miRNA-The Subtle Orchestrators of Gene Regulation

What is miRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs, generally 18–25 nucleotides in length. They regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. The vast majority of miRNAs are transcribed from DNA to become mature miRNAs that often bind to mRNA and repress translation or target mRNA for degradation by binding to the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR). They can also target the 5' UTR, the coding region, or the gene promoter. They can also activate translation and transcription. miRNAs are involved in many biological processes, such as development, differentiation, and stress response. miRNAs are involved in many diseases and can be therapeutically targeted. In cancer, miRNAs act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on the target gene. In the nervous system, miRNAs regulate synaptic plasticity and neurodegeneration.

Biogenesis and Mechanism of miRNAs

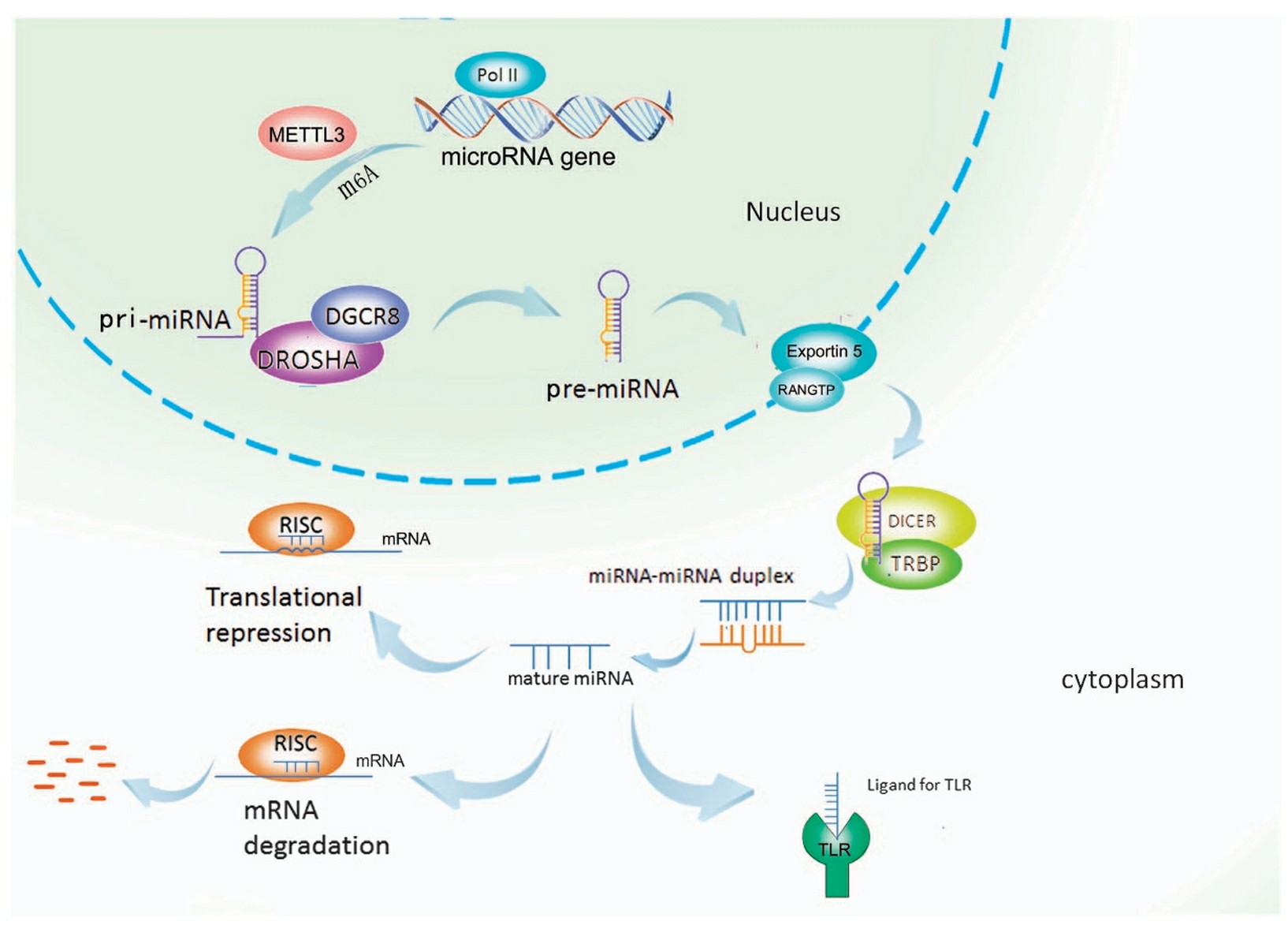

miRNA biogenesis in vertebrates has five steps. The first step is to synthesize miRNA in the form of a long primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) and probably by RNA polymerases type II (Pol-II). Pri-miRNA is transcribed from the genome. In the second step, the long pri-miRNA is cleaved into approximately 60–70 nt precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) by Drosha-like RNase III endonucleases and/or spliceosomal components. Pre-miRNA has substantial secondary structure, including regions of imperfectly paired dsRNA. The pre-miRNA is cleaved to one or more miRNAs sequentially. This step is dependent on the origin of the pri-miRNA, i.e., from an exon or an intron respectively. The third step is to export pre-miRNA from the nucleus by Ran-GTP and a receptor, Exportin-5. Pre-miRNA molecules are further processed by Dicer-like endonucleases into mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm. Loading of the mature miRNA into a ribonuclear particle (RNP) to form the RNA-induced gene silencing complex (RISC), the enzyme complex that mediates the RNAi related gene silencing, is the last step in the process. The miRNA inhibits mRNA translation through partial complementarity to the target mRNA, especially in the 3' UTR of the mRNA.

Fig. 1 microRNA biogenesis1,5.

Fig. 1 microRNA biogenesis1,5.

Design of miRNA-Based Therapies

- Sequence design

