Silencing the Future-A Cutting-Edge Comparison of miRNA and shRNA Technologies

The RNAi Revolution: Three Pathways to Gene Silencing

The new RNAi technology now presents three pathways of gene silencing: miRNA, siRNA, and shRNA. The first is the naturally occurring miRNA pathway, which down-regulates mRNA expression via partial complementarity. These small, non-coding RNAs play an essential role in normal cellular functions and also contribute to pathophysiology. Therefore, they are the ideal targets for gene therapy. siRNA and shRNA are two exogenous methods for knockdown of specific genes, which have different purposes and different characteristics. siRNA is typically introduced exogenously for fast and temporary knockdown and is useful for short-term study and fast validation of gene function. However, the target mRNA sequence must be carefully designed to avoid nonspecific binding. Additionally, siRNA is rapidly degraded in the cytoplasm and only lasts for several hours. Therefore, for long-term or persistent expression, siRNA must be injected multiple times. Alternative approaches to improve delivery of siRNA include novel polymer nanoparticles and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). However, shRNA can persistently knockdown target genes and has been proven to be ideal for long term applications including for chronic disease treatment and/or stable cell lines and animal models. Insertion of the shRNA construct may result in insertional mutagenesis; however, this is not an issue with the use of self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviruses.

Molecular Showdown: Design and Mechanism

miRNA: The Body's Natural Regulator

- Biogenesis: From Nucleus to Functional RISC Complex

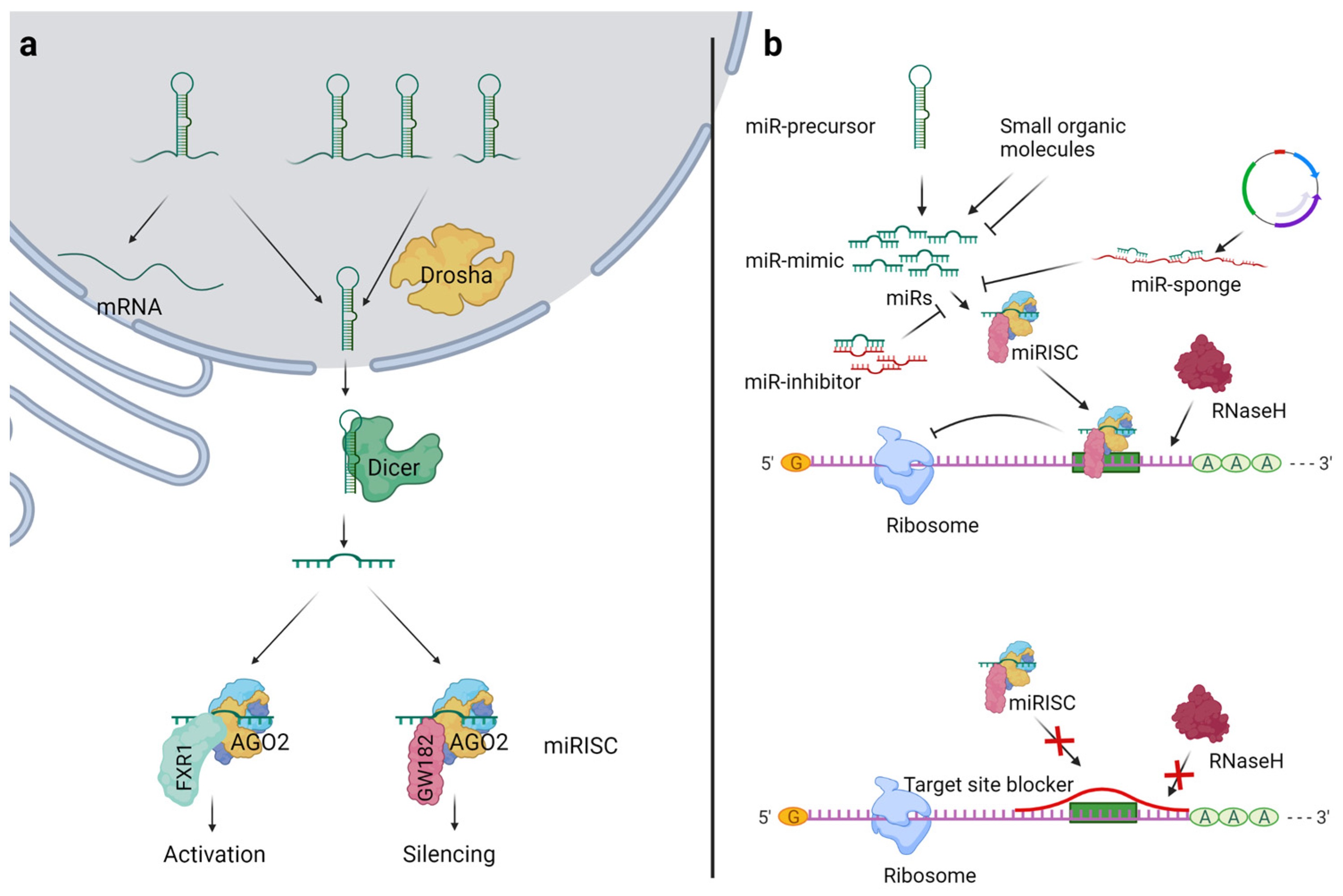

miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II or III in the nucleus as long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs). They are processed into precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) by Drosha/DGCR8. Pre-miRNAs are then exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin-5 in a RanGTP-dependent manner. Dicer processes them into miRNA duplexes. The functional strand (guide strand) of the duplex is loaded onto Argonaute (AGO) protein to form miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) and targets specific mRNAs for degradation or repression.

Fig. 1 Overview of miR biogenesis and general strategies for miR modulation1,5.

Fig. 1 Overview of miR biogenesis and general strategies for miR modulation1,5.

- The "Seed Sequence" Advantage: One miRNA to Rule Them All

The seed sequence (nucleotides 2-8) is important for target recognition. This short region allows miRNAs to target many mRNAs with only partial complementarity. This makes it possible for miRNAs to control entire gene networks. The ability of a miRNA to target many targets at once means that they can play a role in fine-tuning gene expression in many biological processes. One miRNA can regulate multiple genes involved in inflammation, proliferation, and differentiation.

