miRNA in Cancer Therapy-From Molecular Guardians to Therapeutic Game-Changers

Introduction of miRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the most abundant class of endogenous non-coding small RNAs, regulating the expression of about one-third of human genes. MicroRNAs are single-stranded RNA molecules between 19 and 25 nucleotides in length that can function as mRNA binding agents, inhibiting the expression of target genes through partially complementary binding to 3' UTR sites in target mRNA molecules. Most of the binding interactions result in a decrease in translational capacity, as well as endonucleolytic cleavage of the mRNA. It has been proposed more recently that some miRNAs function as activators. As miRNAs have been implicated in a number of biological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, it is not unexpected that miRNAs are associated with cancer and potential for cancer therapeutics. Because miRNAs are small, they are not easily degraded and can be obtained from any cell or tissue type. Indeed, miRNAs are shown to be present in FFPE tissue for up to 10 years post collection. This allows for retrospective analysis of archived patient samples. Furthermore, serum and plasma miRNAs are easily measurable in whole blood. Multiple studies have demonstrated cancer-specific miRNAs in the circulation of cancer patients.

miRNA Dysregulation in Cancer

- Oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs) and Tumor Suppressor miRNAs

Some miRNAs have been identified as oncomiRs. For example, miR-21 is overexpressed in many cancers, including breast, lung, and prostate cancers. It targets the tumor suppressor genes PTEN and PDCD4 and induces cell proliferation and cell cycle arrest and cell death. Another cancer-related miRNA is miR-155. It is overexpressed in a wide variety of cancers and targets genes involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis. However, there are also tumor suppressor miRNAs that target oncogenic genes. For example, let-7 targets the oncogenes K-Ras and c-Myc, and its downregulation is correlated with poor prognosis in several types of cancer. Another example is miR-34a, which targets cell cycle regulator and cell survival genes such as SIRT1 and BCL2.

