The Integration Challenge-Lentivirus Vectors in Preclinical Gene Therapy

Lentiviral vector gene therapy

The retroviridae virus family has given rise to lentiviral vectors (LVVs), which researchers frequently derive from HIV-1 and use in experimental research alongside therapeutic interventions. Researchers developed alternative LVVs by utilizing source viruses which include the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), the feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), and the equine infectious anaemia virus (EIAV). LVVs provide an effective approach to modify eukaryotic cells because they use the native ability of retroviruses to insert their genetic material into the host cell genome. LVVs hold the ability to carry genes up to 10 kb and deliver the gene of interest for stable transduction as the "expression cassette". The lentiviral vector genome contains three structural genes that perform identical functions in both wild-type viruses and engineered vectors. The retroviral genome contains three essential structural genes which are named group-specific-antigen (gag), polymerase (pol), and envelope (env).

Historical context and development of lentivirus vectors

- Early description of Lentivirus

The initial historical description of lentiviral disease originated from the study of a progressive disorder found in Icelandic sheep flocks during the 1950s. The disease presented as a severe pneumo-encephalopathy which took its name from the virus that caused it. Lentiviral infections produce different pathologies yet display multiple shared characteristics. De novo infection progresses from an initial transient acute viral replication stage to a chronic phase. Most lentiviral pathogenic mechanisms exhibit a prolonged chronic phase with minimal viral replication as demonstrated by many conditions including severe immunodeficiency in primates and felines and synovitis in CAEV-infected goats as well as severe pneumo-encephalopathy in VMV-infected sheep.

- Lentivirus vector development

LVVs have undergone substantial development from their creation due to the necessity for effective and secure gene therapy delivery systems. Investigating lentiviruses lays the groundwork for vector development with a primary focus on HIV analysis. The initial scientific studies investigated lentiviruses since they possess the unique ability to infect both dividing and non-dividing cells unlike other retroviral vectors. Scientists developed the initial LVVs from HIV-1 through the deletion of non-essential viral genes which produced replication-incompetent vectors that ensure safety by blocking viral replication. The development of LVVs has achieved significant advancements which improved both their safety and effectiveness throughout time. The design of self-inactivating (SIN) vectors represents a key advancement because modifying viral LTRs decreases the risk of insertional mutagenesis. The implementation of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) as an alternative envelope protein has led to better vector stability and a wider selection of targetable host cells.

Integration Mechanism of Lentivirus Vectors

LVVs originate from retroviruses like HIV which gives them the unique ability to incorporate their genetic material directly into the genomes of host cells. LVVs possess an integration mechanism which facilitates prolonged therapeutic gene expression thereby enhancing their gene therapy application effectiveness.