- When Subtlety Matters: Fine-Tuning vs Complete Silencing

This mode of regulation allows miRNAs to silence target mRNAs in a highly regulated manner. miRNAs primarily act to induce translational repression rather than mRNA degradation. For example, in the context of GI diseases, miRNAs are able to silence pro-inflammatory cytokines, without completely eliminating them. This is important in maintaining homeostasis.

shRNA: another regulator

- DNA Weaponry: Viral Vector Delivery Systems

shRNAs are designed to fold into a hairpin structure. Typically they are expressed using a DNA vector with an RNA polymerase III promoter (e.g. U6 or H1). The vector is then introduced using a viral system such as lentivirus or AAV. Viral systems are capable of integrating into the host genome. These viruses are stable and allow for long-term expression. For example, lentiviral vectors containing shRNA constructs have been used to knock down target genes for months in animal models of chronic GI diseases.

- Endurance Test: Weeks to Months of Continuous Silencing

The integrated shRNA constructs stay in the host genome for long periods of time. This is ideal for long-term treatment of chronic diseases such as IBD or GI cancers. The caveat is that long-term expression may carry the risk of insertional mutagenesis where an integration event may knock out an endogenous gene or regulatory element.

- The Dark Side: Genomic Integration Risks and Solutions

Because of the fact that long term gene expression can cause insertional mutagenesis, it is possible for integration of shRNA constructs to induce genetic alterations in host tissues. This is especially relevant in tissues with high cellular turnover (like the GI tract). However, this issue can be mitigated by using safety modified viral vectors (e.g. SIN lentiviral vectors). Safety modified viral vectors contain an inactivated promoter that will inactivate itself after integration, thus lowering the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

Delivery Wars: Getting RNAi Where It Needs to Go

- Mimics vs Inhibitors: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Based on the RNA interference technology, miRNA-based therapeutics can be generally classified into two types. MiRNA mimics increases the expression and function of endogenous miRNAs, while miRNA inhibitors, like antagomirs, decreases the expression and function of endogenous miRNAs. Which type of miRNA therapeutics should be used for a certain disease target is dependent on the type of disease target, that is, if the disease is caused by the overexpression of a tumor-suppressive miRNA, then the type of miRNA mimics is used; if the disease is caused by the overexpression of an oncogenic miRNA, then the type of miRNA inhibitors is used.