Just like designing a siRNA, the first step is to identify a unique sequence within the 3'UTR of the gene of interest (target mRNA). However, unlike the full complementarity between a siRNA and the target sequence within the gene, the miRNA mimic only partially base pairs with the target sequence in the 3'UTR. A minimal length of sequence for the miRNA action is at least 8 nts, and an optimal length is >14 nts. To design miRNA-based therapeutics, target sequences need to be selected with consideration for high binding and inhibition of miRNAs. The target sequence should be complementary to the mature miRNA and should focus on the seed region since this is the region important for the miRNA-mRNA interaction. For anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs), the seed region at the 5' end of the mature miRNA should be matched for higher binding affinity and specificity. It should also be checked against the human genome using tools like BLAST to avoid off-target effects.

- Chemical modification

Chemical modification is required to improve nuclease stability of miRNA. A number of 2'-sugar modifications have been demonstrated to confer nuclease stability, including 2'-O-Me, 2'-F, 2'-deoxy, 2'-MOE and LNA, which have been tested and tolerated to various degrees on either the sense or antisense strands. Introducing phosphorothioate internucleotidic linkages, which promote plasma protein binding and delay renal clearance of single-stranded oligonucleotides, in addition to conferring nuclease stability, is tolerated by miRNAs in cell culture, and a positive effect on in vivodelivery has been reported.

Applications of miRNA in Disease Therapy

- miRNAs in Chemotherapy

Cisplatin (CP), a nonspecific cytotoxic drug that can crosslink with DNA, causes the damage of DNA function and arrest cell mitosis, is often used as a chemotherapeutic agent. Most patients become resistant to chemotherapeutics and chemoresistance is one of the main reasons for cancer chemotherapy failure. MiR-149 resensitizes drug-resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells to CP by targeting ERCC1, a gene that promotes abnormal DNA damage repair. MiR-488 induces CP resistance in NSCLC cells by upregulating XPC expression through the regulation of the elF3a/NER pathway. MiRNAs can also induce cellular drug resistance by regulating the expression of key genes or signaling pathways in autophagy. MiR-23a reverses drug resistance in NSCLC by inhibiting autophagy via the AKT signaling pathway to induce apoptosis. MiR-124 and miR-142 promote the sensitivity of NSCLC cells to CP by targeting SIRT1 to inhibit autophagy. MiR-1269b increases the breakage of the autophagosome by regulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to reverse CP resistance. miR-744-5p/miR-615-3p inhibit GPX4-mediated ferroptosis and reverse CP resistance in NSCLC. Other miRNAs including miR-4333, miR-522, and miR-362-3 can regulate ferroptosis to impact chemoresistance.

