siRNA-The Precision Guided Missiles of Gene Silencing

What is the siRNA

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a short nucleotide sequence, about 20-30 nucleotides long. It was first discovered and used in molecular biology for gene silencing via the RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. Development of siRNA began in the late 1990s and since then has become one of the most promising tools in gene function analysis and therapy. A small interfering RNA is a short fragment of RNA which is complementary to the mRNA and inhibits expression of a particular gene. It provides a very specific and accurate control over gene expression. It is also used for gene silencing of disease-causing genes, so siRNA has great potential for therapy development. Unlike other small molecule drugs or monoclonal antibodies, it does not interact with DNA. The process is guided by Watson-Crick base pairing. As such, the specificity of siRNA allows researchers to create drugs that have no or negligible side effects on other tissues or organs. Therefore, siRNA is also a great candidate for those genes which are difficult to address using other means, e.g. oncogenes in cancers, viral genes in virus-related diseases, and mutated genes in certain genetic disorders.

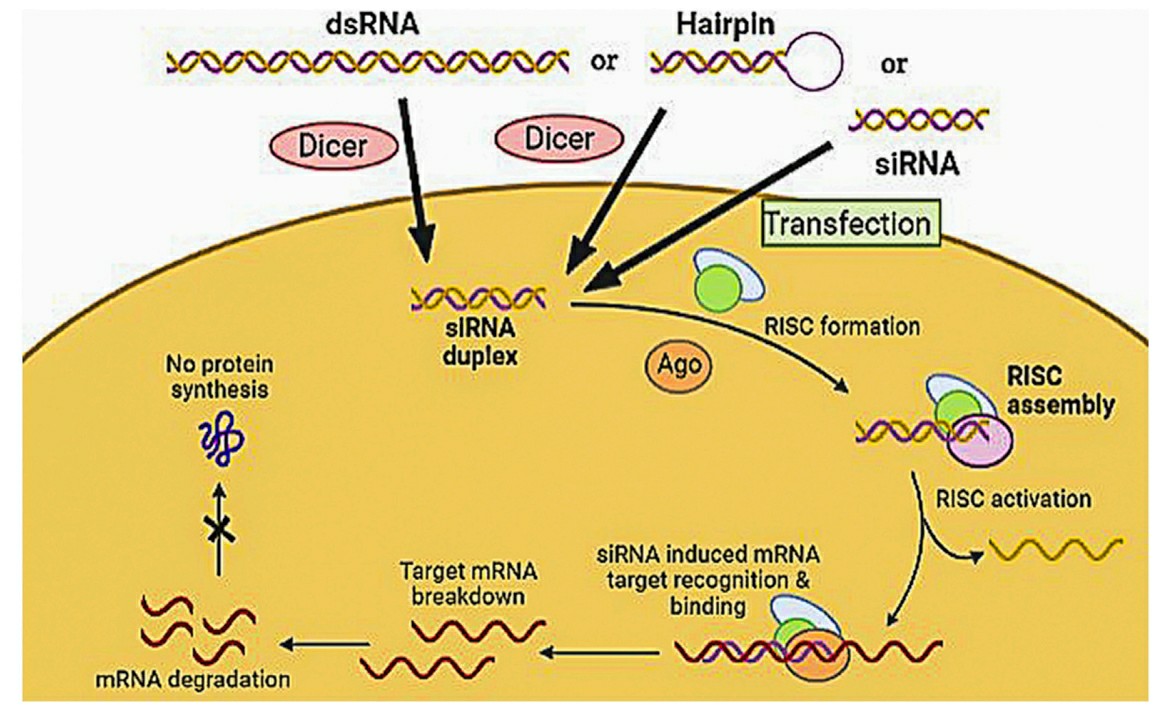

Mechanism of siRNA

The siRNA is a double-stranded RNA molecule that has a size range of 21-23 nucleotides and acts post-transcriptionally. It forms a duplex from long dsRNA by cleavage of Dicer, a protein from the RNAse III family. The duplex formed consists of a sense (passenger) and an antisense (guide) strand. siRNA is then loaded into RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and interacts with its Argouate 2 (Ago2) component and the passenger strand of siRNA is degraded. The remaining strand (guide) then interacts with the target mRNA, guiding the RISC to the mRNA. To ensure that this process leads to effective silencing of a target gene, siRNA must be correctly loaded onto RISC. siRNA of greater than 30 nucleotides may lead to induction of interferon and immune reactions through activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs), causing global silencing of genes and cell death. siRNA can also cause side effects through silencing of non-target mRNAs that have partial homology with the target mRNA. This causes a downregulation of non-target genes which leads to issues in data analysis and toxicity. The lowest concentration at which a specific siRNA causes effective silencing of a target gene must be determined.

Fig. 1 Mechanism of siRNA by assembly and activation of RNA- RISC1,5.