- Preventing the Sponge Effect

Besides, another problem of miRNA therapy is the so-called sponge effect. When miRNA mimics and inhibitors are delivered into a cell, they will sponge the native miRNAs in the process, and cause downstream effect which are not what we expect. Modified nucleotides could be used in miRNA mimics and inhibitors to improve the specificity of the miRNAs and avoid the sponge effect of native miRNAs. Computer-aided methods andin vivo validation could be used to screen the possible targets and test the sponge effect in vivo.

- Tissue-specific Targeting

The primary goal of successful delivery of miRNA-based therapeutics is tissue-specific targeting. There are many different delivery systems for miRNA, including viral vectors and non-viral carriers. Viral vectors like AAVs and lentiviral vectors have high transduction efficiency, but they can induce immune reaction that could decrease the therapeutic effect. Non-viral delivery systems like lipid nanoparticles and exosomes could be a biocompatible and highly efficient substitute. Exosomes isolated from mesenchymal stem cells can directly deliver miRNAs to glioblastoma cells, inhibit tumor growth and positively regulate the immune response.

shRNA Vector Evolution

- AAV vs Lentivirus: Comparison of Viral Brothers

In the choice of the delivery system to carry shRNA construct, there is a tradeoff between AAV and lentivirus. AAVs are less immunogenic and have a broader range of transduction efficiency. Thus, if long-term expression is required, AAVs could be the best choice. However, lentiviral vectors transduce more efficiently and integrate stably into the genome. Lentiviral vectors are susceptible to insertional mutagenesis, but this can be prevented by using SIN lentiviral vectors. Therefore, the choice between AAV or lentivirus depends on the purpose of the therapy.

- Promoter-based System: Smart Switches

One can control the expression of shRNAs at a certain time point with specific stimulus (e.g. small molecules or environmental signals). Inducible promoters can be engineered into shRNA constructs and they are designed to regulate the expression of shRNAs upon the addition of stimuli. Such inducible systems may be highly beneficial in certain scenarios where the timing of knockdown is critical, e.g. during development stages or a disease process.

- Safer system: Genotoxicity Risks Minimized

The major concern for shRNA-based therapy is the risks of genotoxicity. Since the viral vector inserts into the host genome at random positions, the shRNA construct may insert into a gene with a risk of mutagenesis. It has been reported that a shRNA construct inserted into the host gene and induced unexpected mutations. Therefore, safer vector design and alternative delivery methods are being developed. For example, SIN lentiviral vectors have been engineered to shut down their own promoter upon integration to avoid the process of mutagenesis. Non-viral delivery methods (e.g. transposon-based methods) are also being investigated as alternatives to viral vectors. These new technologies aim to make shRNA therapies safer while retaining their potential in long-term knockdown.

shRNA vs miRNA: Clinical Battlegrounds

miRNA Therapeutics: Natural Remedies

- Replacement Therapy: Tumor Suppressor miRNAs Restored

For cancer, some other than tumor suppressor miRNAs, some oncogenic miRNAs that are overexpressed in cancer can be replaced by mimics to inhibit tumorigenesis. For example, as one of the tumor suppressor miRNAs, miR-34a is commonly downregulated in various cancers. Restoring miR-34a using mimics inhibits tumor growth and multiple oncogenes. Another example is to restore miR-29 using mimics, which is downregulated in fibrotic diseases. It was found that restoring miR-29 using mimics can suppress collagen production and fibrosis.

