RNAi Therapeutics in Action-Delivery, Diseases, and Clinical Frontiers

Barriers in delivery of shRNAs, miRNAs and siRNAs

Transport of RNA interference (RNAi) molecules, including shRNAs, miRNAs, and siRNAs,in vivo is difficult due to their physicochemical characteristics and multiple biological barriers. The prime goal is to protect RNAs and maintain their stability from the point of entry to the target and cross through the cell membrane by avoiding degradation by enzymatic activity. SiRNA is a hydrophilic and negatively charged, and thus have low permeability across the membrane. Both the charge and large size make diffusion through the intestinal layer difficult. In order to overcome these barriers, conjugation of RNAs with bioactive and biocompatible molecules and synthesis of hydrophobic siRNA have been successfully reported.

- Enzymatic degradation as a barrier for RNAi-based therapeutics

Biological compounds are degraded by proteases in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Nucleic acid (NA) compounds like siRNAs, are degraded by nucleases. Nuclease is a class of enzyme involved in DNA repair, DNA replication, base excision repair, and mismatch repair mechanism. Nuclease enzyme is also capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bond of nucleic acid. Nuclease and nucleosidases are NA-degrading enzyme secreted from the pancreas. It was observed in a study that plasmid DNA is completely degraded in diluted GI fluid. So, to prevent the breakdown, the physicochemical characteristics of siRNA must be altered, or it must be delivered with a carrier which can prevent the degradation by nuclease enzyme. For example, siRNA was modified with 2'-flouro (2'-F) pyrimidines to increase the plasma half-life of siRNA in mice plasma. Another study found that 2'-O-MOE-modified NAs were stable in rat duodenum for at least 8 h; however, the plasma concentration was only 0.3 to 5.5% compared to intravenous administration.

- Barriers for cellular internalization

One of the obstacles that siRNA molecule faces is the absorption by intestinal epithelium and access to circulation. Brush border of the intestine has a large amount of polar carbohydrates and charged amino acid side chains that provides a high negative charge to the microvilli at the enterocytes. Since siRNA is also negatively charged, the enterocyte repulses the siRNA molecule, which makes it difficult for the siRNA to attach with the cell. If siRNA gets through the repulsion, the hydrophilic property of it permeates the lipophilic phospholipid bilayer of enterocytes. After going through all those obstacles, nucleic acid reaches the intestinal epithelium. There are four general pathways used to facilitate the absorption: transcellular pathway (through epithelial cells), paracellular pathway (between adjacent cells), transcytosis and endocytosis, and lymphatic absorption through M-cells of Peyer's patches. siRNA-based therapeutics<5 kDa can be transferred through paracellular pathway, whereas if the mass is more than that, then endocytosis is the only way. In the endocytosis process, cells engulf the molecule and form endosome, and the molecule is delivered via endosome to the lysosome for degradation with lysosomal enzyme. After that, it goes to the Golgi apparatus for processing, or some of it goes back to the plasma membrane.

Delivery Platforms for RNAi technologies: From Bench to Bedside

Viral Vectors: The Workhorses of RNAi

- AAV

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have become an attractive delivery platform for RNAi, given their safety and ability to provide long-term gene expression. AAVs are non-pathogenic and low immunogenic and therefore may be applicable to a variety of disease indications. One major area of improvement in AAV technology is capsid engineering, which alters the coat of the virus to increase tissue tropism and efficiency of delivery. For example, AAV9 was engineered to target the central nervous system (CNS), providing a powerful tool for CNS diseases. AAVs have been modified using the TRACER platform to find AAV variants with dramatically increased CNS transduction efficiency.

- Lentivirus

Another powerful technique in delivering siRNA for RNAi is the lentiviral vector, which integrates into the host genome and provides a stable and long-lasting gene expression. This has benefits for RNAi applications requiring long-lasting RNAi effects such as gene therapy of chronic diseases. The major disadvantage of the lentiviral vector is that it can integrate into the host genome and cause insertional mutagenesis. Thus, some safety concerns arise. SIN lentiviral vectors have been engineered, which lack the integrated viral promoter. After the integration, the promoter will be inactivated and will not lead to insertional mutagenesis.

- Baculovirus

Baculoviruses have historically been used for recombinant protein production in insect cell lines. They may also be useful as a vehicle for RNAi based technologies due to their large genomes, allowing multiple genes or large RNAi constructs to be packaged into the viral particles. Mammalian cells have been shown to be transduced with baculoviruses with high efficiency and to express genes, albeit for a short period of time, and with a non-replicating genome. Baculoviruses could be used for high-capacity delivery applications such as RNAi library delivery for high-throughput screening.