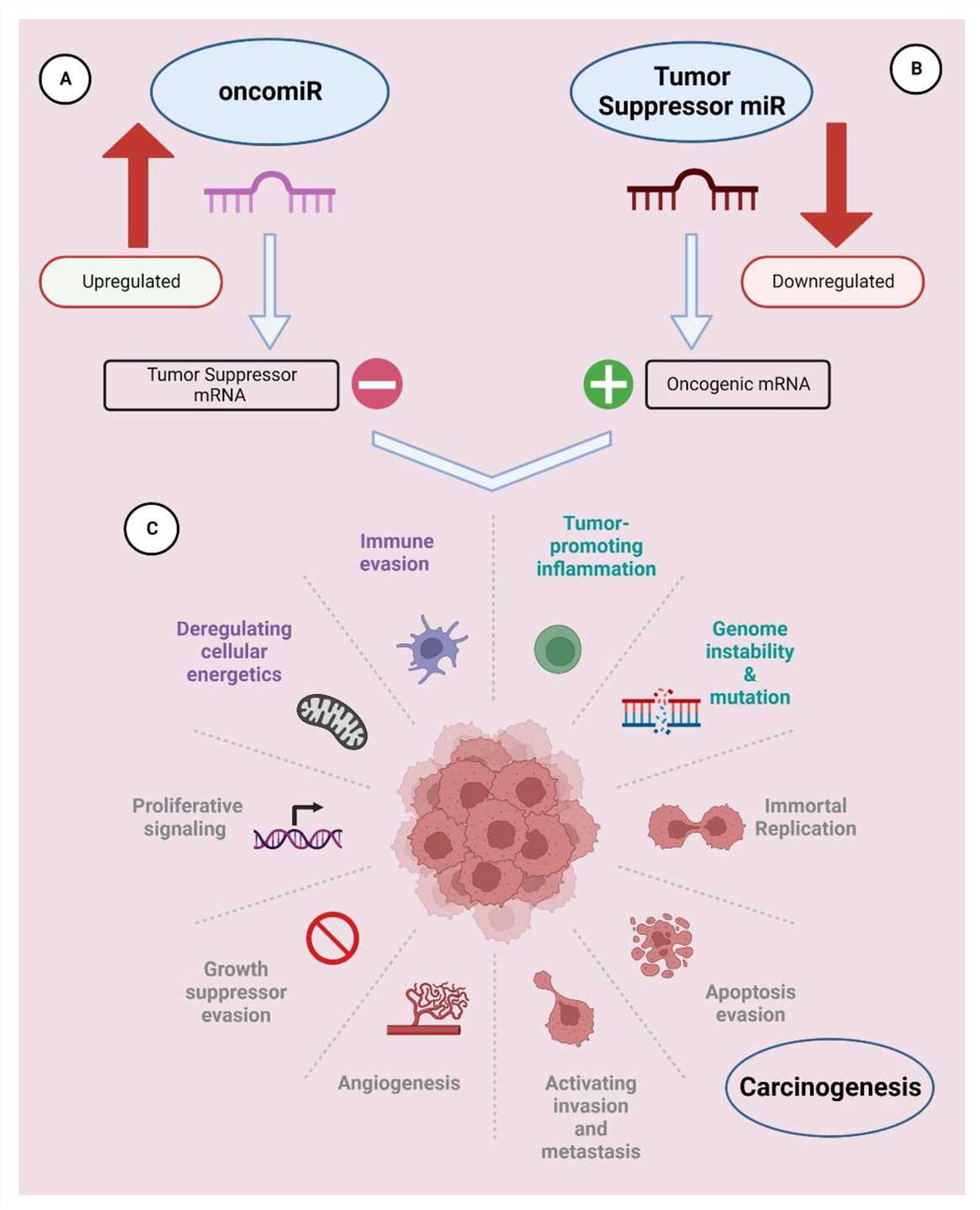

Fig.1 miRNAs can be classified as oncomiRs and tumor suppressors1,6.

Fig.1 miRNAs can be classified as oncomiRs and tumor suppressors1,6.

- miRNA Signatures in Different Cancer Types

Several miRNAs are oncogenes (oncomiRs). Both up-regulation and down-regulation of miRNAs in uterine endometrioid cancer compared to benign specimens. Several miRNAs of interest that were different between benign endometrium and endometrioid cancers. Up-regulation of the mir-200 family has been recently demonstrated in well-differentiated cancers, and is observed in our endometrioid samples. Expression of miR-183 is inversely correlated with the metastatic potential of lung cancer cells. MiR-200 has been recently reported to be up-regulated in well-differentiated cancers and is observed in our endometrioid samples. Mir-183 is inversely correlated with the metastatic potential of lung cancer cells. MiR-183 expression is decreased by 2- to 3-fold in highly metastatic lung cancer cells versus non-metastatic cells from the same cell lines. As it is not unexpected that mir-183 is also up-regulated in endometrioid cancer which rarely metastasizes, MiR -205 and MiR -182 are also up-regulated in endometrioid carcinomas.

- miRNA as Biomarkers

A robust signature has been defined in clear cell renal cell cancer (ccRCC) samples using expression profiles for 5 miRNAs which are highly overexpressed in tumors and 6 miRNAs which are highly downregulated. A unique miRNA combination (high miR-155 and low miR-141) can correctly classify the paired malignant and non-malignant tissues in 97% of cases. The interactions between the predicted miRNA and mRNAs obtained from PicTar, TargetScan and miRBase can be retrieved by integrating the molecular-bioinformatics approach. Calculating the difference in the ΔCt value between miR-503 and miR-511 allows the distinguishing of adrenocortical carcinomas from benign adenomas with high sensitivity and specificity. These miRNAs may prove useful in diagnosis of adrenocortical malignancy. TP53 (tumor protein 53) mutation and 17p deletion are responsible for chemoresistance in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). miR-34a has a low expression which inactivates p53 and leads to chemoresistance, DNA damage response insensitivity and defective apoptosis in the presence of TP53 mutation or 17p deletion. miR-34a is also linked to chemoresistance and can be a marker for poor prognosis in CLL.

