miRNA in Infectious Diseases-Fine-Tuning the Immune Response

Introduction to miRNA in Infectious Diseases

The discovery of the first miRNA (lin-4) in 1993 within Caenorhabditis elegans was a major impact on molecular biology. They found out that lin-4 is one of the genes for the temporal development of C. elegans larvae. MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs with an average size of 22 nucleotides. Most miRNAs are derived from the DNA sequences and are processed into pri-miRNAs and pre-miRNAs and then mature miRNAs. Usually, miRNAs bind to the 3' UTR of the target mRNAs and repress the expression of genes. However, miRNAs can also bind to the 5' UTR, coding sequence, and gene promoter region and even induce the expression of genes in special cases. Some research indicates that miRNAs shuttle between different subcellular compartments to regulate the translation rate and even transcription. Infectious diseases are a widespread problem and miRNAs are emerging as potential diagnostic and therapeutic agents. They could be used to inhibit the replication of the virus or bacteria. They could be used to target the viral genome and prevent its replication or they could target the virulence factors of the bacteria and reduce the severity of the infection.

The severity of Infectious diseases

The direct impact of infectious diseases causes approximately 15 million deaths from a total estimate of 57 million annual worldwide deaths which amounts to more than 25%. streptococcal rheumatic heart disease) or as a result of complications from chronic infections such as liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma among those infected with hepatitis B or C virus. Infectious agents that cause chronic diseases represent one of the most difficult categories of newly emerging (or at least newly appreciated) infections. Associations with hepatitis B and hepatitis C and chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma, with certain genotypes of human papillomaviruses and cancer of the uterine cervix, with Epstein–Barr virus and Burkitt's lymphoma (predominantly in Africa) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (predominantly in China), with human herpesvirus 8 and Kaposi sarcoma, and with Helicobacter pylori and gastric ulcers and gastric cancer, are well known. In fact, there is some data even to suggest infectious aetiologies for such common causes of death and disability as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus53. Other links between infectious agents and idiopathic chronic diseases will undoubtedly be discovered.

Mechanisms of miRNA-Mediated Gene Regulation in Infectious Diseases

The minimal miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) contains the guide strand and AGO. miRISC target specificity is conferred by the interaction with complementary sequences on the target mRNA, termed miRNA response elements (MREs). The degree of complementarity between miRNA and MRE defines the extent of AGO2-mediated slicing of target mRNA versus miRISC mediated translation repression and target mRNA decay. In animal cells, most miRNA:MRE interactions are not fully complementary. Most MREs contain at least central mismatches to their guide miRNA. These mismatches prevent AGO2 endonuclease activity. AGO2 functions as an intermediary of RNA interference like the non-endonucleolytic AGO family members (AGO1, 3, and 4 in humans). Most functional miRNA: MRE interactions occur via the 5' seed region. Formation of a silencing miRISC complex begins with recruitment of the GW182 family of proteins by miRISC; GW182 provides the framework to recruit other effector proteins such as the poly(A)-deadenylase complexes PAN2-PAN3 and CCR4-NOT following miRNA:target mRNA interaction. Target mRNA poly(A)-deadenylation begins by PAN2/3 and ends by the CCR4-NOT complex. Binding of the tryptophan (W)-repeats of GW182 and poly(A)-binding protein C (PABPC) enhance the deadenylation. Then, decapping is facilitated by decapping protein 2 (DCP2) and associated proteins and 5'−3' degradation by exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1).

