RNAi in Genetic Disorders-The Promise of miRNA and siRNA

Introduction of RNAi

The field of RNA interference (RNAi) has been growing rapidly since the first discovery of RNAi in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. RNAi was later shown to occur in mammalian cells in response to the delivery of double-stranded small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of ∼21 nt in length, the effectors of sequence-specific gene silencing. Mechanistic details followed in the subsequent years, and with them, came the growing expectation that RNAi pathways might be exploited to treat genetic diseases. The most attractive aspect of RNAi for therapeutics is the ability to target disease-causing genes of known sequence with high specificity and potency. In addition, the relatively short timescale of testing candidate therapeutic RNAi molecules, and the fact that even newly identified pathogens could be targeted in a timely manner, have fueled a great deal of excitement about the potential to treat a wide range of diseases with RNAi. RNAi pathways are directed by small RNAs, including siRNAs and miRNAs, that are derived from imperfectly paired hairpin RNAs encoded in the genome. RNAi effector molecules induce gene silencing by directing sequence-specific cleavage of perfectly complementary mRNAs and translationally repressing and/or degrading transcript for imperfectly complementary targets.

Introduction of Genetic Disorders

Genetic disorders involve the underlying material that provides instructions for development. There are many mechanisms by which genetic disorders result in neurodevelopmental disabilities. These include disorders caused by the wrong amount of genetic material, missing genetic material, single gene disorders, and mitochondrial disorders that impact the function of genes. The nucleus of each cell contains chromosomes, which are made of the DNA and the genes. Abnormalities of whole chromosomes such as trisomies (having an entire extra chromosome, such as Down syndrome) or duplications, rearrangements and deletions of part of a chromosome (such as Williams syndrome) can have important effects on development at the cellular level. Changes in single genes (such as neurofibromatosis type I) can also interfere with the usual course of development by providing too much, too little, or none of a protein, or by interfering with regulation of expression of other genes. Mitochondrial disorders are a unique set of disorders because they are maternally inherited and are associated with neurodegenerative disease with episodes of crisis during illness or other times of stress.

Recognition of mRNA targets by siRNA and miRNA in vivo

To activate the RNAi machinery, the siRNA must be perfectly complementary to the target mRNA. Binding to this perfectly complementary sequence initiates AGO2 cleavage of the phosphodiester backbone at the 10th and 11th nucleotides downstream from the 5' end of the guide strand. The cleaved mRNA is subsequently digested by exonucleases. For miRNA, target recognition is more complex because there are different binding sites and different levels of complementarity between miRNA and target RNA. This is because, unlike siRNA, miRNA need only be partially complementary to its target mRNA. Because miRNA-mRNA recognition does not have to be perfectly matched, one miRNA strand can recognize a group of mRNAs and miRNA have the property of having multiple targets. Because of the partially complementary base pairing between mRNA and miRNA, AGO2 in the miRISC is not activated. Instead, mRNA targets of miRNA are silenced through translational repression or degradation by deadenylation, decapping or exonuclease activity. On rare occasions, high levels of complementarity between mRNA and miRNA cause endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNA by AGO protein, a process similar to siRNA-mediated gene silencing.