- miRNAs in Radiotherapy

MiR-296 expression was downregulated, whereas the expression of lncRNA AGAP2 antisense RNA (AGAP2-AS1) was upregulated in lung cancer cells and tissues. The M2 macrophage-derived exosome AGAP2-AS1 increased the radioresistance of lung cancer by downregulating miR-296 and upregulating NOTCH2. MiR-219a-5p could promote the radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells via targeting CD164. Recently, miR-20b-5p was also found to increase the radiosensitivity of lung cancer cells via targeting PD-1. In the transplanted tumor-bearing nude mice, either pembrolizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti-PD1 antibody, or miR-20b-5p overexpression promoted the radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells. A clinical study suggested that miRNAs may be used as biomarkers to select patients who can benefit from high-dose radiotherapy (RT). With a better understanding of miRNAs, the miRNA-based therapy combined with RT could be an attractive personalized treatment approach. In the next decade, more and more miRNAs showed anti-NSCLC effects in animal studies, and more delivery systems have been introduced. Liposomes-mediated miR-29b and miR-200c suppressed the proliferation and increased the radiosensitivity of NSCLCs.

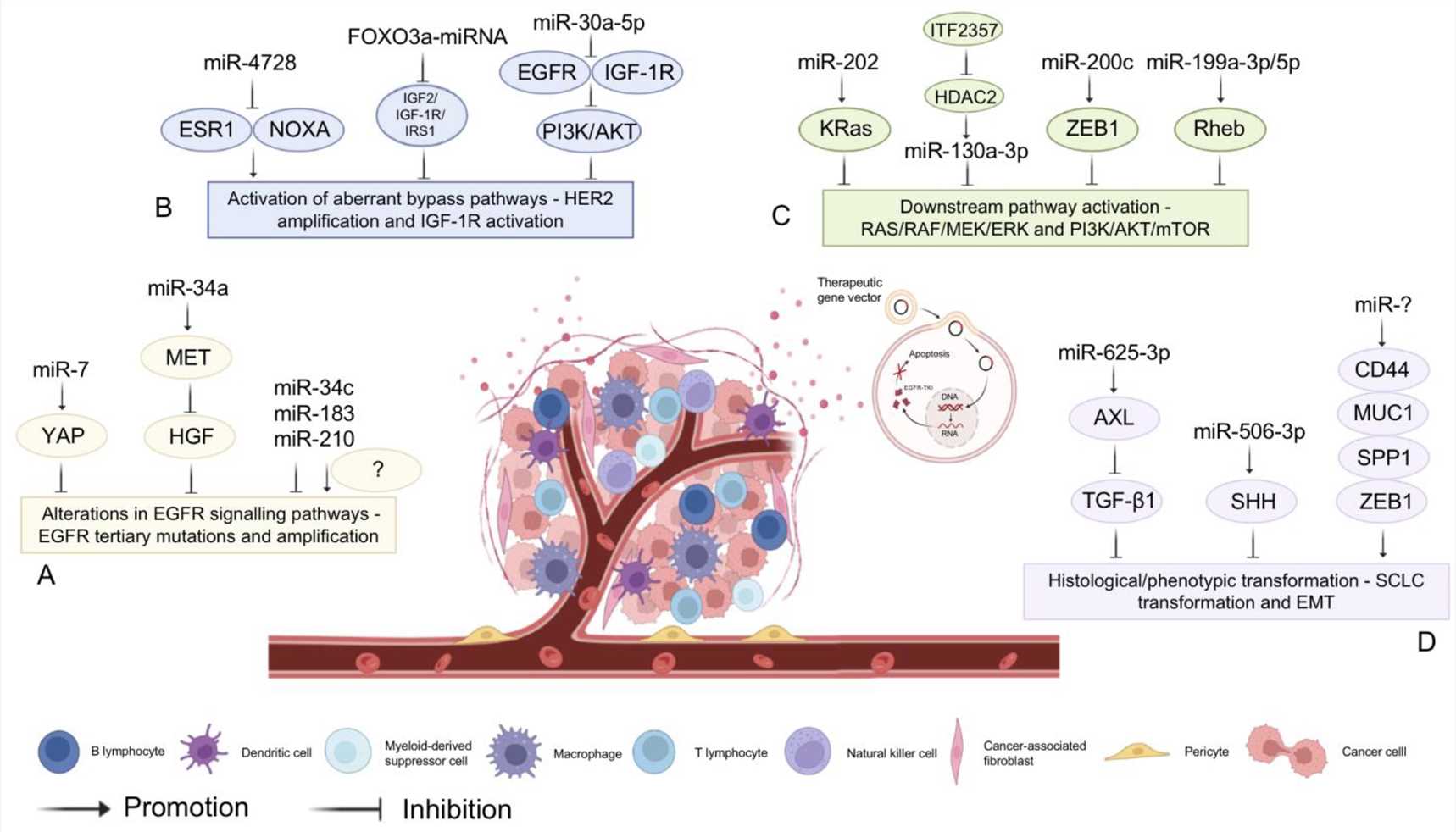

- miRNA-assisted Targeted Therapy

Many miRNAs are reported to be associated with the regulation of EGFR-TKI, suggesting that miRNAs could be a novel class of therapeutic agents and biomarkers for anti-EGFR therapy, and have a positive effect in reversing drug resistance and increasing sensitivity. Moreover, researchers identified the miR-608 and miR-4513 single nucleotide polymorphisms as independent biomarkers for predicting the survival of lung adenocarcinoma patients after EGFR-TKI treatment by screening the database of 1000 genomic projects in miRbase and obtaining data from 319 stage IIIB/IV patients who were treated with EGFR-TKI. Nevertheless, the development of resistance, either de novo or acquired, may impede the long-term use (less than one year) of EGFR-TKIs. The expression levels of miRNAs in response to EGFR-TKI treatment were found to be different between drug-resistant and sensitive tumor cells and were regulated differentially; thus, miRNA-based therapy may be a possible approach to reverse drug resistance and present a targeted therapy for the adjuvant treatment of cancer. For example, the expression of miR-125a-5p, which exerts its antitumor effects by targeting EGFR, was downregulated in human tumor cells.