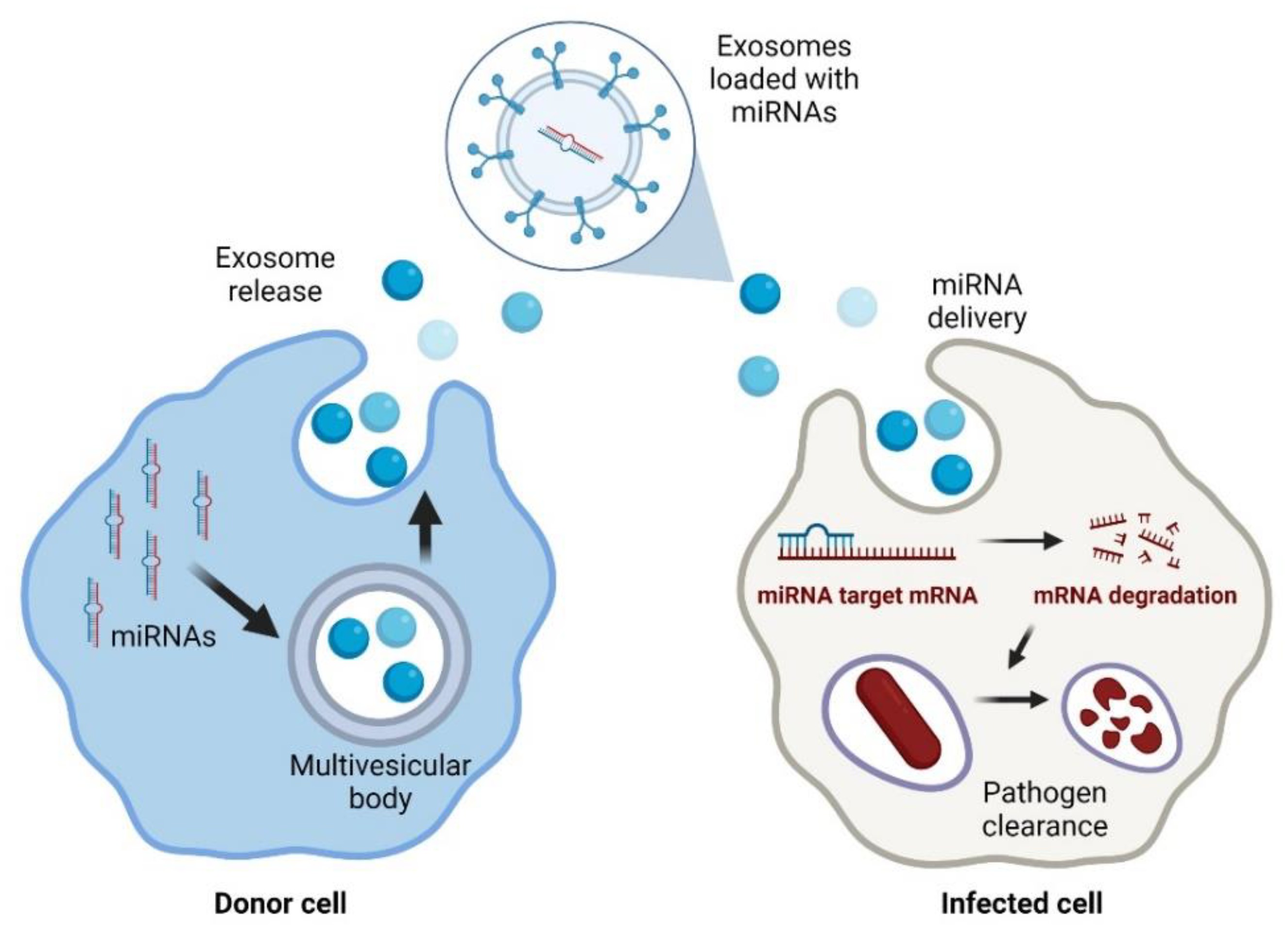

Fig. 1 Exosomal delivery of antimicrobial miRNAs to infected cells1,6.

Fig. 1 Exosomal delivery of antimicrobial miRNAs to infected cells1,6.