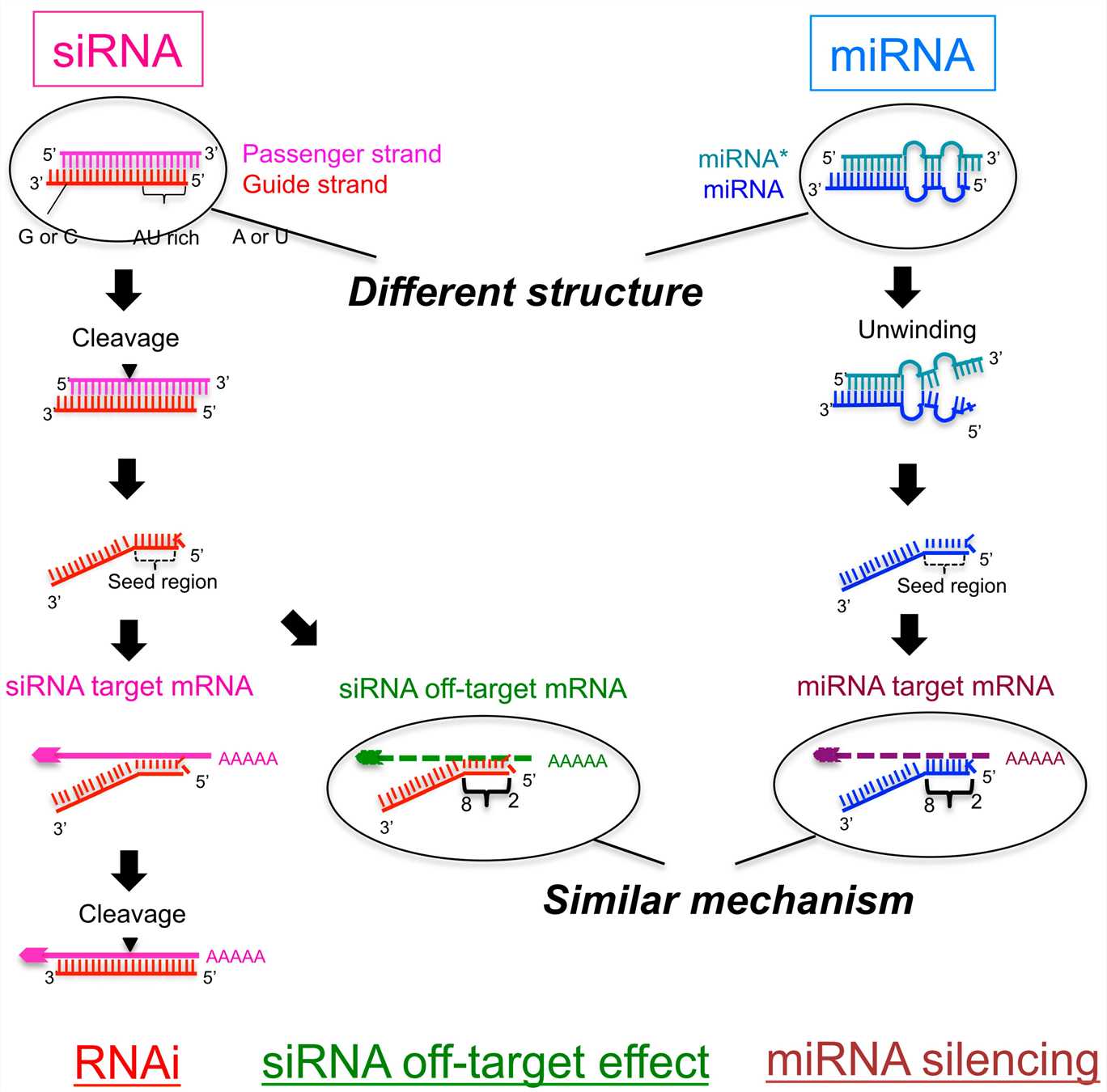

Fig. 1 Schematic figure showing the pathway of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) and microRNA (miRNA)-mediated RNA silencing1,6.

Fig. 1 Schematic figure showing the pathway of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) and microRNA (miRNA)-mediated RNA silencing1,6.

Design of therapeutic siRNA in Genetic Disorders

The first prerequisite for effective siRNA usage is the selection of an active and specific siRNA sequence. A typical siRNA is 19–21 nucleotides in length with two additional nucleotides at the 3' end (TT and UU). These nucleotide overhangs are required for the recognition of the RNAi machinery. In general, increasing the length of the dsRNA will enhance the activity of the siRNA. In one in vitro study, 27 nucleotide long dsRNAs were shown to be as much as 100 times more active than the traditional 21 nucleotide long siRNAs. Longer dsRNAs have to be processed by Dicer to the smaller siRNAs (Dicer-ready or Dicer-substrate siRNAs), which can be more readily loaded into the RISC, leading to the following gene silencing process. The dsRNAs longer than 30 nucleotides in length may activate the IFN pathway and should not be used in therapy.