- Anti-miRs: Oncogenic miRNAs (Oncomirs) Inhibited

For anti-miRs, some oncogenic miRNAs that are overexpressed in diseases can be inhibited by anti-miRs. For example, as one of the oncogenic miRNAs, miR-21 is overexpressed in various cancers and fibrotic diseases. Anti-miR-21 targeting miR-21 can inhibit fibrosis in Alport syndrome in the clinic. Another example is anti-miR-122, which can target miR-122, which is a liver-specific miRNA involved in HCV replication.

- The Inflammation Tightrope: Inflammation in Check

As some miRNAs regulate the immune system, miRNAs are attractive therapeutic targets for inflammation. For example, miR-155 is overexpressed in inflammation. Anti-miR-155 therapies targeting miR-155 can suppress inflammation. However, miRNAs that regulate the immune system should be avoided because a strong anti-miR therapy for miRNAs that play a role in the immune system may result in immunodeficiency.

shRNA's Niche Dominance

- Supercharging Cancer therapy

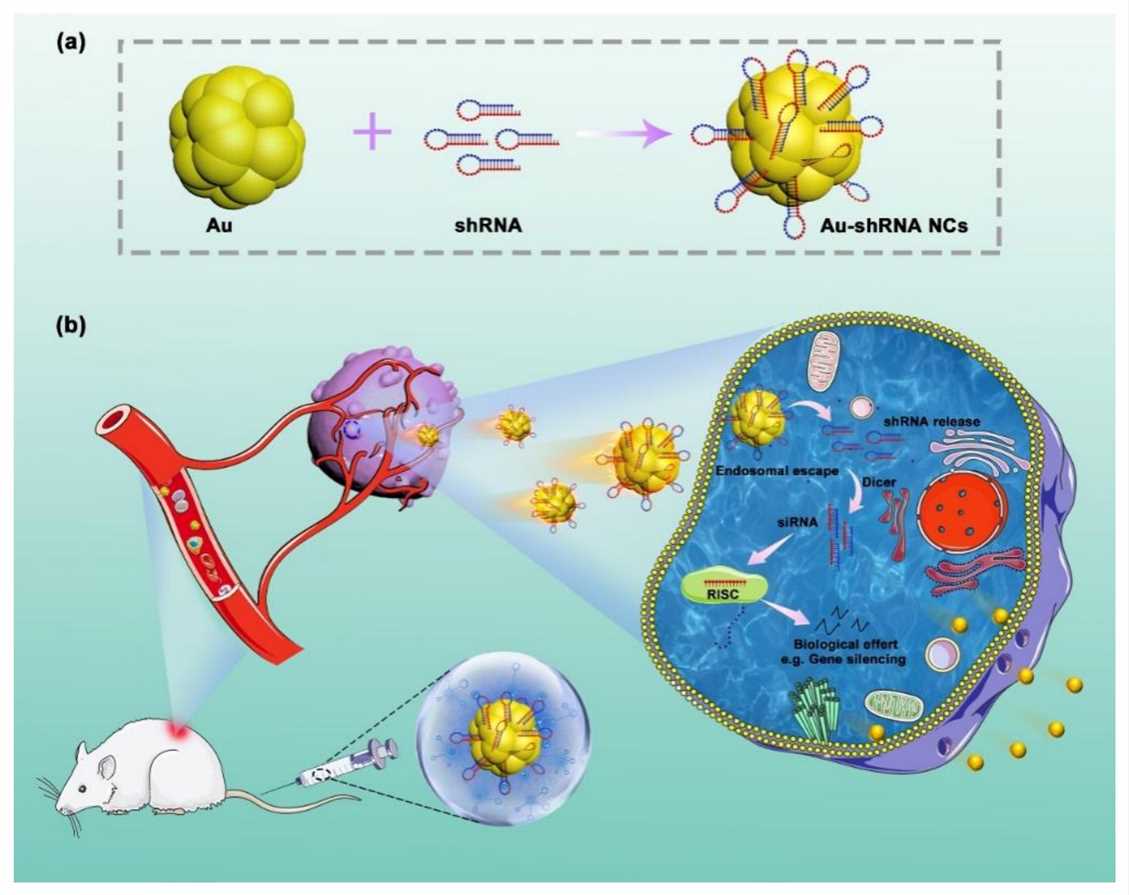

SKOV3 cells transfected with an RNAi plasmid against survivin showed increased apoptosis and slower growth. At the molecular level, these cells also showed reduced expression of survivin. Nude mice inoculated with SKOV3 cells developed cancers, and treatment with shRNA targeting survivin significantly inhibited the growth of these cancers without any side effects. The Nrf2-dependent defensive system was probably fully activated in cervical tumor tissues. Knockdown of endogenous Nrf2 by shRNA led to a global reduction in the expression of Nrf2-regulated genes. The decrease in expression levels increased the chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptotic death in CaSki cells with a reduced cellular glutathione level. Moreover, the combination of cisplatin treatment and Nrf2 knockdown significantly suppressed tumor growth in vivo. One research put forward a new method for shRNA delivery, imaging, and treatment of cancers using bio-responsive self-assembled fluorescent Au–shRNA nanocomplex. It has many advantages such as high targeting efficiency and high biocompatibility in precise tumor bioimaging and drug delivery systems. The advantages in regulating cytotoxicity, cellular uptake, endosomal escape, and shRNA transfection efficiency are probably attributed to the balance between modules with different functions (e.g., electrostatic charge and pH). In situ self-assembled Au–shRNA nanocomplex can protect shRNA from external effects, realize cellular uptake, and effective endosomal escape.

Fig. 2 Schematic illustration of the in situ bio-self-assembled fluorescent Au–shRNA NCs to achieve biological effects for cancer imaging and theranostics2,5.

Fig. 2 Schematic illustration of the in situ bio-self-assembled fluorescent Au–shRNA NCs to achieve biological effects for cancer imaging and theranostics2,5.