MiRNA Applications in Viral Infections

Viruses may adopt many strategies to ensure their success of replication in a proper host and the host miRNAs are no exception. Some DNA viruses have evolved to encode their own miRNAs to regulate both the viral and cellular protein expression to promote viral replication in the infected cells. In turn, some host miRNAs can regulate the cell gene expression to protect the cells from the virus infection by targeting the viral proteins or other cellular factors as an innate immune response against the specific viruses. As a result, the interaction between viruses and miRNAs is complicated, and the potential target genes of miRNAs are also diverse. Because of the crucial role of miRNAs in viral infections, they are also considered as the potential targets in infectious diseases. Their endogenous, small size and flexible functions render miRNAs good candidates since they may generate less immunogenic responses and less side effects compared with siRNAs.

- Cytomegalovirus

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a member of the human herpesviruses that cause acute and latent infection. As with other herpesviruses, miRNAs have been identified that play a role in the pathogenesis of the virus in various tissues. The latent infection caused by HCMV can be induced by the virus by means of an ingenious immune-evasion mechanism in which miR-UL112 down-regulates several cellular proteins, such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I associated proteins, especially the MHC class I-related chain B (MICB). miR-UL112-1 also down-regulates early viral protein expression, such as immediate early protein (IE)-72. IE72 is a protein that mediates the shift from the latent phase to the active phase of infection, since IE1 is suppressed by IE72. Thus, if the HCMV infection occurs in a state of miR-UL112 overexpression, the IE1 protein expression level is greatly reduced, and this mediates the latent phase of infection. Additionally, miR-UL112-1 has been proposed to target another viral protein, called UL114. When UL114 protein is downregulated using miR-UL112-1, the virus will undergo inhibition of DNA replication, and will subsequently enter the latent phase of infection, allowing the virus to escape from the host immune system. This strategy is being explored as a therapeutic method.

- Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

EBV is another human oncovirus. The induction of latent infection is associated with more than 95% of affected patients. Recently, it has been reported that EBV encodes more than 20 miRNAs. These miRNAs can be divided into two groups: one group is encoded from the intronic region of a gene called BART, which is highly expressed in epithelial cells, but not expressed in B cells in the latent infection phase; the other group is encoded from the untranslated region of a gene called BHRF1, a viral BCL2 homolog which inhibits apoptosis. It was reported that miRNA-BART2 targets BALF5 mRNA, a viral DNA polymerase. miRNA-BART2 can cleave BALF5 in the 3' UTR to inhibit the lytic viral infection. According to the bioinformatic prediction, EBV miRNA-BART5 may target PUMA, a modulator of apoptosis in the BCL2 protein group regulated by TP53. In some cases, PUMA can induce apoptosis through the TP53-independent pathway. So, EBV miR-BART5 targets PUMA, which results in suppression of its function in apoptosis.

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus (SARS)

The Coronaviridae family includes the single-stranded RNA virus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Several clinical trials have been performed on using traditional medicines, such as ribavirin, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory steroids and several immune stimulators which are not viral specific. SARS-CoV in bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) is one way that miRNA regulate the virus-host interaction. SARS-CoV is not capable of replicating in well differentiated cells, so SARS-CoV controls BASC cellular differentiation to be able to successfully infect the host. SARS-CoV can hijack cellular miRNAs such as miR-17, miR-574-5p and miR-214 to be used for viral replication and immune evasion. Nucleocapsid and spike glycoproteins reduce the expression of miR-223 and miR-98 respectively. The action prevents BASC cellular differentiation and the production of inflammatory chemokines, resulting in a favourable condition for virus replication. Resurrection of miR-223 and miR-98 levels may provide a novel approach for treating SARS-CoV infection.

miRNA Applications in Bacterial Infections

The first miRNA associated with a bacterial infection was found in plants. miR-393 was found to be involved in the resistance to Pseudomonas syringae infection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Natural antimicrobial responses using miRNAs have led to a new area of research in immunology investigating the role of miRNAs in immune response activation.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