- Strand selection

For efficient silencing, the siRNA has to be correctly orientated and loaded into the AGO of the RISC for the passenger strand to be cleaved and released, leaving the guide strand complementary to the target mRNA to bind to the active RISC and guide it to the target mRNA. The guide strand of the RNA duplex is determined during the AGO loading step. However, both strands in the RNA duplex may potentially be loaded into the AGO as the guide strand. A mismatch in the loading orientation results in the intended guide strand being released and off-target effects occurring because the remaining strand (the intended passenger strand) base-pairs to the nonintended mRNA. Since this effect occurs for both siRNA and miRNA, the RNA duplex needs to be carefully designed to ensure correct guide strand selection by the RISC. Two parameters for this are known: the asymmetry rule and the 5' nucleotide preference, both of which can be applied to siRNA as well as miRNA design.

- Efficiency affected by G/C content

The effect of the overall G/C content of the siRNA sequence on the overall siRNA activity has been reported but its significance is unclear. The G/C content affects both the overall duplex thermodynamic stability and target site accessibility. It has been shown that siRNAs with a high G/C content (more than 65%) are less active. However, other reports have shown that siRNAs with a G/C content of about 60% are highly active. In general, siRNA should have a G/C content of 30–64%. In addition, sequences containing a stretch of 9 or more nucleotides of G/C should be avoided because they may decrease the gene silencing activity of siRNA.

Design of therapeutic miRNA in Genetic Disorders

SiRNAs are applicable to fewer therapeutic areas compared to miRNAs. The goal of miRNA replacement therapy is to use synthetic miRNAs (miRNA mimics) to replace endogenous miRNAs. To do so, the synthetic miRNAs must be loaded into RISC and then silence target mRNAs via the endogenous miRNA pathway. A single stranded RNA molecule with the same sequence as the guide strand of the mature miRNA is expected to be a functional miRNA mimic. However, the duplex structure of the miRNA has been demonstrated to be 100 to 1,000 times more effective than the single stranded RNA. This is because the double stranded structure can promote the loading of the RNA molecule into the RISC to better perform gene silencing. As a result, designing miRNA mimics with a duplex structure has become the focus of therapeutic development. Synthetic miRNA precursors with longer sequences (a few additional nucleotides to the full-length pri-miRNA) have also been proposed as therapeutic agents. Since pri-miRNAs are processed in the nucleus, but pre-miRNAs and miRNAs are not, distinct methods for delivering different forms of miRNA mimics to their cellular targets are needed. As in siRNAs, viral vectors can be used to express miRNAs within cells.

Delivery of siRNA and miRNA for Genetic Disorders

- Viral vectors

Certain viral vectors have been engineered to express shRNAs or miRNAs to mediate RNAi activity through the mechanism of gene knockdown. Lentiviruses, adenoviruses, and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are most commonly used. All of these are very efficient at delivering the RNA-encoding vector to the nucleus of mammalian cells to express high levels of RNA. Viral vectors are used in over 70% of all gene therapy clinical trials to deliver nucleic acids due to their high transduction efficiency. The viruses used to deliver therapeutic RNA are usually rendered nonvirulent through genetic engineering and tropism can be modified by altering the capsid to target specific cell types. Viruses also provide for long-term expression as they are able to integrate into the host genome (i.e. lentiviruses). Viral vectors do have many safety concerns such as high immunogenicity (especially adenovirus), insertional mutagenesis (especially lentivirus), low packaging capacity (especially AAV), and high production costs.

