins, including Argonaute and transactivation response RNA-binding protein. The passenger strand is removed, and the guide strand is base-paired to a complementary mRNA sequence via the RISC complex. Therapeutically, RNAi is mediated by delivery of small RNA duplexes such as microRNA (miRNA), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) and Dicer substrate RNAs (dsiRNAs)(Table 1). The shRNA pathway is the most upstream, and requires nuclear processing; dsiRNA is next, and requires Dicer processing. The siRNA and miRNA pathways are the most direct, as they go from delivery to RISC loading. However, miRNAs are not 100% complementary to target sequences, while siRNAs are. This difference results in different silencing outcomes; miRNAs induce translational repression, while siRNAs induce Argonaute 2-mediated degradation.

Targeting Precision: Specificity and Off-Target Effects

- miRNA: The Multi-Target Maestro

A mature miRNA contains a seed sequence of 6–7 nucleotides between positions 2–7 at its 5' end which enables it to bind to multiple mRNAs in controlling gene networks. However, this is also a cause of off-target effects, which can affect the result of the experiment and the outcome of therapeutics. Due to the short seed sequence, miRNAs can bind to multiple sites of the 3'UTR of the mRNA. This pleiotropic effect is useful for controlling complex biological processes, but can also result in off-target effects. For example, off-target effects due to miRNA-like effects have been found to have a more substantial impact on phenotypes than on-target repression in siRNA screens, especially when large libraries are screened using a single-assay readout. Several methods have been proposed to mitigate off-target effects. These include using appropriate controls such as mismatches in positions 9-11 of the siRNA guide strand to assess off-target effects, performing rescue experiments using untargeted cDNA or orthologous genes to confirm phenotypes, and reducing siRNA concentrations and using multiple independent siRNAs or shRNAs.

Fig. 1 RNA silencing pathways1,5.

Fig. 1 RNA silencing pathways1,5.

- siRNA: Designed for Single-Gene Knockdown

Due to the double-stranded nature of siRNAs, this has led to their being more effective at performing a gene knockdown than miRNAs, as they can promote the specific degradation of the target mRNA. This very high level of specificity does have some disadvantages. One of the first observed off-target effects of siRNAs was published in 2003. Several siRNAs targeting the same gene were transfected into cells, and expression profiling with microarrays revealed that each siRNA gave a unique sequence-specific expression profile. Sequence analysis of the affected transcripts demonstrated that the off-target transcripts contained complementary regions in their 3' UTRs to the 5' end of the transfected siRNA guide strand. Strikingly, some of the off-target transcripts only contained 8 nt of complementarity to the siRNA. Later studies of siRNAs targeting a wide variety of transcripts demonstrated that each siRNA downregulated a set of transcripts enriched for transcripts containing complementary 3' UTRs to the 5' portion of the siRNA guide strand. Base mismatch in the 5' end of an siRNA guide strand decreased silencing of the original set of off-target transcripts, but introduced a new set of off-target transcripts containing 3' UTRs complementary to the mismatched guide strand.

- shRNA: Same as siRNA but with Long-Term Expression Risks

ShRNAs are hairpin RNAs (or small RNA) encoded by DNA and processed into siRNA-like small RNA by cellular enzymes. Like siRNAs, shRNAs have sequence homology to the target mRNA which will allow for the gene silencing mechanism. shRNAs are often used to enable long-term silencing, as they are stable, expressed from DNA vectors using RNA polymerase III promoters such as U6. This long-term expression can, however, be dangerous, such as if viral vectors are used to introduce them, they can cause insertional mutagenesis. They can also produce unintended siRNA, causing "off-target effects" by expression from a vector.

Optimal gene silencing strategy

- Design Modification

The degree of gene silencing varies based on siRNA, miRNA and shRNA sequence. Even minor changes in the sequence can dramatically affect the efficiency of gene silencing. For instance, changing the antisense strand sequence by mutations can cause non-recognition of homologous mRNA by the loaded RISC. The parameters affecting the efficacy of RNAi include thermodynamic stability, number of nucleotides in the siRNA sequence, the% of GC residues, secondary structure of the RNA, number of sites with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and number of repeats. Using commonly available computational design software one can synthesize potentially effective siRNA sequences. As mentioned above, designing miRNA, siRNA and shRNA are all identical since shRNA causes RNAi by creating a siRNA. So, siRNA designing software can be used to design shRNA sequence as well. However, there are some differences. In addition, for high level of shRNA expression, GC at position 11 and AU at position 9 is strongly preferred. In some cases, where siRNA software does not give good shRNAs, one has to generate many sequences and test to find the best shRNA. This can be time consuming and tedious because it requires cloning shRNA into plasmid. To solve this problem, one can buy several commercially available pre-designed shRNA plasmids and screen them.

- Backbone and Structural Modification

Despite being stable in their duplex form, the stability of the siRNA duplex can be increased by chemical modification and reduced off-target effects and help target siRNAs into the cell or tissue. A backbone modification is included in incorporating phosphodiester or ribose units. Modifications of RNA at the 2'-position of the ribose ring increase the stability of the siRNA, preventing nuclease access to the active site and decreasing immune activation. This is because the resulting molecule has increased resistance to nucleases and an increased half-life in vivo. Not only are the chemical bond modified, but the sugar unit can be modified as in 2'-fluoro (2'-F), 2'-O-fluoro-β-D-arabinonucleotide (FANA) and 2'-O-(2-methoxyethyl) (MOE) as well as during the synthesis of modified RNA nucleotides called locked nucleic acid (LNA). Additionally, the 2-O-methyl modification in the seed hexamers of the guide strand can also reduce off-target effects. Simultaneous insertion of 2-O-methyl group in the passenger strand results in efficient RNAi without any off-target silencing. 2-O-methyl modifications of U or G residues in the passenger strand reduced immune activation but had no negative effect on RNAi. Chemical modification is another technique for improving gene silencing and reducing non-specific off-target effects.