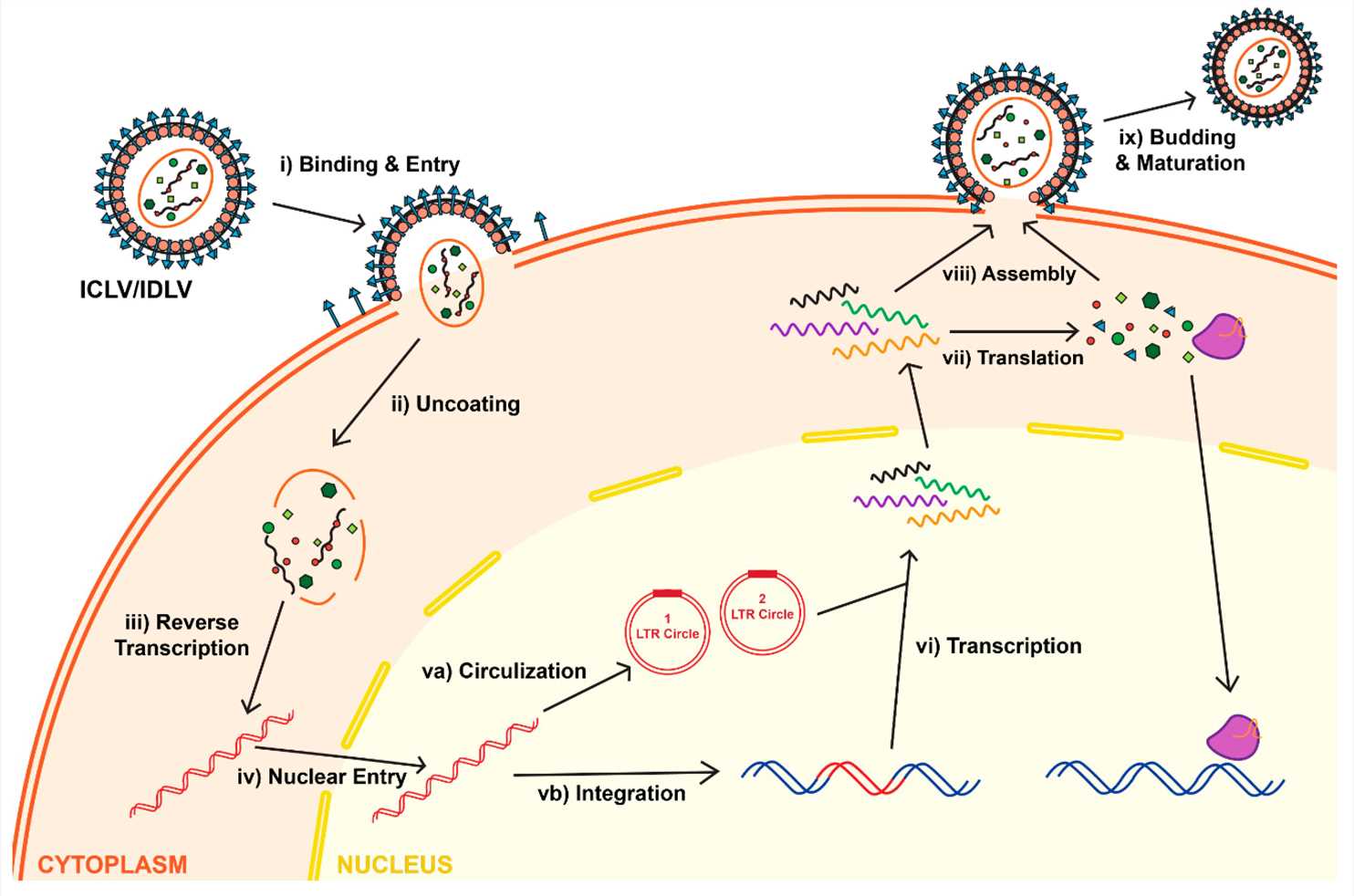

- Entry and Reverse Transcription

The LVV begins the integration process as soon as it penetrates its target cell. The vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) enables viral envelopes to bind and fuse with host cell membranes facilitating viral core entry into the cell. After entering the host cell the viral reverse transcriptase enzyme converts the viral RNA genome into double-stranded DNA through reverse transcription. The pre-integration complex (PIC), which is a linear DNA molecule, forms during a reaction in the cytoplasm.

- Nuclear Import

The pre-integration complex moves into the host cell nucleus carrying viral DNA together with proteins like integrase. The viral DNA needs to enter the nucleus because this process makes it possible for the DNA to access the host genome. The PIC gains access to the nucleus either by passing through nuclear pores or by commandeering the cell's nuclear import systems.

- Integration into the Host Genome

When viral DNA reaches the nucleus the viral integrase enzyme enables its incorporation into the host genome. The viral integrase enzyme recognizes long terminal repeats (LTRs) located at the ends of the viral DNA to trigger the integration process. The selection of the integration site within the host genome occurs through a semi-random process yet certain regions may become preferred targets because of their chromatin structure and accessibility.