Fig. 1 MiRNA-assisted targeted therapy2,5.

Fig. 1 MiRNA-assisted targeted therapy2,5.

- miRNA-Assisted Immunotherapy

The first human miRNA to be identified, Let-7 was found to block tumor growth in a mouse model in 2008. The PD-L1 and PD-1 expression of tumor microenvironment was post-transcriptionally inhibited by treatment with let-7b. The expression of PD-1 on CD8+ T cells was inhibited by let-7b, while PD-L1 expression in lung cancer cells was inhibited, and the function of antitumor CD8+ T cells was increased. The expression of miR-4458 increased and suppressed tumor growth. The percentage of PD-1+ T cells and PD-L1 and IL-10 expression were downregulated, and the percentage of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ and IL-2 expression were upregulated. miR-488 and miR-181a-5p targeted the JAK/STAT pathway and the role of immunotherapy needs to be studied.

Delivery Vehicles for miRNA-Based Therapy

The vectors used for gene delivery for therapeutic miRNA are divided into two types: viral carriers (which contain the genetic material) and non-viral carriers (cationic molecular carriers, particularly lipids and polymers). These carriers interact electrostatically with nucleic acids and facilitate gene delivery to the cell.

- Viral Vectors

Because of their transduction efficiency and their sustained expression in many cell types, synthetic viral vectors are becoming important for gene therapy. Viral vectors may deliver miRNAs at various steps of biosynthesis (pri-miRNAs and pre-miRNAs). Promoted by a viral promotor, the pri-miRNAs and pre-miRNAs molecules (cloned into the plasmids) may be transcribed and processed to mature miRNAs and targeted the mRNAs. The most commonly used viruses for therapeutic gene delivery and which have been applied with miRNAs in several cancer models are adenoviruses (AdVs), lentiviruses (LVs), and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). Limitations concerning adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses include immunogenicity and the short miRNA expression period while lentiviruses include a safety risk of the genomic integration procedure. Oncolytic AdVs (OAdVs) have been used to deliver miRNA mimics and anti-miRNAs. For example, the growth of TNBC xenografts was inhibited using OAdV delivery of anti-miRNAs in the form of lncRNAs that repressed onco-miRNAs, and researchers showed therapeutic effects of the upregulation of miRNA-7 and the downregulation of miRNA-21 using AAV delivery of anti-miRNA-21 and miRNA-7 in mice bearing malignant brain tumors.