The Toxicity Tightrope

- miRNA: The Butterfly Effect of Network Perturbation

miRNAs operate as a part of the complex gene regulatory network. As a result, miRNAs' contribution to multiple pathways is a double-edged sword. On the other hand, small perturbations of only a few genes could have knockdown effects on several other genes in different pathways. For example, miR-155 is highly upregulated in several inflammatory conditions and regulates expression of numerous immune related genes. Therefore, inhibition of miR-155 with anti-miR treatment could cause the unwanted knockdown of other genes that are regulated by miR-155. Similarly, miR-21 is upregulated in fibrotic diseases and cancer. Thus, inhibition of miR-21 could reduce fibrosis and tumor growth but cause the unwanted knockdown of other genes regulated by miR-21. In both examples, the complexity of the miRNA regulatory network must be considered in the potential side effects of anti-miR treatment.

- shRNA: The Genomic Integration Gamble

The main benefit of shRNA is the long-term, sustained knockdown achieved through genomic integration. The long-term nature of knockdown is also the source of the potential for unwanted side effects, as integrating the shRNA construct can interfere with endogenous genes or regulatory elements. One method to reduce the risks of insertional mutagenesis is the use of SIN lentiviral vectors. With SIN lentiviral vectors, the promoter that was used to integrate them has been inactivated. By inactivating the promoter, the insertional mutagenesis risk is reduced. Non-viral delivery systems, such as transposon-based delivery systems, are also being investigated. These methods do not integrate the shRNA construct into the host genome, rather the shRNA construct is incorporated into the host genome by a transposon, eliminating the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

References

- Momin, Mohammad Yahya, et al. "The challenges and opportunities in the development of MicroRNA therapeutics: a multidisciplinary viewpoint." Cells 10.11 (2021): 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113097.

- Cai, Weijuan, et al. "Intelligent Bio-Responsive Fluorescent Au–shRNA Complexes for Regulated Autophagy and Effective Cancer Bioimaging and Therapeutics." Biosensors 11.11 (2021): 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11110425.

- O'Brien, Jacob, et al. "Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation." Frontiers in endocrinology 9 (2018): 402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00402.

- Oliver, David, et al. "Identification of novel cancer therapeutic targets using a designed and pooled shRNA library screen." Scientific reports 7.1 (2017): 43023. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43023.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.