- Non-Viral Nanocarriers

The most commonly used carriers of RNAi are nanoparticles. Unlike viral vectors that carry non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) as a viral genome, non-viral carriers provide native ncRNAs. To administer ncRNAs systemically and allow them to traverse physiologic barriers, delivery systems need to be designed to provide serum stability, high structural and functional tenability, minimize interactions with non-target cells, facilitate cell entry and endosome escape, minimize renal clearance, and generate low toxicity and immunogenicity. Various materials have been investigated to address in vivo delivery challenges, and some successful systems have been rationally designed or discovered by high-throughput screens. These systems can be categorized according to their composition into lipid-based and polymer-based systems.

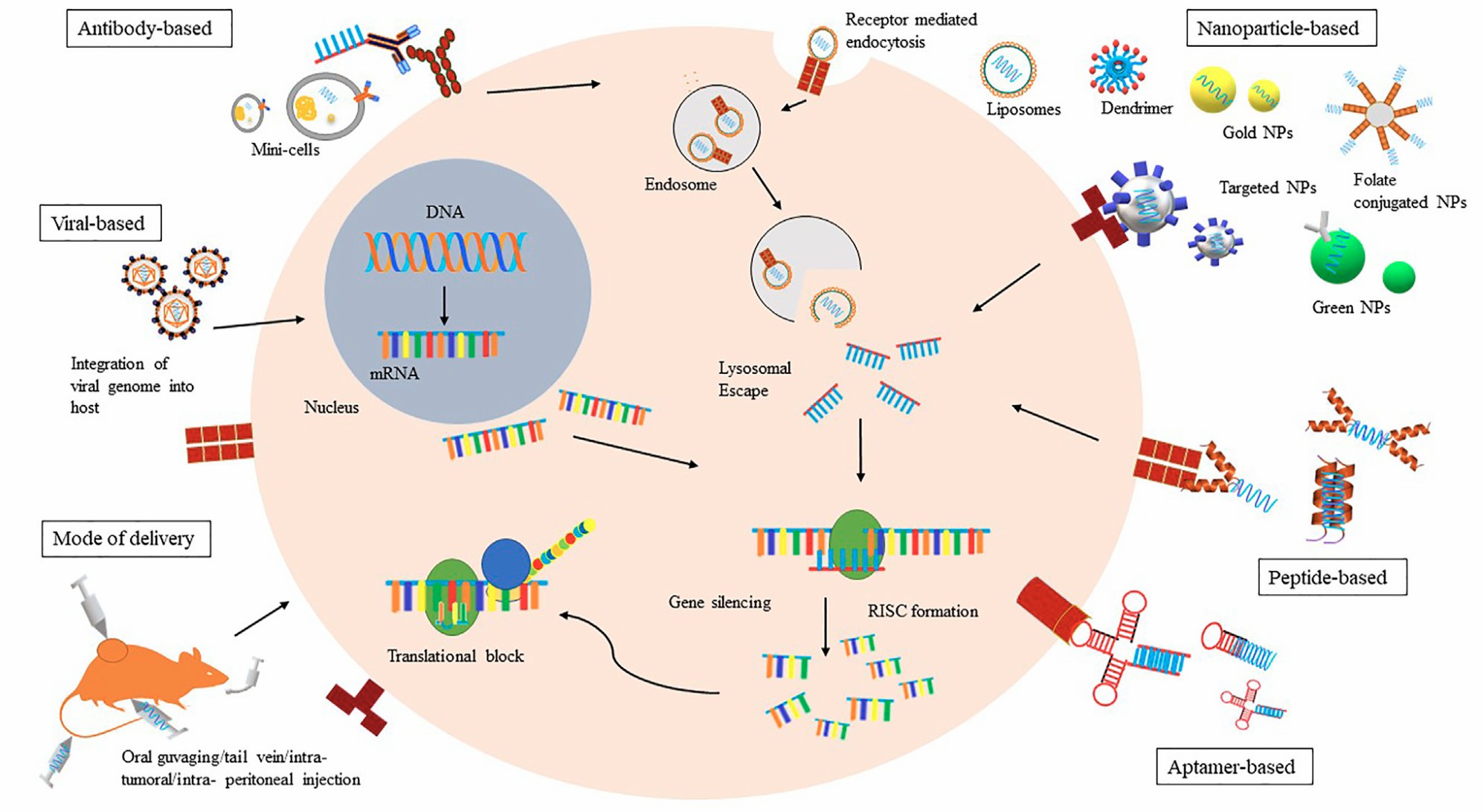

Fig. 1 A schematic representation of various modes of Bio-drug delivery.1,6

Fig. 1 A schematic representation of various modes of Bio-drug delivery.1,6

- Liposomes

Liposomes are artificial vesicles that have a bilayer lipid membrane surrounding an aqueous core, which can form complexes with anionic siRNAs and negatively charged polycations (i.e., "lipoplexes") which are compatible with the cell and simple to manufacture. To achieve sustained release of the material, SLNs are used for RNAi delivery, where siRNA is embedded within SLNs. In a recent study, paclitaxel and human MCL1-specific siRNA (siMCL1) were encapsulated in SLNs. The co-delivery of paclitaxel and siMCL1 showed enhanced anticancer effect on human epithelial carcinoma cell line KB in vitro compared with either paclitaxel or siMCL1 alone.