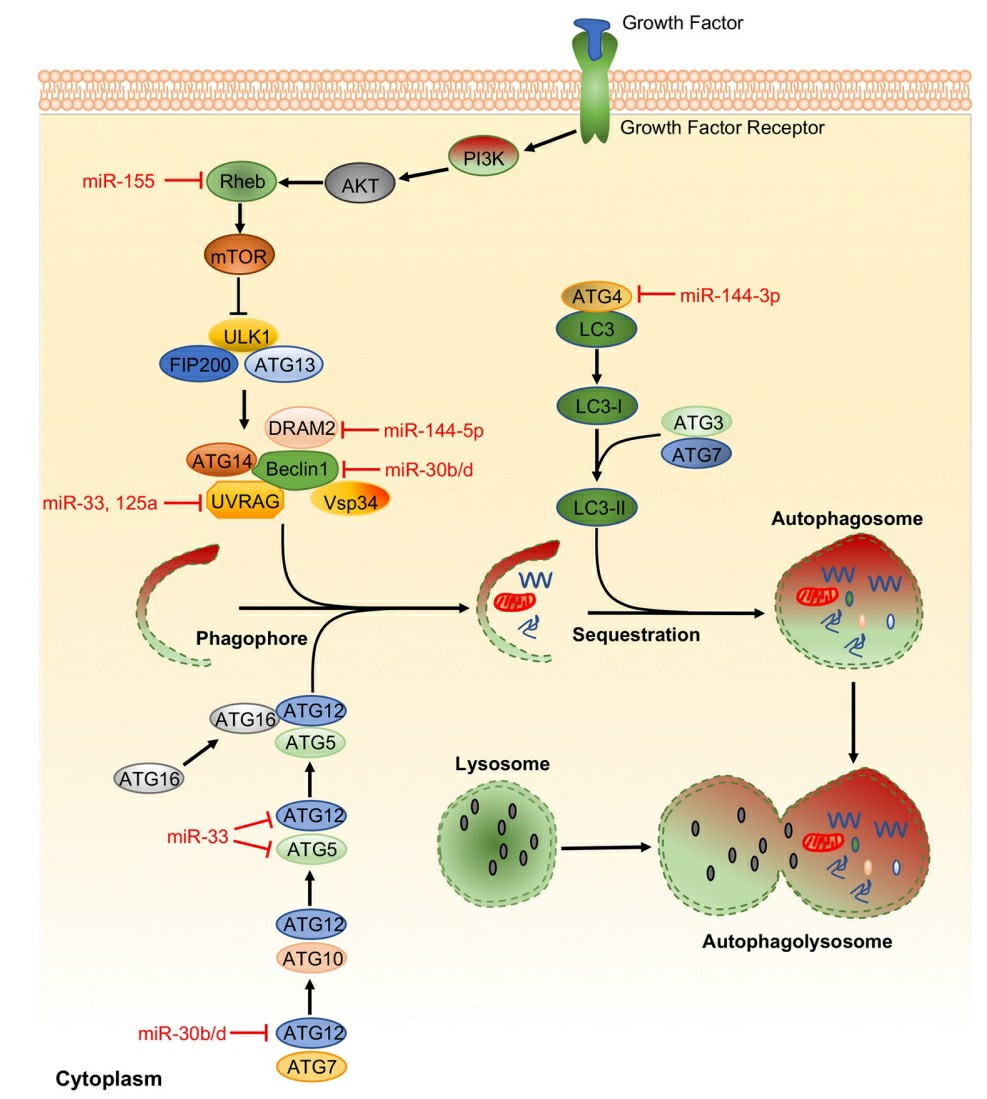

MiRNAs are crucial for the intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis during its infection of the host. Specifically, the miRNAs miR-155 and miR-17-5p represses intracellular colonisation of M. tuberculosis through several pathways that activate the induction of autophagy in macrophages. These two miRNAs activate autophagy and M. tuberculosis clearance by increasing its levels. MiR-155 binds to the 3'UTR region of Rheb and induces the formation of the phagosome, the binding of the phagosome to the lysosome, and the killing of the bacteria. M. tuberculosis also represses other miRNAs to activate the suppression of autophagy. M. tuberculosis upregulates miR-27 during its infection, and miR-27 causes the suppression of the autophagy of Ca2+. Specifically, miR-27 targets the Ca2+ transporter CAC-NA2D3 at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and when it is silenced, it suppresses the production of autophagosome. M. tuberculosis infection of the host cell upregulates miR-1958, which binds to the 3'UTR region of Atg5, whose silencing suppresses the induction of autophagic flux. Finally, miR-18a promotes the infection of M. tuberculosis through the silencing of the ataxia–telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) gene, which decreases the levels of LC3-II in infected cells and halts the process of xenophagy.

Fig. 2 Representative miRNAs in the regulation of autophagy2,6.

Fig. 2 Representative miRNAs in the regulation of autophagy2,6.

- Shigella flexneri and Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium

New microRNAs have also been identified during other bacterial infections. During S. flexneri infection, three miRNAs were identified (miR-3668, miR-4732-5p and miR-6073) that represses infection by targeting the N-WASP gene that is responsible for decreasing bacterial actin-based motility, restricting cell-to-cell spread and attenuating intracellular infection. However, expression of miR-29b-2-5p enhances the formation of filopodia in host cells via UNC-5 Netrin Receptor C (UNC5C) leading to increased bacterial internalization. Despite the similarities between S. flexneri and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, regulation of the expression of these two pathogens elicited different specific miRNAs. miR-let-7i-3p targets the host RGS2 protein and controls the vacuolar trafficking during S. Typhimurium infection and, as a result, suppresses its pathogenesis. In addition, miR-15 family is essential in the pathogenesis of S. Typhimurium since they are downregulated during certain stages of the infection to permit bacterial spreading. Particularly, the miR-15 family delays the cell cycle of the infected cells via repression of the transcription factor E2F1 and repression of cyclin D1.