- Nonviral vectors

Nucleic acids, being negatively charged molecules, can be complexed with cationic polymers via electrostatic interaction. Formation of polyplexes with nucleic acids is simple and nanosized polyplexes allow endocytosis into cells. Polymer molecules that have high proton buffering capacity can also help with endosomal escape of RNA, which prevents degradation of RNA in the endosome/lysosome. Synthetic polyethylenimine (PEI), with a high pH buffering capacity, is one of the first-generation polymers tested for nucleic acid delivery. It is the most extensively studied polymer for siRNA and miRNA delivery in vivo. Because of its high transfection efficiency, PEI is regarded as the gold standard among the nonviral vectors. Other than PEI, dendrimers are highly branched synthetic polymers with well-defined molecular architecture and have also been widely studied for nucleic acid delivery. Dendriplexes are polyplexes formed between dendrimers and nucleic acids. Poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) and polypropylenimine are cationic dendrimers that have been evaluated for RNA delivery in vivo. Due to the high charge density, cationic PEI and dendrimers are often highly toxic which limited their clinical application. To overcome this problem, modified forms of PEI or dendrimers have been developed to improve their delivery efficiency.

miRNA and siRNA in Metabolic Disorders

miRNA as Therapeutic Targets

Since miRNAs target multiple genes associated with pathophysiology, they are an attractive therapeutic target. For example, several miRNAs that are dysregulated have been implicated in diabetes mellitus and its associated aberrant insulin production and glucose homeostasis. MiR-375 is enriched in pancreatic islet cells and controls glucose-induced insulin release. Its overexpression inhibits insulin release while its knockdown leads to hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance. MiR-375 and other dysregulated miRNAs are thus potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

siRNA for Genetic Disease Therapy

- Huntington's disease

There are disease-causing polyglutamine (polyQ) proteins encoded by CAG-repeat containing transcripts that have been identified in Huntington's disease (HD). HD is a progressive, untreatable, neurodegenerative disease caused by a dominant expansion of CAG repeats in the huntingtin gene (HTT). The fact that the CAG repeats also occur in many normal transcripts in normal tissues precludes selective targeting of the disease-causing CAG repeats by siRNA. On the other hand, the diseased region of the brain can be targeted by siRNAs or viral vector-encoded shRNAs.

- Sickle cell anemia

The Glu to Val single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutation of codon 6 (GAG → GTG) of the Hb β-chain gene is the cause of sickle cell anemia (SCA). The HbS, generated by the G to A transition, forms polymers upon deoxygenation to generate long, rigid fibers, which render the red blood cell (RBC) inflexible. SNP-selective RNAi against disease-causing alleles of the human β-globin has been recently described. In this study, researchers constructed allele-specific siRNAs, which were designed to have the SNP of the β-globin mRNA at position 10 of the guide strand of siRNA and were tested for efficacy on an allele-specific luciferase reporter in tissue culture. In vitro studies showed that the βS siRNA suppressed only the βS gene, while having no effect on the expression of the normal βA or β-globin genes. While the βS siRNA was highly specific, the βA siRNA not only suppressed the expression of βA, but also silenced the βS reporter and cDNA construct. The central mismatches with pyrimidine: pyrimidine or pyrimidine:purine residues did not completely block RNAi activity, while mismatches with bulky mismatched purines at position 10 blocked RNAi activity completely, which suggests that mismatches at the mRNA cleavage site involving pyrimidines are not as critical.

References

- Ui-Tei, Kumiko. "Is the efficiency of RNA silencing evolutionarily regulated?." International journal of molecular sciences 17.5 (2016): 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050719.

- Zare, Mina, et al. "Encapsulation of miRNA and siRNA into Nanomaterials for Cancer Therapeutics." Pharmaceutics 14.8 (2022): 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14081620.

- Dzmitruk, Volha, et al. "Dendrimers show promise for siRNA and microRNA therapeutics." Pharmaceutics 10.3 (2018): 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10030126.

- Paccosi, Elena, and Luca Proietti-De-Santis. "Parkinson's disease: from genetics and epigenetics to treatment, a miRNA-based strategy." International journal of molecular sciences 24.11 (2023): 9547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119547.

- Wang, Peipei, Yue Zhou, and Arthur M. Richards. "Effective tools for RNA-derived therapeutics: siRNA interference or miRNA mimicry." Theranostics 11.18 (2021): 8771. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.62642.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.