RNAi in Gastrointestinal Diseases-siRNA and shRNA in Gastroenterology

Introduction of RNAi in Gastrointestinal Diseases

RNA interference (RNAi) is a therapeutic modality to knock down a specific gene expression. This is being studied as a therapeutic option for Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. Most GI diseases including IBD, celiac disease, and esophageal scarring are multifactorial diseases, with a variety of genetic and environmental factors contributing to the pathology. Because of the wide range of GI symptoms and the non-specificity of the current therapies, it is difficult to treat GI diseases. RNAi-mediated knockdown of the genes using small interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) is more targeted and effective in treating a particular gene that is involved in the pathophysiology of the disease. For instance, in GI diseases, siRNA could target a specific gene involved in the pathophysiology of the disease, for instance, inflammation, fibrosis, etc. For example, siRNA that targets TNF-α is effective in reducing inflammation in animal models of IBD. In comparison, shRNA is a long-term knockdown method because it integrates into the host genome. As such, shRNA is suitable for long-term target gene silencing for certain conditions. The constructs can be delivered with a viral vector to assure continuous and prolonged silencing effect.

Therapeutic strategies for Gastrointestinal Diseases

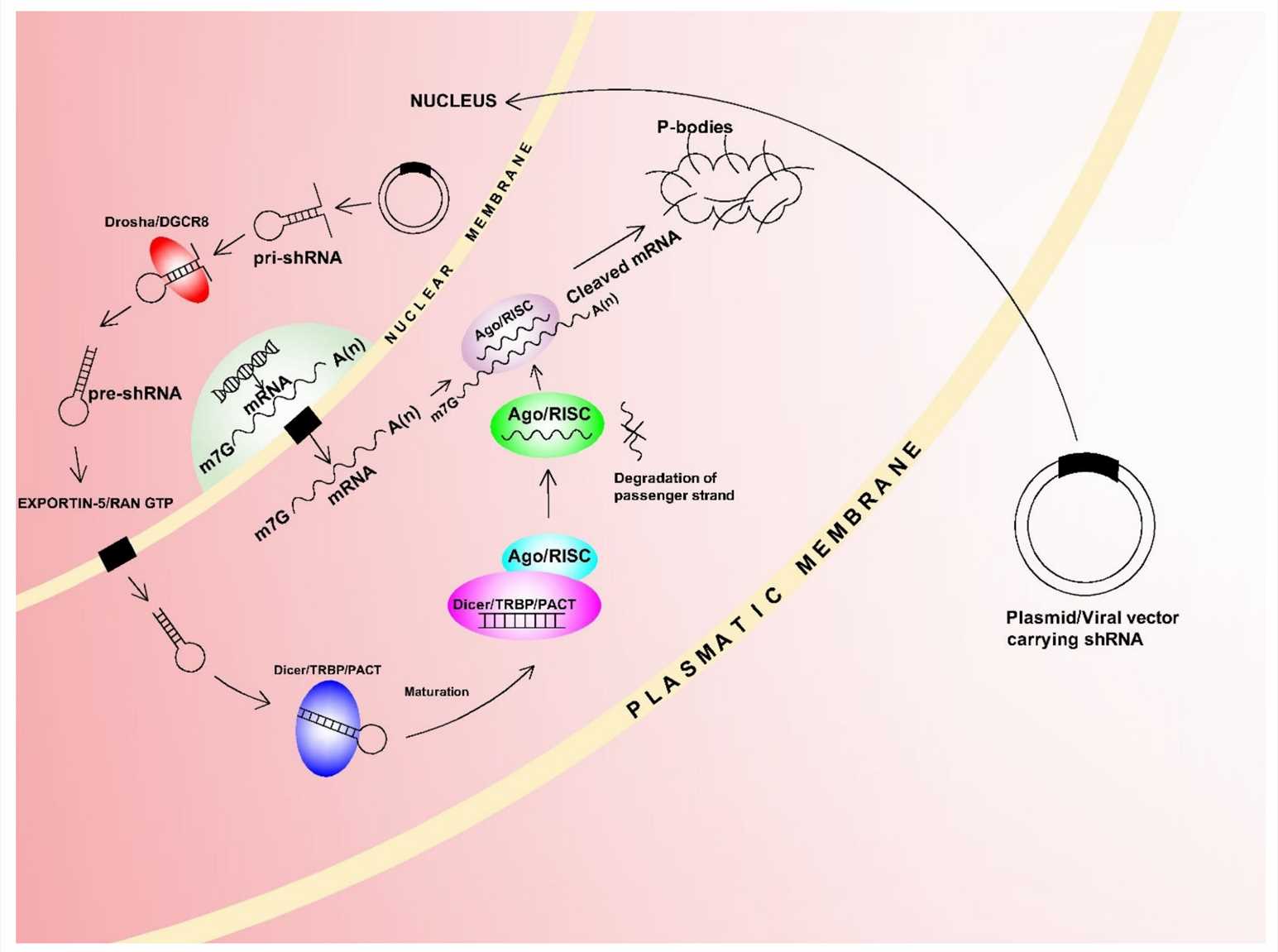

shRNA is a synthetic RNA with a short hairpin secondary structure. Because shRNA is delivered as a DNA plasmid rather than as a double stranded RNA (such as siRNA), it can be expressed for months or years. Once transcribed, the product is processed to form a pri-microRNA. The pri-microRNA is processed to form pre-shRNA and is exported out of the nucleus via Exportin 5. Then, the pre-shRNA is processed to Dicer and binds to RISC complex. Passenger strand is degraded, and the anti-sense guide strand guides RISC to the degradation of the complementary target mRNA. The majority of the GI RNAi therapies explored so far are based on synthetic siRNAs or antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) delivered naked, conjugated to cholesterol, or lipofectamine. These drugs have to be dosed frequently, with unwanted off target effects, and lead to renal and hepatic toxicity.

Fig. 1 shRNA mechanism action1,5.

Fig. 1 shRNA mechanism action1,5.

