From Virus to Vaccine: The Science Behind HPV Prevention

Human papillomavirus (HPV) remains one of the most prevalent viral infections worldwide, yet its role as a "silent threat" often goes unrecognized until serious health issues arise. Behind the development of HPV vaccines lies a fascinating interplay of immunology, molecular biology, and public health science. This article explores the journey from understanding the virus to designing vaccines that protect against its harmful effects, demystifying the science that safeguards millions of lives.

HPV: A Common yet Concealed Threat

What is HPV?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a diverse group of viruses transmitted through close skin-to-skin contact. While many infections resolve on their own without symptoms, certain "high-risk" strains can persist, leading to severe health consequences. Over time, chronic infection with these high-risk types may cause precancerous changes in cells, potentially progressing to cancers of the cervix, anus, mouth, and throat. This ability to quietly damage cells over years earns HPV its reputation as a "silent killer."

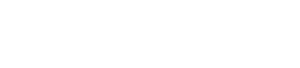

How HPV Infects and Harms Cells

The virus's danger lies in its infection mechanism. Upon contact, HPV binds to specific receptors on the surface of host cells, typically in the epithelial tissues of the skin or mucous membranes. Once inside, it hijacks the cell's machinery to replicate its genetic material. Unlike some viruses that kill cells quickly, HPV disrupts the normal cycle of cell growth and division. It interferes with genes that regulate cell multiplication, leading to uncontrolled growth—a hallmark of cancer. This slow, stealthy process can take years, making early intervention critical.

Fig.1 The Pathogenic Pathway of HPV Infection.1,2

Fig.1 The Pathogenic Pathway of HPV Infection.1,2

How the Immune System Fights Back

The human immune system is a sophisticated defense network, equipped to recognize and eliminate foreign invaders like HPV. Its response unfolds in two key phases:

Recognition and Activation

When HPV enters the body, immune cells called dendritic cells identify its "non-self" components—such as unique viral proteins. These dendritic cells then alert other immune cells, triggering a coordinated attack.

Humoral and Cellular Immunity

The immune response has two main branches. Humoral immunity involves B cells, which produce antibodies—proteins designed to target specific viral components. These antibodies act like molecular blockers, binding to HPV and preventing it from entering healthy cells. Cellular immunity, on the other hand, relies on T cells, which hunt down and destroy cells already infected with the virus, limiting its spread.

The Power of Neutralizing Antibodies

Antibodies are particularly crucial in fighting HPV. By attaching to the virus's surface proteins, they "neutralize" it, rendering it unable to infect new cells. This neutralization is the immune system's first line of defense, but in natural infections, it may develop too slowly to prevent long-term damage. This is where vaccines step in.

Services you may interested in

Designing Vaccines: Training the Immune System

Vaccines work by "teaching" the immune system to recognize and respond to a pathogen before a real infection occurs. For HPV, this training relies on a clever biological trick: mimicking the virus without its ability to cause harm.

Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): Safe Mimics

Preventive HPV vaccines are crafted using genetic engineering to produce "virus-like particles" (VLPs). These particles are made from a key viral protein, known as L1, which forms the outer shell of the virus. When expressed in lab-grown cells, L1 proteins self-assemble into structures that look nearly identical to the actual HPV virus under a microscope. Crucially, however, VLPs contain no viral genetic material, meaning they cannot replicate or cause infection.

Priming the Immune Response

When the vaccine is administered, these VLPs are detected by the immune system as foreign invaders. Dendritic cells pick up the VLPs, present their proteins to B cells, and trigger the production of antibodies specifically targeting HPV. Over time, the immune system also develops memory cells—long-lived B and T cells that "remember" the virus's structure. If a real HPV infection occurs later, these memory cells spring into action, producing a rapid, robust antibody response to neutralize the virus before it can cause damage.

Immunological Advantages: Stopping Infection at the Source

The true power of HPV vaccines lies in their ability to block infection entirely, rather than treating it once it has taken hold.

A Preemptive Antibody Barrier

Vaccine-induced antibodies circulate in the bloodstream and mucosal tissues—areas where HPV typically enters the body. When the real virus attempts to infect cells, these antibodies immediately bind to it, preventing it from attaching to cell receptors or entering cells. This preemptive strike stops the infection in its tracks, eliminating the risk of precancerous changes or cancer development.

Why Prevention Matters

Unlike treatments that address existing infections, preventive vaccines interrupt the disease process at the earliest stage. For HPV, which can cause irreversible cell damage over time, this is critical. By establishing immunity before exposure, vaccines drastically reduce the likelihood of developing HPV-related cancers and other diseases, offering long-term protection.

Scientific Evaluation: Ensuring Safety and Efficacy

Before any vaccine reaches the public, it undergoes rigorous testing through clinical trials, a multi-stage process designed to assess its safety and effectiveness.