- Post-Integration Events

Once integrated, the viral DNA establishes itself as a permanent fixture in the host genome. Once integrated into the host genome as a provirus the viral DNA becomes available for transcription by the host's transcriptional machinery which results in therapeutic gene expression. Through stable integration the therapeutic gene incorporates into the host genome and continues to be expressed in daughter cells during cell division.

Fig.1 Life cycle of lentiviruses for both Integrase-Competent Lentivirus (ICLV) and Integrase-Deficient Lentivirus (IDLV)1.

Fig.1 Life cycle of lentiviruses for both Integrase-Competent Lentivirus (ICLV) and Integrase-Deficient Lentivirus (IDLV)1.

Preclinical Models for Studying Integration of Lentivirus Vectors

Preclinical models represent crucial research instruments through which scientists can understand the integration process of LVVs into host genomes which lays the groundwork for developing safe and effective gene therapies. Scientists study LVV integration mechanisms through in vitro and in vivo models while evaluating safety and efficacy and investigating insertional mutagenesis risks.

- In Vivo Models

Studying integration preferences of LVVs has heavily relied upon transgenic mouse models as experimental tools. Researchers inject LVVs into early-stage embryos with these models to study how the vectors integrate into different tissues and organs. An investigation into proviral integration sites within transgenic rats produced through LVVs revealed specific integration preferences during distinct embryonic developmental stages. Researchers mapped 112 independent integration sites from 43 transgenic founder mice which revealed that lentiviral integration sites display non-random distribution patterns across the genome and show specific preferences.

Liver disease mouse models serve as an essential tool for examining how LVVs integrate and cause hepatotoxicity. A research study assessed the therapeutic potential and safety profile of a lentiviral vector containing fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH) when introduced into healthy mice and mice with liver injuries. The study results showed the lentiviral vector integrated stably into hepatocytes and cured the hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (HT1) model while also generating important hepatotoxicity data.

- In Vitro Models

Researchers utilize human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells among other in vitro cell culture systems to examine how LVVs integrate. These systems provide a controlled environment to study how different cellular elements contribute to the integration process. Research performed with HEK293T cells showed that LEDGF/p75, a host factor, plays a significant role in determining where LVVs integrate. Researchers mapped lentivirus integration sites using ovine cell lines depleted of HRP2 and/or LEDGF/p75 to understand how these host factors influence integration site selection.

Researchers apply primary cell cultures like hepatocytes and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to examine how LVVs integrate into relevant cell types. Researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a lentiviral vector for β-thalassemia treatment using primary hepatocytes which showed stable genetic integration and sustained therapeutic gene expression. Research has utilized HSCs to analyze how LVVs integrate into cells and express in hematopoietic disorders.

Disadvantages and Risks of Lentiviral Vectors in Preclinical Models

- Insertional Mutagenesis and Oncogenic Transformation

LVVs can integrate into the host genome to disrupt normal genes or activate oncogenes which could lead to malignant transformation. Rapid cell division increases the danger of using LVVs because they tend to cause mutations when they insert into the host genome. Essential genes and regulatory elements may experience undesired interference due to the random integration patterns of LVVs. The unpredictable integration pattern increases the likelihood of insertional mutagenesis.

- Limited Vector Capacity

LVVs have a genetic payload capacity limit of 8 to 10 kilobases. The limited capacity of LVVs to hold genetic material creates significant obstacles for researchers who need to deliver large genetic sequences or multiple genes simultaneously.

- Immunogenicity and Safety Concerns

LVVs trigger immune responses that decrease therapeutic effectiveness and create potential dangers to the treated individual. Transduced cells can be eliminated by the immune response which diminishes both the longevity and potency of gene expression. Accidental exposure presents a danger during the production and management stages because LVVs exhibit high rates of mutation and recombination. The use of LVVs requires strict biosafety protocols and comprehensive risk evaluations.