Off-target effects (OTEs): shRNA vs siRNA

As with off-target effects, the accuracy of shRNA compared to siRNA is uncertain. Several reports suggest that siRNA has more off-target effects (OTEs) than shRNA when compared head-to-head. HCT-116 carcinoma cells were treated with either an siRNA duplex or an inducible shRNA targeting the same 21-mer core sequence of TP53 and microarray hybridization of the cells after 24 h of treatment showed a much greater proportion of off-target genes upregulated or downregulated by siRNA compared to shRNA. The amount of on-target knockdown was similar. The shRNA was compared to siRNA at several concentrations and the authors used a cell line stably expressing their constructs to control for transfection efficiency differences. These experiments confirmed previous work showing greater knockdown by shRNA and fewer off-target effects (For CDKN1A, 470 transcripts downregulated by siRNA vs. by shRNA, of which two were shared). In both lentivirus-transduced or expressed from a stable inducible cell line, shRNA showed much less OTEs than transfected siRNA with the same 19-mer core sequence. Titrating lower concentrations of siRNA could not achieve the same signal to noise ratio as shRNA. They used a single promoter-attempts using promoters of different strengths may give more control over the system.

Delivery for RNAi applications in Gastrointestinal Diseases

siRNA: The Formulation Challenge

- Beyond LNPs: Polymer-Based Delivery Platforms

Delivery of siRNA to the GI tract is particularly difficult because of the extreme conditions in the intestines, which can degrade siRNA before it gets to the target. Polymer-based delivery platforms have been suggested as an alternative to lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), providing better stability and targeted delivery. Alternative delivery systems to LNP-based systems have been proposed such as polymer-based delivery. Polymers are advantageous for delivery systems because they are able to provide greater stability and targeted delivery. siRNA can be protected from degradation and taken up by intestinal cells by encapsulating it with a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer, such as PLGA or PEG. Additionally, siRNA conjugated with certain moieties have been shown to increase siRNA delivery and target specificity. Nanoparticles can also be modified with targeting ligands to improve tissue specificity for the GI tract.