- Bioconjugation

Bioconjugation of RNAi molecules with lipid units or degradable polymers improves RNA delivery and uptake besides stabilizing their thermodynamic and nuclease properties and enhancing RNAi pharmacokinetics. RNAi molecules can be bioconjugated to a specific ligand, e.g. oligonucleotides bioconjugated to folate which targets siRNA/miRNA/shRNA to a specific cell type. Oligonucleotides can be conjugated to cholesterol to increase the net hydrophobicity of oligonucleotides, which allows easy passage through the lipid bilayer and increases cellular uptake and hepatic deposition following i.v. injections. Researchers have also conjugated oligonucleotides to galactose-PEG to increase stability and ensure targeted delivery to hepatocytes in vivo. An acid sensitive ester linkage will ensure cleavage and release of free ODN in the acidic environment of the endosome.

Novel strategies for Delivery of RNAi

- Nanoparticles applied to deliver RNAi molecules

A nanoparticle based on single-walled carbon nanotubes conjugated with piperazine–PEI derivatives was developed by researchers for breast cancer gene therapy. Epithelial cell adhesion molecules, which are overexpressed in solid tumors and recently identified as a cancer stem cell marker, are the targets of the vector–aptamer conjugate, which was designed to improve DNA transfection. Additionally, structural modification (amide bond formation between single-walled carbon nanotubes and PEI) applied in their work has decreased cytotoxicity compared with PEI 25 kDa. A degradable polycationic prodrug called DSS-BEN was synthesized from the polyamine analog N1,N11-bisethylnorspermine and then selectively disassembled in the cytoplasm to release miRNA. An innovative combinatorial therapy was created based on the coordinated regulation of polymer prodrug nanoparticle by researchers. They hypothesized that simultaneous delivery of miR-34a and BENSpm by DSS-BEN/miR-34a nanoparticles would improve the combination antitumor activity. Improved cell killing in vitro and increased tumor growth inhibition in HCT116 xenografts in vivo were observed. A novel nanoparticle formulation based on poly lactic-coglycolic acid (PLGA) for the simultaneous delivery of small amounts of DOX and bcl-xl shRNA was developed. It was shown in vitro that PLGA-DOX-alkyl-PEI/pBcl-xL shRNA with sustained release kinetics caused tumor cell death and inhibited breast cancer cell proliferation better than free DOX and PLGA-DOX-PEI/pBcl-xL shRNA.

- Other carriers applied to transfer RNAi molecules

Viral vectors can provide the most efficient means of delivering the desired genetic material to a cell. Commonly used viral vectors include retroviral, adenoviral, adeno-associated, slow virus, and herpes simplex virus vectors. The benefits of each are unique. By integrating into target cell genomes, retroviral and lentiviral vectors deliver lasting gene expression through one-time administration. Adenoviral vectors transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, but are subject to immunostimulation, limiting their use in vivo. Lastly, adeno-associated virus also transduces both dividing and non-dividing cells, but with low capacity for DNA insertion. Peptides can substitute for liposomes to deliver siRNA to certain cells; histidine-lysine (HK) polymers have been shown to be more effective than liposomes at delivering siRNA to target cells. Lysine of HK polymers can bind to the phosphate backbone of siRNA while histidine acts as a proton pump and causes the release of siRNA in vivo; these two peptides work together to achieve RNAi delivery. In addition, polymers can bind to the adapter body and deliver siRNA to target cells. With biodegradability and variety of permutations, peptides can be used as a nucleic acid carrier.

Conclusion

A number of challenges must be addressed before RNAi may be considered as a therapy. These include delivery of siRNA/shRNA/miRNA systemically and the potential for nonspecifically delivered siRNA/shRNA/miRNA to cause toxicity. Delivery of targeted siRNA/shRNA/miRNA may enhance the therapeutic potential of RNAi. Also, targeted distribution in the cell is important for optimal function. Apart from the barriers to systemic delivery, cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking remains a major barrier for RNAi molecules. The extent of these limitations varies among siRNA, shRNA and miRNA. Unlike siRNA which is targeted to cytoplasm, shRNA expression vector must translocate into the nucleus for transcription into shRNA, which requires nuclear export to cytoplasm and subsequent conversion to siRNA. Thus, cellular trafficking remains a major barrier, especially for shRNA and externally added miRNAs. Despite this limitation, shRNA is promising option since it provides persistent and stable gene silencing if viral vectors are used. In addition, they can be produced in large quantities.

References

- Svoboda, Petr. "Key mechanistic principles and considerations concerning RNA interference." Frontiers in Plant Science 11 (2020): 1237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01237.

- Unniyampurath, Unnikrishnan, Rajendra Pilankatta, and Manoj N. Krishnan. "RNA interference in the age of CRISPR: will CRISPR interfere with RNAi?." International journal of molecular sciences 17.3 (2016): 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030291.

- Isenmann, Marie, et al. "Basic principles of RNA interference: nucleic acid types and in vitro intracellular delivery methods." Micromachines 14.7 (2023): 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14071321.

- Liu, Zehua, et al. "Non-viral nanoparticles for RNA interference: Principles of design and practical guidelines." Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 174 (2021): 576-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.018.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.