- Polymer-based nanoparticles

Another widely studied delivery system for siRNA is polymer-based nanoparticles. Negatively charged nucleic acids, including siRNA, readily form complexes with cationic polymers (polyplexes). DNA binding proteins and polypeptides along with synthetic cationic polymers polyethylenimine and chitosan function as carriers in delivery systems. Chitosan is a biocompatible, biodegradable and low immunogenic cationic polysaccharide. Naked chitosan has poor compatibility with biological fluids, and the nanoparticle will be degraded in blood, thereby lowering the working efficiency. The structure should be modified. PEGylated chitosan polyplexes has distinct endocytosis and macrophage phagocytosis and less nonspecific interaction with red blood cells. Polypeptide modified chitosan has higher working efficiency and more endosomal escape. Chitosan nanoparticle conjugated with antibody can target to the specific cells. In a recent study, transferrin antibody and bradykinin B2 antibody were chemically conjugated with chitosan polyplexes, which was able to pass through blood brain barrier to target cells, and enhanced gene silencing efficiency in astrocytes.

- Exosomes

Exosomes (approximately 40–120 nm in diameterhave also been investigated as a natural nanocarrier for nucleotides and chemical drugs. Exosomes are the smallest of the extracellular vesicles. After fusion with the plasma membrane, exosomes are released from the cell. Exosomes carry a series of cell-specific transmembrane proteins that can guide exosomes to the target cells. After reaching the target cell, the exosomal content is released into the cytoplasm and the content changes the intracellular compartment of the target cell. Accumulating evidence has shown that exosomes are a better choice for transporting genetic materials between cells in a natural pathway. Exosomes have several advantages as a natural nanocarrier: suitable for carrying soluble drugs, with high penetration ability, low off-target effects, and low immunogenicity. Exosomes can be loaded with miRNAs and siRNAs through different loading methods. Briefly, through a special treatment of donor cells, synthetic miRNAs or exogenous RNAs can be introduced into exosomes. For example, after loading exosomes with let-7a miRNA with the GE11 peptide on the surface, which can specifically combine with EGFR, let-7a miRNA can be specifically delivered to breast cancer tissues.

Therapeutic Frontiers of RNAi

- Metabolic treatment

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is a regulator of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). The siRNAs targeting PCSK9 decreased LDL-C levels. Liver-targeted siRNAs delivered by nanoliposome or other delivery system can specifically inhibit PCSK9 expression in hepatocytes. This method has shown positive effects in vivo and may be a potential therapeutic method for hypercholesterolemia. miRNAs can regulate the function and metabolism of adipose tissue. Certain miRNAs such as miR-196a can induce the process of white adipose tissue browning. Adipose tissue was considered to be thermogenic and might increase energy expenditure and have beneficial effects on metabolism. miRNAs that reprogram white adipocytes to brown adipocytes inducing adipocyte differentiation and thermogenesis-associated genes have been proposed as a new treatment option for obesity and metabolic disease. Gut-brain axis is associated with the regulation of metabolism and energy homeostasis. Some metabolic genes in the gut can be targeted by oral siRNA formulations and regulate the metabolic process. siRNAs can be incorporated into nanoparticles or other delivery systems to protect the siRNAs and deliver them to the gut. This may be a potential way to treat metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes and obesity via some of the genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism.

- Treatment of neurodegenerative disease

The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) is impermeable to most circulating blood components. Angiopep-2, a small peptide, was found to bind to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1). The Angiopep-2 may be used to coat nanoparticles to aid in passing through the BBB. It can be used to transport RNAi molecules such as siRNAs and shRNAs targeting genes that are responsible for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. miRNAs are involved in the processes of synaptic plasticity and neuroplasticity, which are major processes that regulate learning and memory. miRNAs such as miR-132 and miR-212 target genes that control synaptic function and plasticity. They can target genes that play roles in synaptic transmission and structural remodeling. The method can be used to express these miRNAs to promote neuroplasticity and treat neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive disorders. Astrocytes and microglia are two types of glial cells. It has been found that shRNA targeting glial genes can convert glial cells into neuronal phenotype. The method can be used to treat spinal cord injury and neurodegenerative diseases by making neuronal tissues to replace damaged neurons

- Treatment of infectious diseases

The host's miRNAs have been harnessed for anti-viral treatment. One miRNA-based strategy to render the host resistant to the pathogen's use of the host's miRNAs is possible. The EV-71 virus increases the expression of miRNA-146a in the cell, to suppress an innate immune response. Inhibition of miR-146a expression in mice infected with EV-71, with an intraperitoneal injection of a miR-146a antagomiR, led to improved survival rates from 25% to 80% by inducing an interferon gamma response. Bacterial infections could also be treated with miRNAs. S. enterica infection in mice promoted S. enterica through miR-128 overexpression and intragastric anti-miR-128 treatment blocked this infection effect and reversed it. Researchers found that delivering miR-146a or miR-155 through intraperitoneal exosome administration significantly improved mice's inflammatory reaction to endotoxin and suggested these treatments could serve as promising add-ons in sepsis treatment or vaccination strategies.