- Conjugation Chemistry: From GalNAc to New Targeting Moieties

GalNAc (N-acetylgalactosamine) conjugates are used to deliver siRNA to hepatocytes via the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR). Conjugation of siRNA with ASGPR has also increased siRNA stability and increased siRNA cellular uptake in liver cells. New targeting moieties are being explored to extend the range of tissues that can be targeted by siRNA therapy. Dynamic polyconjugates (DPCs) have been developed using GalNAc as a targeting and masking moiety, attached to an endosomolytic polymer that promotes endosomal escape.

- Inhalable Formats: Pulmonary Delivery Breakthroughs

One promising approach for delivering siRNA is through inhalable siRNA formulations, which could be particularly beneficial for respiratory diseases that often occur alongside GI conditions. The formulation strategy utilizes the fact that siRNA can deliver its payload to the lungs upon inhalation and avoid exposure to the harsh environment of the GI tract. For example, siRNA encapsulated in nanoparticles can be delivered via inhalation to treat pulmonary fibrosis.

shRNA: The Viral Arms Race

- AAV Serotype Barcoding: Matching Capsids to Tissues

One of the more recent improvements in shRNA delivery has been the advent of AAV serotype barcoding. Engineering the AAV capsid to target a specific tissue improves the targeting of the shRNA. This targeting mechanism allows for increased specificity of shRNA delivery to the GI tract, which is the goal of the experiment. For example, AAV9 has shown potential for delivering shRNA to the central nervous system, while other serotypes can be engineered to target the GI tract.

- Lentiviral Innovations: Safety-Modified Backbones

Lentiviral vectors are another popular shRNA delivery system that has seen improvements in safety and immunogenicity. One innovation in this area is safety-modified backbones, such as SIN vectors, which are designed to prevent insertional mutagenesis. These vectors are designed so that their promoters are inactivated following integration to prevent undesired shRNA expression and to limit insertional mutagenesis.

- Non-Viral Alternatives: Transposon-Based Delivery

In addition to viral vectors, non-viral delivery methods have also seen improvements in shRNA delivery. Transposon based delivery is another promising non-viral shRNA delivery method. Examples include the transposon based system Sleeping Beauty (SB) system, which delivers shRNA constructs into the host genome and drives stable expression of the RNAi construct. Transposons can be engineered to target specific tissues and to enhance the safety of shRNA delivery.

Applications of siRNA and shRNA in Gastrointestinal Diseases

- siRNA in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Lipoplex-siRNA-2 is a liposomal enema containing chemically modified siRNA against TNF-α. Chemically modifying siRNA can increase silencing ability, enhance resistance to degradation or both. For example, propanediol and double methylation of siRNA at 3'- and 5'-end showed increased silencing ability and stability. Then the siRNA was formulated into a liposomal enema and administrated into colitic mice. Significant decreases in colonic mRNA expression (~40%) as well as mortality, DAI, MPO activity and histological scores were observed. Moreover, gene analysis of 25,000 genes showed that 4000 genes were significantly altered after colitis induction. Among the 4000 genes, expression of 60 were significantly altered during Lipoplex-siRNA-2 treatment showing the involvement of TNF-α in a wide range of proinflammatory processes. Similar effects on TNF-α inhibition and histology have been reported in another study that investigated an enema containing liposomal siRNA against TNF-α (Lipoplex-siRNA-1). The authors developed ginger-derived lipid nanoparticles (GDLNs) complexed with CD98 siRNA for the treatment of a DSS-induced murine colitis model. GDLNs complexed with CD98 siRNA showed effective gene silencing in vitro (Colon-26 cells (inflamed epithelium cells) and RAW 264.7 cells (macrophage cells)) and in vivo (the ileum and colon). Moreover, oral administration of GDLNs was shown to have better therapeutic efficacy than systemic administration of naked CD98 siRNA.