Fig. 1 Mechanism of siRNA by assembly and activation of RNA- RISC1,5.

Design and Synthesis of siRNA

- Design Principles

The initial step in designing an siRNA is the identification of the target site in the mRNA of interest. Typically effective target sites will be 19-21 nucleotides long and begin with an AA dinucleotide. This is based on the observation that siRNAs with 3' overhanging UU dinucleotides are the most active. It is recommended to identify 2-4 target sequences to increase the chance of obtaining significant gene knockdown. siRNAs with 30-50% GC content tend to be more active than those with higher GC content. Avoid long stretches of more than 4 T's or A's in the target sequence as they can be recognized as termination sites by RNA polymerase III. Use BLAST to compare the potential target sites to the relevant genome database to eliminate sequences that have significant homology to coding sequences. The siRNA sequence should be designed taking into account its thermodynamic properties in order to allow for a better binding of the antisense strand to the target mRNA. The siRNA sequence should not contain single nucleotides in a row and reverse repeat sequences to avoid non-specific binding and make the siRNA more stable. Design siRNA sequences with a 3' overhang of UU to increase the stability of the siRNA duplex.

- Synthesis Methods

Solid-phase synthesis is the most commonly used approach for the synthesis of synthetic siRNA. RNA synthesis is a cyclic chemical reaction in which each nucleotide is added on a solid support. The process involves a deprotection step to remove the protecting group from 5'-hydroxyl of the solid support bound nucleotide. The generated 5'-hydroxyl is coupled with an activated 3'-phosphorous ester and capping step is used to remove the unreacted nucleotides from the reaction system. Intermediate goes through another step to oxidize phosphite to phosphorous ester. After the chain assembly, the oligomer is released from the solid support, deprotected, and purified by HPLC. Two kinds of building blocks were designed for the efficient synthesis of RNA including 2'-O-TOM and 2'-O-ACE modified nucleotides. Both methods give a coupling yield of over 99%. The whole process was automated by using oligonucleotide synthesizers.

siRNA Design Considerations

SiRNA-mediated silencing has three features that make it a desirable therapy; it acts post-transcriptionally, the knockdown is highly specific, and the same mRNA target can be inhibited by many different siRNA sequences. Since siRNA sequences can have very different activities, considerable effort has been made to identify factors that enhance siRNA activity and suppress off-targeting and nonspecific effects. These features can be broadly classified into two groups, those affecting siRNA activity and those affecting siRNA specificity. siRNA activity is influenced by, amongst other things, strand selection, the structure of the target region, base preferences and overall siRNA G/C content. siRNA specificity is dependent on strand selection, immunogenicity and uniqueness of the target sequence.

- Differential Terminal Hybridization Stability

The differential recognition of the termini of the siRNAs by the RLC proteins can cause the siRNA to become incorporated into the complex in a biased manner. Asymmetry and biased strand loading of siRNAs were found early to be associated with differential terminal hybridization stability (the difference in hybridization free energy between the two ends of the siRNA). Studies based on functional asymmetry and biased strand loading determined that the strand whose 5' end was less stably hybridized (higher hybridization free energy) to the complementary strand was preferentially loaded into RISC. The calculation of differential hybridization stabilities initially used the four terminal base pairs at each end of the siRNA. However, more recent research indicates that one nearest neighbor provides a more predictive calculation. When choosing siRNAs, it is best to eliminate those siRNAs with an unfavorable differential stability.

- 5' Nucleotide Preference

Some nucleotide positions within the siRNA have been shown to correlate with siRNA activity. Of these, the strongest positional preference is for the nucleotides at or near the 5' termini of the siRNA strands. Although there is some debate over what nucleotides have the most predictive value, there is also no well-supported biological explanation for why certain nucleotides preferentially pair with each other. The only clearly determined factor is that of the 5' termini. Specifically, a "nucleotide specificity loop" was found on Ago2 which prefers pairing with U and A nucleotides and has a much weaker preference for C and G nucleotides. After classification of the siRNA strands by their 5' termini, this pool of candidates can be further narrowed down to those that contain the nucleotides that confer the highest probability of high activity.

- mRNA Target Region

Secondary structure of mRNA prevents siRNA binding through steric hindrance of RISC binding and cleavage. Conveniently, mRNA secondary structure can be predicted in silico, and approximately accurately, using the nearest neighbor algorithm to predict the most thermodynamically stable structures. If more certainty about the structure is required, experimental structural analyses can be used to refine the predicted structures. However, in a living cell the mRNA structure is dynamic and any prediction will only be approximate and will only serve to guide a choice of potential target regions. With this information, it is suggested that, when a choice exists, the most accessible regions should be targeted, particularly those at the 5' and 3' ends of the target region.