Designing miRNA-Based Therapies

Strategies for miRNA Replacement Therapy

miRNA replacement therapy is the delivery of chemically synthesized miRNAs or miRNA mimics into cells in order to restore/enhance the endogenous miRNAs. Synthetic miRNAs are chemically identical to the endogenous miRNAs in sequence and function, and have 17–26 nts. Synthetic miRNAs can be delivered into the cytoplasm of cancer cells by different transporters such as reagents or electroporation and emulating the endogenous miRNA. Endogenous templates are designed for these synthetic miRNAs and are combined in the cytoplasm with RISC and do not enter the cell nucleus. For the first time, miRNA let-7, which is downregulated in many types of tumors, was examined in this way. Several in vitro studies have demonstrated the therapeutic value of overexpression of let-7 with miRNA mimics. For example, the inhibition of let-7a in laryngeal tumor cells and hepatic cancer cells was associated with cell growth promotion and administration of let-7 mimics inhibited tumor cell growth. In addition, the transfection of let-7 mimics in colon cancer cells induced increased apoptosis and reduced tumor cell proliferation.

Strategies for miRNA Inhibition

- Antagomirs (Anti-miRs)

Antagomirs are chemically modified antisense oligonucleotides which specifically target oncogenic miRNAs and inactivate them. They reduce expression of the overexpressed miRNAs in cancer cells by blocking the oncogenic miRNAs. Antagomirs against miR-21 inhibited tumor growth and induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. miRNA sponges can knockdown oncogenic miRNAs. They are synthetic RNAs containing multiple binding sites for a specific miRNA and thus bind and neutralize the miRNA so it can't bind to its target mRNA. miRNA sponges knocked down miR-155 in leukemia cells and downregulated oncogenic pathways and improved treatment outcomes.

- Challenges in miRNA Therapy Design

The major challenges in miRNA therapy include off-target effects which occur when miRNA binds to other mRNAs with partial sequence complementarity and regulate them. They may be both harmful and beneficial. For example, a miRNA that binds to many mRNAs coding for cancer-related proteins and antagonizes these mRNAs can be used to combat cancer. Off-target effects of miRNA mimics and inhibitors have been countered by designing more specific and selective miRNA mimics and inhibitors and computational methods to predict and avoid off-target effects. Major limitations of miRNA mimics and inhibitors are their instability and low delivery to target cells. They are degraded in the blood by nucleases and carry a negative charge which prevent cellular uptake. Many delivery vehicles have been developed for miRNA mimics and inhibitors, including lipid nanoparticles, exosomes, and viral vectors. Various chemical modifications to miRNA mimics and inhibitors have been studied including 2′-O-methoxyethyl (MOE) and locked nucleic acid (LNA).

Generation and Delivery of miRNA Therapeutics

- Synthetic miRNAs

Synthetic miRNAs are made in a chemical synthesizer which uses phosphoramidites to create oligonucleotides. miRNAs can be made to a high degree of purity, and services for commercially produced miRNAs are available. The purity of the miRNAs is low and the price is expensive for miRNAs greater than 70–80 nucleotides. Therefore, miRNAs greater than 70–80 nucleotides are not commonly produced. miRNAs can also be produced from short oligonucleotides by using enzymes to ligate the oligonucleotides into longer sequences. In practice, it has been challenging to produce a mixture of miRNAs at a level comparable to in vivo miRNAs. However, chemically modified miRNAs are possible to synthesize which are more stable and less likely to stimulate the immune system. Modifications include 2′-O-methyl or LNA nucleosides.

- Delivery Systems

Lipid nanoparticles encapsulating miRNAs have been reported to be effective for miRNA delivery. Neutral liposomes made of neutral lipids and helper lipids (e.g. DOPE, PEG, PCs, cholesterol) have been reported to avoid RES uptake and prolong the circulation time. Neutral liposome delivery of miR-34a and let-7b mimics reduced tumor burden in a mouse model of non-small cell lung cancer. Ionizable liposomes (cationic at low pH and neutral/anionic at higher pH) have increased cell selectivity and promising preclinical results. Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles which are naturally non-immunogenic and can load miRNAs and target specific cell types. Exosome-based delivery vehicles can be engineered to target tissue and improve the efficacy of miRNA-based therapeutics. Polymer-based vectors can be synthetic biodegradable polymers and natural polymers (chitosan) which can be chemically modified. Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles delivered miR-34a mimics which reduced tumor size and improved survival in a multiple myeloma xenograft. Polymer toxicity and degradation still needs to be improved to make them clinically relevant.