- siRNA in Gastric Cancer

siRNA-mediated selective KRT17 knockdown could significantly inhibit cell proliferation, inhibit the cell migration and invasion of gastric adenocarcinoma cells in vitro and reduce tumor growth in vivo. Interestingly, in the in vivo experiments, KRT17 expression was maintained at a low level in xenografts during 9 weeks post injection of KRT17 siRNA component. The long-acting effect comes from the method of pretreating cells with siRNA in vitro and injecting them after 48 h, when the cell proliferation rate was already diminished. Therefore, gene silencing was less affected by siRNA dilution from cell division. The SGC7901 human gastric cancer cells were transfected with VEGF siRNA to suppress VEGF expression, Bcl-2 expression and promote p21 expression. The nude mouse model was established for subcutaneous xenografts. The size and weight of the tumors were significantly smaller in the VEGF siRNA transfected group than those in the control group at 24 days after the injection. The expression of VEGF, SIRT1, survivin and Bcl-2 were decreased and p53 and p21 expression was increased in the tumor tissues of the VEGF siRNA transfected group compared to the control group. VEGF siRNA induced apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting SIRT1 expression and increasing the expression of p53 transcription, and consequently inducing p21 expression. The expression of Bcl-2 and survivin was also suppressed.

- shRNA in Gastrointestinal diseases

Oral administration of SNX10-shRNA plasmids (SRP) and PLGA nanoparticles (NPs) could effectively inhibit the inflammatory response and tissue damage of acute and chronic IBD in mice. In intestinal epithelial cells, SRP-NPs could inhibit the phosphorylation of p38, down-regulate the expression of TLR2 and TLR4, and affect downstream signaling pathways. This might be the mechanism by which SRP-NPs alleviate excessive inflammation. In vitro, the human colorectal cancer cell line SW480 with downregulation of GHSR1a by shRNA showed significant inhibition of cell viability compared with blank control (BC) or scrambled control (SC) regardless of the application of exogenous ghrelin. Moreover, GHSR1a silencing by target specific shRNA was shown capable of increasing PTEN, inhibiting AKT phosphorylation and promoting the release of p53 in SW480 cells. In addition, the effects of GHSR1a knockdown were further investigated in vivo using colorectal tumor xenograft mouse model. The tumor weights were decreased markedly in GHSR1α knockdown SW480 mouse xenograft tumors compared with blank control or negative control tumors.

Future Directions

siRNA has been demonstrated to block particular pro-inflammatory pathways implicated in gastrointestinal diseases, such as IBD and celiac disease. For instance, siRNA against TNF-α showed strong anti-inflammatory activity in mice models of colitis. siRNA against transglutaminase 2 (TG2) and the cytokine IL-15 also showed activity in reducing the symptoms of celiac disease. These studies demonstrate the potential for siRNA to inhibit the inflammatory mediators associated with GI disease and may be an alternative to conventional treatments. To be effective, stable and appropriate delivery systems need to be developed for siRNA in the gut. For instance, gelatin nanoparticles have been shown to protect siRNA from degradation and aid in cellular uptake of siRNA in the gut. For instance, gelatin nanoparticles encapsulating siRNA against TG2 and IL-15 were shown to provide sustained silencing in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, rectal delivery systems such as ultrasound-assisted siRNA delivery were shown to improve silencing efficiency. These delivery methods are necessary to overcome the challenges of the gastrointestinal tract. shRNA has also been investigated for targeting oncogenic pathways in gastrointestinal cancers. For example, shRNA against the gene encoding phospholamban (PLB) reduced tumor growth and improved survival in a mouse model of gastric cancer.

References

- Dvorská, Dana, et al. "Breast cancer and the other non-coding RNAs." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22.6 (2021): 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22063280.

- Shinn, Jongyoon, et al. "Oral nanomedicines for siRNA delivery to treat inflammatory bowel disease." Pharmaceutics 14.9 (2022): 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14091969.

- Gareb, Bahez, et al. "local tumor necrosis factor-α inhibition in inflammatory bowel disease." Pharmaceutics 12.6 (2020): 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12060539.

- Liu, An, et al. "Lentivirus-mediated shRNA interference of ghrelin receptor blocks proliferation in the colorectal cancer cells." Cancer Medicine 5.9 (2016): 2417-2426. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.723.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.