The Stages of Clinical Trials

HPV vaccine development follows three key phases of trials. Phase I focuses on safety, testing different doses in small groups to identify potential side effects. Phase II expands to larger groups, evaluating how well the vaccine stimulates an immune response (measured by antibody levels) and refining dosage. Phase III is the largest and most critical, involving thousands of participants to compare disease rates between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. This phase confirms whether the vaccine actually prevents HPV infections, precancerous lesions, or other related conditions.

Key Trial Endpoints

Researchers track several critical outcomes to determine a vaccine's success. These include:

- Disease incidence: Whether vaccinated individuals develop fewer precancerous lesions or persistent HPV infections compared to controls.

- Antibody titers: The level of neutralizing antibodies produced, which indicates the strength of the immune response.

- Safety profiles: The frequency and severity of side effects, ensuring the vaccine's benefits far outweigh any risks.

These stringent evaluations ensure that approved vaccines are both safe and effective, providing confidence to healthcare providers and the public.

Addressing Controversies and Challenges

Like all medical interventions, HPV vaccines have faced questions, but scientific evidence addresses these concerns.

Safety and Side Effects

Reported side effects of HPV vaccines are generally mild and temporary, such as redness, swelling, or soreness at the injection site. More serious adverse events are extremely rare and, in large-scale studies, have not been linked to the vaccine itself. Long-term safety monitoring confirms that HPV vaccines do not cause chronic health issues.

Coverage and Individual Variability

Different vaccines target varying numbers of HPV strains, with some protecting against more high-risk types than others. This variability means coverage depends on the vaccine used. Additionally, individual immune responses can differ—some people may produce higher antibody levels than others, though even lower responses typically provide sufficient protection. Ongoing research aims to understand these differences to improve vaccine design.

Future Frontiers: Advancing HPV Prevention

Science continues to push the boundaries of HPV vaccine development and accessibility.

Next-Generation Vaccines

Researchers are working on broader-spectrum vaccines that target more HPV strains, reducing the risk of infections from less common but still harmful types. Personalized vaccines, tailored to an individual's genetic makeup or regional HPV prevalence, are also under exploration, potentially enhancing effectiveness in diverse populations.

Global Accessibility

A major challenge remains ensuring equitable access to HPV vaccines, particularly in low-income countries where cervical cancer rates are highest. Efforts to reduce costs, expand vaccination programs, and integrate HPV prevention into existing healthcare systems are critical to closing this gap. International collaborations and advocacy aim to make these life-saving vaccines available to all who need them.

The development of HPV vaccines represents a triumph of interdisciplinary science, combining immunology, molecular biology, and public health research. By harnessing the immune system's ability to learn and defend, these vaccines have transformed the fight against HPV-related diseases, preventing countless cancers and saving lives.

As science advances, we move closer to a world where HPV-related cancers are rare. With continued research, improved accessibility, and public trust in scientific progress, the vision of a healthier future—protected by the power of vaccines—becomes increasingly achievable. In the end, it is science that stands as our most reliable shield against invisible threats like HPV.

Ready to advance your HPV vaccine project? Creative Biolabs provides a fully integrated, one-stop service to bring your concepts to the preclinical stage. Our expert team supports every phase, including optimized antigen design, vector construction, and comprehensive preclinical safety and efficacy assessment. Partner with us to achieve your development goals efficiently. Contact our specialists now for a detailed consultation.

If you want to learn more about the hpv vaccine, please refer to:

The Molecular Architecture of HPV: Decoding the L1 Capsid Protein

Beyond Prevention: The Science of Therapeutic HPV Vaccines Explained

HPV E6/E7 Oncoproteins: Key in Therapeutic Vaccine Development

HPV Vaccine Development Timeline: From Lab Research to Clinical Application

Ready-to-Use HPV Antibodies

| CAT | Product Name | Target | Type | Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAnt-Wyb178 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2a, 3.3 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb179 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG1, 3.8 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb180 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2a, 3.4 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb181 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E6, IgG1-κ, 4.8 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb182 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E6, IgG1-κ, 1.01 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb183 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (L1, IgG1, 3.0 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb184 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (L1, IgG2a-κ, 4.5 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb185 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (L1, IgG2a-κ, 3.3 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb186 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2b, 4.3 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb187 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2a, 4.4 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb188 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG1, 3.0 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb189 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2a, 5.1 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb190 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (E7, IgG2a, 4.7 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb191 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (Clone: VA-1870H, IgG1-κ, 1 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb192 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (Clone: VA-187H, IgG1-κ, 1 mg/ML) | Human Papillomavirus | Antibody | Inquiry |

| VAnt-Wyb193 | HPV Monoclonal Antibody (Clone: VA-187H, IgG1, 7.4 mg/ML) | Antibody | Inquiry |

Browse our HPV Antigen Products

→Human Papillomavirus Antigens

Need a custom solution? If our off-the-shelf products aren't a perfect fit, we can create one for you. Contact us to design a product that precisely matches your experimental demands.

References

- Włoszek, Emilia, et al. "HPV and Cervical Cancer—Biology, Prevention, and Treatment Updates." Current Oncology 32.3 (2025): 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030122

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

All of our products can only be used for research purposes. These vaccine ingredients CANNOT be used directly on humans or animals.