- In Vivo Delivery Challenges and Solutions

One of the major challenges for miRNA therapeutics is the immune response to the delivery vehicles. An example of this is the ionizable liposome-miR-34 complex (MRX34) that was terminated prematurely from phase I clinical trial due to severe immune-related adverse events. Modification of the delivery vehicle or use of less immunogenic materials is being explored. Tissue targeting is important to maximize the therapeutic effect and reduce the side effects. Tissue targeting could be achieved by the use of tissue specific ligands or changing the surface property of the nanoparticle so that the nanoparticle has high uptake rate of the target cells. For example, the PLGA nanoparticles were conjugated with positive charged PEI and anionic hyaluronic acid, so they could deliver miR-145 to colon cancer cells in vivo.

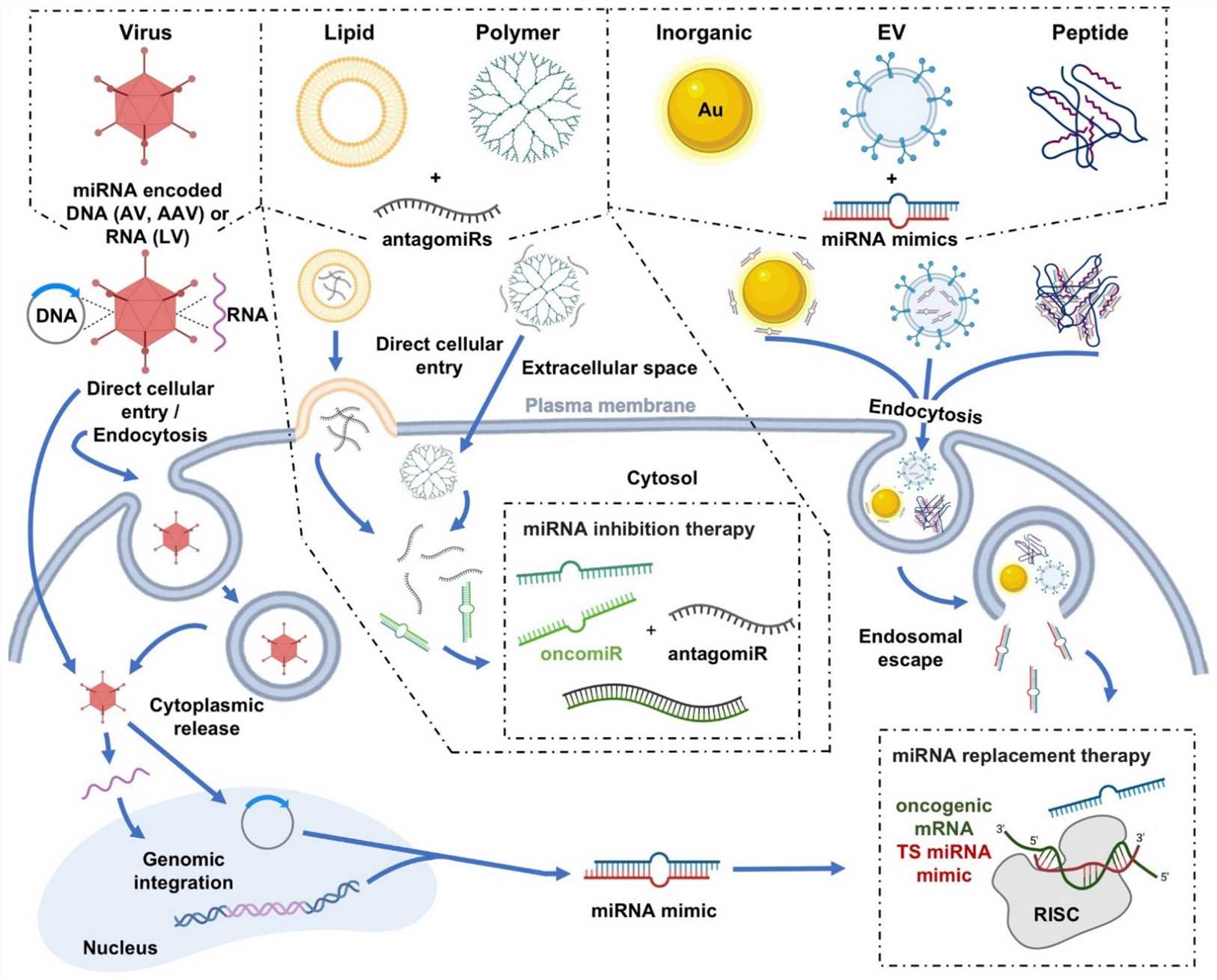

Fig.2 Graphical depictions highlighting the varied miRNA delivery platforms developed for cancer therapeutics, as well as their mechanisms of cellular internalization2,6.