- Non-Viral miRNA Delivery

Virus-mediated delivery strategies of miRNAs have been shown to be highly effective but are still limited in their clinical applications due to a number of biosafety concerns, such as immunogenicity. Non-viral delivery systems are useful for the transport of endogenous miRNAs or miRNA-expressing vectors. Non-viral carriers can resist nuclease degradation through the use of organic, inorganic, or polymer carriers.

- Lipid-Based Delivery Systems

Non-viral vectors that have been most commonly used are those that are based on organic carriers, for example, the liposomes encapsulating nucleic acids. Effective therapy was demonstrated in preclinical and clinical cancer studies by lipid-based drug delivery. Cationic, anionic, and neutral liposomes are being used because of their higher affinity to the cellular membrane due to their being amphipathic. Liposomes are the central building block for all LNPs that undergo further chemical modifications such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) to facilitate tumor targeting and stability. The optimization of the properties of lipid-based nanoparticles has created ionizable liposomes which are able to alter their charge state in response to changes in pH which are now considered to be clinically translatable. Although a liposome formulation (MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic) was tested in liver cancer, the side effects were pronounced and the trial was terminated after four deaths. Furthermore, a study showed that an miR-199b-5p mimic can be delivered to cancer stem cell markers in multiple cancer cell lines via ionizable liposomes.

- Polymeric Nanoparticles

Among the delivery systems for miRNA-based therapeutics in cancer, polymer-based systems have proven successful as efficient delivery vectors for nucleic acids. Polymer-based systems have the advantages of high stability, flexibility, and ease of functional group substitutions. These can be categorized as natural and synthetic polymer-based systems. The natural polymers being studied for gene therapy are chitosan, collagen, gelatin, and their derivatives. Chitosan and other natural polymers are biodegradable, pH-sensitive, muco adhesive, and possess good drug release properties, making them potential candidates for drug carriers. Other natural polymers such as cell-penetrating peptides (CPP) can penetrate the cellular membrane and deliver a wide range of active conjugates. CPP-conjugated nanoparticles have been shown to be more stable, exhibit increased cellular uptake, and have reduced cytotoxicity but may lead to endosomal entrapment and particle aggregation.

- Exosome-Mediated Delivery of miRNAs

Exosomes, cell-derived nanovesicles with a diameter of 40–100 nm, which are involved in cell-to-cell communication in health and disease.. As they come from the plasma membrane, exosomes are safe, biocompatible, and do not trigger immune response in vivo. They can cross the blood–brain barrier. The major challenges with the exosome application are the limited production of large amounts of highly purified exosomes and rapid clearance of exosomes from the blood circulation and the tendency of accumulation in vital organs. These problems should be solved before its application in clinic. Some research has been carried out on the delivery of exosome nanovesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The MSCs nanovesicles carrying synthetic miRNA-143 can suppress the migration of osteosarcoma cells, but compared with lipofection, the efficiency was lower. For the diagnosis and miRNA therapy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), an effective experiment has been performed. The exosomal hsa_circ_0012634 inhibits the PDAC progression through the miR-147b/HIPK2 axis and it may serve as a potential biomarker.

References

- Peng, Yong, and Carlo M. Croce. "The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer." Signal transduction and targeted therapy 1.1 (2016): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4.

- Yang, Han, et al. "MiRNA-based therapies for lung cancer: opportunities and challenges?." Biomolecules 13.6 (2023): 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13060877.

- Pagoni, Maria, et al. "miRNA-based technologies in cancer therapy." Journal of personalized medicine 13.11 (2023): 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13111586.

- Ho, Phuong TB, Ian M. Clark, and Linh TT Le. "MicroRNA-based diagnosis and therapy." International journal of molecular sciences 23.13 (2022): 7167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23137167.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.