- Immunogenicity

SiRNAs can induce various immunogenic and cytotoxic reactions, some of which are due to their dsRNA structure and others which are sequence-specific. Immune receptors for siRNAs are located on the cell surface, in endocytotic vesicles, and in the cytosol. The siRNA can be prevented from interacting with cell surface and endosomal receptors by protection/inhibition of access to the siRNA using a delivery vehicle, but it is still advantageous to design siRNAs that do not use immunostimulatory sequence motifs recognized by these receptors. Cytosolic receptors for RNA are present in the same abundance in all cell types and recognize primarily structural features rather than sequence motifs. The OAS1, PKR, and RIG-I receptors are examples of these. The canonical siRNA structure does not induce PKR or RIG-1; these receptors respond to dsRNA longer than 30 bp or having 5'-triphosphates. Unlike PKR and RIG-1, OAS1 is also activated by a sequence motif (NNWW(N9)WGN) in dsRNA as short as 19bp. To avoid immunostimulatory motifs when designing an siRNA the immunostimulatory motifs to avoid are GUCCUUCAA, UGUGU, UGU, UCA, GU-rich sequences, AU-rich sequences, and U-rich sequences. In addition to the immunostimulatory sequences, the UGGC motif has been shown to be cytotoxic through non-immune mechanisms.

- Incorporation of Chemical Modifications

Stabilizing modifications in siRNAs increase the chemical resistance (to nucleases), decrease immunogenicity and improve siRNA activity to the best extent possible. Phosphodiester backbone, ribose sugar, nucleotide bases and the 2'-OH group of ribose can be chemically modified. Successful chemical modification involves substituting a new chemical moiety for an existing one at a specific position in the siRNA so that the added group or modified structure will not affect the function of siRNA. Chemical modifications are generally small changes to the siRNA structure intended to disrupt recognition and binding of the siRNA by nucleases and RNA receptors. Common chemical modifications are 2'-O-methyl or 2'-F of the 2'-OH group of ribose, which prevent recognition of RNA by nucleases and TLR7 and TLR8. The 3' overhangs are another common site for chemical modification because they may serve as a target for endoribonucleases and because chemical modifications, even bulky ones, are well tolerated at this position.

Applications of siRNA in Disease Therapy

- Cancer Therapy

SiRNA has the potential to target oncogenes and cancer associated signaling pathways. Examples of targeted oncogenes include c-Myc, RAS, and Bcl-2. These are often over-expressed in several types of cancer and when downregulated by siRNA, this results in tumor growth inhibition, apoptosis and prevention of metastasis. For example, siRNA targeting the oncogene KRAS has been shown to be effective in an NSCLC xenograft model using EGFR mediated delivery. Additionally, siRNA can target cancer associated signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and immune evasion. Examples of targeted signaling pathways include EphA2 oncoprotein, which has shown a substantial downregulation of EphA2 expression in a xenograft ovarian cancer model.

- Other Diseases

SiRNA is not only used for the treatment of cancer, it also has the potential to be used in the treatment of respiratory and ocular diseases. Many siRNA drugs are currently in clinical trials for these diseases. One example of this is the targeting of the VEGF pathway for age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is the leading cause of blindness. In respiratory diseases, siRNA is being tested in treatment of viral infections and inflammatory processes. One example of this is the targeting of the influenza virus in preclinical studies. Finally, siRNA-based therapeutics are being developed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis targeting genes for inflammation and mucus.

- Challenges: Efficient Delivery Systems and Minimizing Immune Activation

However, the application of siRNA in clinical practice is still challenging due to many issues. A key issue is to develop effective delivery system that can protect siRNA from nuclease degradation and target specific cell types for endocytosis. Neutral, anionic and cationic liposomes can increase siRNA stability and cellular uptake. Neutral, anionic and cationic liposomes have also been used to increase siRNA stability and cellular uptake. For example, neutral liposomes formed by 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC) has been used to deliver siRNA against oncoprotein EphA2 and was found to produce significant tumor regression in the mouse model of ovarian cancer. siRNA, when activated by innate immunity, also interacts with TLRs to induce pro-inflammatory cytokines. The scientists have been devising means to protect siRNA by chemical modification or immune-evasive delivery systems. For example, protamine, a small arginine-rich protein, can protect siRNA from degradation and down-regulate the immune activation.

References

- Thakur, Shikha, et al. "A perspective on oligonucleotide therapy: Approaches to patient customization." Frontiers in Pharmacology 13 (2022): 1006304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1006304.

- Hu, Bo, et al. "Therapeutic siRNA: state of the art." Signal transduction and targeted therapy 5.1 (2020): 101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0207-x.

- Fopase, Rushikesh, et al. "Potential of siRNA in COVID-19 therapy: Emphasis on in silico design and nanoparticles based delivery." Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 11 (2023): 1112755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1112755.

- Chernikov, Ivan V., Valentin V. Vlassov, and Elena L. Chernolovskaya. "Current development of siRNA bioconjugates: from research to the clinic." Frontiers in Pharmacology 10 (2019): 444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00444.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.