- Cancer treatment

One of the main cancer suppressor gene is the guardian of the genome, p53, which is inactivated by point mutations in more than 50% of human cancers. Use of siRNA has suppressed expression of mutated p53, restoring the wild-type gene. In general, programmed cell death (apoptosis) is often aberrantly regulated in most cancers, especially drug-resistant tumors. Cancerous cell apoptosis may be induced by using siRNA to target anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-2, survivin and Akt1. Apoptosis has been induced or chemotherapeutic drugs have been sensitized in various cancers by silencing these anti-apoptotic genes by siRNAs. Survivin is of particular interest, because it is only present in foetal tissue or cancerous tissue and not present in adult tissues. Therefore, suppression of survivin by siRNA may be a tumor-specific therapy without harming normal tissues.

Safety and Specificity Challenges

- Navigation through the Minefield of Regulatory Networks

miRNAs are a part of gene expression regulatory networks. As miRNAs can regulate a large number of genes, miRNAs are being used as therapeutic molecules. However, miRNA mimics are creating further complexity. miRNA mimics increase the expression of endogenous miRNAs and target a multitude of genes that cause off-target effects. miR-34a causes apoptosis and represses oncogenic activity, targeting several genes associated with cell cycle and metastasis. The number of genes that are regulated causes off-target events that interfere with regular cellular processes or even exacerbate conditions. To navigate through the regulatory network, one needs to understand the miRNA regulatory network and develop strategies to improve specificity.

- Therapeutic siRNAs Hijack RISC to Interact with Endogenous miRNAs

SiRNAs are designed to target a gene by binding to complementary mRNA sequences. Although siRNAs are designed to target a specific gene, siRNAs use the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) hijack and bind to endogenous miRNAs. The siRNAs binding to endogenous miRNAs results in off-target events. These off-target events occur when siRNAs cause knockdown in genes other than the one they are designed to target. For example, siRNAs with high seed-region binding energy can knockdown many genes with off-target gene regulation even if modified with chemical groups to lower off-target events. Off-target events must be minimized to prevent unsafe and ineffective siRNA therapeutics.

- shRNA Induces Insertional Mutagenesis

shRNAs are intended to be integrated into the host genome to provide long term knockdown. However, shRNA increases the likelihood of insertional mutagenesis. Because the shRNA construct is integrated into the host genome, the construct can target and disable endogenous genes or regulatory elements and produce genetic mutations. This can be particularly dangerous for therapeutic shRNAs that require long term expression. To avoid insertional mutagenesis, one needs to design safer shRNAs and employ other means of integration.

Future Frontiers

Personalized RNAi-based therapeutics are promising, since they can address complex diseases and diseases that do not have one major driver. Analysis of miRNA signatures in each patient allows the researcher to obtain a unique set of miRNA that causes disease. The unique set of miRNA for a given patient can be used to design siRNA molecules targeting the miRNA that causes the disease. Bespoke siRNA means designing siRNA that matches the genetics and molecules of each patient. Thus, RNAi therapy is improved in terms of targeting and safety because there is less off-targeting and more targeted miRNA that can cause disease. Bespoke siRNA can be used in patients with a high degree of genetic variation, such as in cancer.

References

- Swaminathan, Guruprasadh, et al. "RNA interference and nanotechnology: A promising alliance for next generation cancer therapeutics." Frontiers in Nanotechnology 3 (2021): 694838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2021.694838.

- Mainini, Francesco, and Michael R. Eccles. "Lipid and polymer-based nanoparticle siRNA delivery systems for cancer therapy." Molecules 25.11 (2020): 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25112692.

- Schuster, Susan, Pascal Miesen, and Ronald P. van Rij. "Antiviral RNAi in insects and mammals: parallels and differences." Viruses 11.5 (2019): 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11050448.

- Ali Zaidi, Syed Saqib, et al. "Engineering siRNA therapeutics: challenges and strategies." Journal of Nanobiotechnology 21.1 (2023): 381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02147-z.

- Qiu, Yingshan, et al. "Delivery of RNAi therapeutics to the airways—from bench to bedside." Molecules 21.9 (2016): 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091249.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.