- Transduction Efficiency and Expression Levels

Different target tissues and cell types result in variable transduction efficiencies. LVVs demonstrate lower transduction efficiency in cardiac muscle compared to adenovirus-associated virus (AAV) vectors. The risk of insertional mutagenesis from non-integrating lentiviral vectors (NILVs) decreases but their transgene expression levels typically fall short of those achieved by integrating vectors.

- Long-Term Stability and Persistence

Loss of Episomal Vectors: The episomal DNA of NILVs gets lost in rapidly dividing cells which causes diminished long-term therapeutic gene expression.

Overcoming Challenges in Integration Management

- Addressing Insertional Mutagenesis Risks

SIN LVVs were developed to reduce the risk of insertional mutagenesis. By eliminating viral enhancer and promoter elements from the 3' LTR these vectors avoid activation of adjacent oncogenes. The utilization of SIN vectors substantially lowers the risk of events associated with insertional mutagenesis without compromising their ability to deliver genes and express them efficiently.

A method to reduce insertional mutagenesis involves steering LVVs integration toward predetermined genomic safe harbor locations. With the aid of CRISPR/Cas9 technologies researchers can guide viral DNA integration to genome areas that minimize the disruption of vital genes and prevent oncogene activation. The technique improves the LVV safety profile by reducing the chances of unintended genetic disruptions.

- Ensuring Consistent and Reliable Integration Across Models

Standardized in vivo and in vitro systems represent a critical requirement for achieving consistent and reliable integration across different preclinical models. Researchers study integration processes in living organisms by using transgenic mice together with liver-injury mouse models which reveal long-term outcomes and potential hazards. Cell culture systems and primary cell cultures as in vitro models provide the ability to perform controlled experiments which reveal molecular integration mechanisms. The standardization of these models enables researchers to produce data that can be reproduced and compared across various studies.

The study of host factors' influence on integration site selection allows scientists to develop methods that control these elements to modify integration outcomes. Artificial peptide-LEDGF/p75 hybrids increase integration safety by raising the percentage of integrations in safe harbor sites. Researchers can achieve more consistent integration results across different models by controlling host factors.

- Development of Non-Integrative Lentiviral Vectors

Research laboratories have developed NILVs as an alternative approach to avoid integration-related issues. Vectors with mutations that deactivate Integrase prevent viral DNA from integrating. In the initial infection stages viral DNA integrates into the host genome or remains as episomal DNA structures containing one or two long terminal repeats known as 1LTRs and 2LTRs circles. The nuclear formation of these episomes happens when viral ends connect through cellular ligases to create 2LTRs or when they recombine to form 1LTRs. These two forms of viral DNA maintain their ability to express genes both during natural HIV-1 infection and when used in lentiviral vector systems. The absence of an origin of replication causes these episomes to diminish gradually throughout cell division. Viral DNA episomes maintain stability within cells that do not divide, which serve as the principal targets for lentiviral transduction methods. NILVs establish a secure environment for gene delivery within cells that do not divide or those that have undergone differentiation.

References

- Dong, W.; Kantor, B. Lentiviral Vectors for Delivery of Gene-Editing Systems Based on CRISPR/Cas: Current State and Perspectives. Viruses. 2021, 13, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13071288.

- Gurumoorthy, N.; Nordin, F.; Tye, G.J.; Wan Kamarul Zaman, W.S.; Ng, M.H. Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vectors in Clinical Applications: A Glance Through.Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10010107.

- Perry, C.; Rayat, A.C.M.E. Lentiviral Vector Bioprocessing. Viruses. 2021, 13, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13020268.

- Suleman, S.; Payne, A.; Bowden, J. HIV- 1 lentivirus tethering to the genome is associated with transcription factor binding sites found in genes that favour virus survival. Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 720–729 (). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-022-00335-4.

- Apolonia, L. The Old and the New: Prospects for Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vector Technology. Viruses. 2020, 12, 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12101103.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.