- Broad-Spectrum miRNAs

Nevertheless, there are miRNAs with broader spectrum antimicrobial activity. MiR-30e-5p reduced the survival of bacterial cells through targeting of SOCS1 and SOCS3 which are important regulators of the innate immune response. Their knockdown reduced bacterial replication. Other miRNAs may target more general regulators of the immune response during infection and may thus have broader spectrum antimicrobial activity. Some miRNAs target signaling pathways activated by TOLL receptors (TLRs). MiR-124 is upregulated during bacterial infection and acts as a negative regulator of the immune response via the TLRs/NK-κB signaling pathway. Hence, anti-miR-124 could act as a broad-spectrum treatment, as was shown for Mycobacterium bovis (BCG). Furthermore, miR-302b expression is induced via TLR2 and the TLR4/ NK-κB pathway during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and is known to enhance the release of cytokines. Also, miRNAs regulate expression of interferon -γ. For example, miR-29 is downregulated during L. monocytogenes and M. bovis infection. Therefore, it would be of interest to test if any of these miRNAs are active against other bacteria.

References

- Mourenza, Álvaro, et al. "Understanding microRNAs in the context of infection to find new treatments against human bacterial pathogens." Antibiotics 11.3 (2022): 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030356.

- Zhou, Xikun, Xuefeng Li, and Min Wu. "miRNAs reshape immunity and inflammatory responses in bacterial infection." Signal transduction and targeted therapy 3.1 (2018): 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-018-0006-9.

- O'Brien, Jacob, et al. "Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation." Frontiers in endocrinology 9 (2018): 402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00402.

- Drury, Ruth E., Daniel O'Connor, and Andrew J. Pollard. "The clinical application of microRNAs in infectious disease." Frontiers in immunology 8 (2017): 1182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01182.

- SiouNing, Aileen See, et al. "MicroRNA Regulation in Infectious diseases and its potential as a Biosensor in Future Aquaculture Industry: a review." Molecules 28.11 (2023): 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28114357.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.