Fig.2 Graphical depictions highlighting the varied miRNA delivery platforms developed for cancer therapeutics, as well as their mechanisms of cellular internalization2,6.

miRNA in Cancer Therapy: Clinical Applications

- Targeting Oncogenic miRNAs

Certain miRNAs that play a role in oncogenesis have garnered much interest as inhibitors of these molecules have shown preclinical and clinical promise. The liposomal miR-34 mimic MRX34 is the first candidate miRNA-based drug to enter a phase I clinical trial for metastatic cancer with liver involvement and unresectable primary liver cancer. A modified version of anti-miR-122, called RG-101, was tested in a phase II clinical trial for HCV in liver transplant patients. Other miRNA inhibitors are being tested in combination with cancer therapeutics in pre-clinical studies. For example, delivery of ASOs that target miR-21 and miR-221 sensitizes PDAC cells to gemcitabine and results in increased cancer cell death.

- Reconstituting Tumor Suppressor miRNAs

A number of preclinical studies have shown that tumor suppressor miRNAs can be restored. The restoration of let-7 by nasal delivery was shown to decrease tumor formation in an orthotopic mouse model of lung cancer. Restoration of miR-34 in non-small-cell lung cancer cells reduced tumor size significantly. Several clinical trials are ongoing for miRNA mimics. TargomiR, a miR-16 mimic administered in a suspension of bacterial minicells, was tolerated well and had no serious adverse events in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma and non-small-cell lung cancer.

- miRNA-Based Vaccines

MiRNA-based vaccines are a new type of cancer immunotherapy that is currently being studied in the laboratory. It is a new field that could potentially lead to personalized cancer treatment. There have been a few preclinical trials of miRNA-based cancer immunotherapy, which have shown some positive results. MiRNA-based vaccines could allow the immune system to become better at recognizing and killing cancer cells through altering miRNA expression in immune cells.

Clinical Status and Future Directions

Several clinical trials involving miRNA are being conducted. For example, in the phase I clinical trial of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34 mimic, it was found that the miRNA replacement therapy can be effective in cancer treatment. Meanwhile, the phase I clinical trial of the miR-16 mimic TargomiR for thoracic cancer patients was successful. Nonetheless, several obstacles need to be overcome before miRNAs can be applied clinically. Such as off-target effects and immunogenicity must be decreased. In addition, the delivery of miRNAs is the main challenge in the use of miRNAs in clinical settings. The future of miRNA therapy will be in the realm of personalized medicine. Treatment can be personalized by targeting the unique miRNA signature of the patient's cancer subtype. MiRNA based treatments can be administered in combination with other precision medicine treatments like targeted therapies and immunotherapies, and thus potentially enhance treatment efficacy. Complementary treatments synergistically fight cancer by hitting it from different angles. Lipid nanoparticles and exosomes are also being developed to address the issues surrounding miRNA therapies. These methods aim to increase stability, specificity, and deliverability of miRNA-based treatments.

References

- Chakrabortty, Atonu, et al. "miRNAs: potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer." Genes 14.7 (2023): 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14071375.

- Holjencin, Charles, and Andrew Jakymiw. "MicroRNAs and their big therapeutic impacts: delivery strategies for cancer intervention." Cells 11.15 (2022): 2332. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11152332.

- Smolarz, Beata, et al. "miRNAs in cancer (review of literature)." International journal of molecular sciences 23.5 (2022): 2805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23052805.

- Kim, Taewan, and Carlo M. Croce. "MicroRNA: trends in clinical trials of cancer diagnosis and therapy strategies." Experimental & molecular medicine 55.7 (2023): 1314-1321. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01050-9.

- Pagoni, Maria, et al. "miRNA-based technologies in cancer therapy." Journal of personalized medicine 13.11 (2023): 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13111586.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.