In recent decades, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the antitumor function of immune cells has rapidly progressed. t=This has led to the emergence of adoptive cell therapy (ACT) as a major platform for cancer treatment. ACT involves using genetically engineered human lymphocytes, and is increasingly being investigated in patients with hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Currently, there are three well-developed ACT techniques: autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy, T-cell receptor (TCR)-engineered T-cell therapy (TCR-T), and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T). Manufacturing TIL products can be logistically challenging, but TCR-T therapy is gaining interest as CAR-T trials have so far failed to elicit satisfactory responses in the treatment of solid cancers. Many believe that TCRs may be better suited for the treatment of solid cancers. Recent clinical trials have shown promising results for the safety and efficacy of TCR-T therapies in treating both hematological and solid tumors.

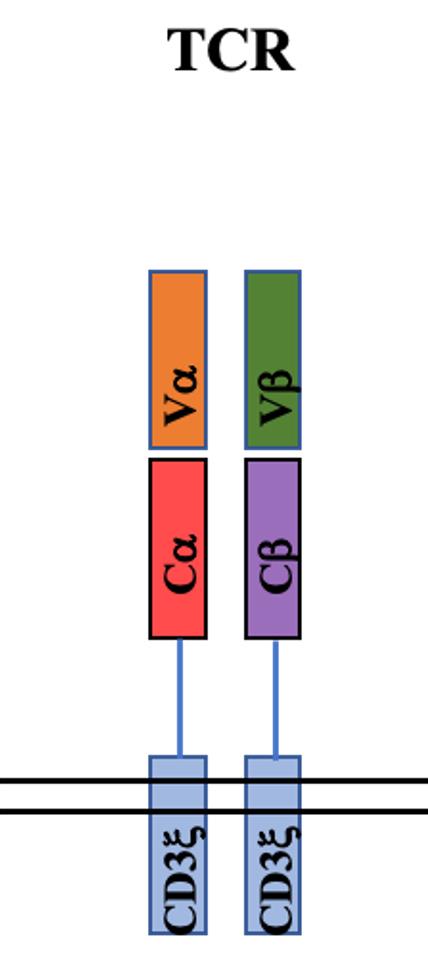

TCR-T is an adoptive cell therapy that employs genetically modified T cells to target specific tumor antigens and elicit potent antitumor responses. In TCR-T therapy, engineered T cells are modified to express a full TCR complex, consisting of TCR α- and β-chains, and rely on clusters of CD3 chains for signaling upon antigen recognition. With the expression of the complete TCR complex, engineered TCR-T cells can recognize polypeptide fragments expressed both within the tumor cell and at the cell surface, allowing for a broader range of target antigens. In clinical trials, TCR-T therapy has successfully targeted various tumor antigens, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) for colorectal cancer, glycoprotein gp100 (PMEL) and melanoma antigen recognized by T-cells 1 (MART-1) for melanoma, melanoma-associated antigen 3 (MAGE-A3) for melanoma and multiple myeloma, and New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1) for melanoma and synovial cell sarcoma. In particularly, an affinity-enhanced NY-ESO-1 TCR demonstrated impressive clinical response rates of 45-55% in metastatic melanoma patients and 50-61% in metastatic synovial sarcoma patients. The same NY-ESO-1 TCR achieved an 80% clinical response rate in multiple myeloma patients without apparent side effects, including a 70% complete response rate with a median progression-free survival of 19 months. Recently, a phase 1 trial of TCR-T targeting HPV-16 E7 in metastatic HPV-associated epithelial cancers demonstrated a 50% clinical response rate (6/12 patients), including 4/8 patients who were refractory to PD-1 blockade.

Despite the promising clinical outcomes, TCR-T faces a significant challenge of off-target toxicity due to mispairing of introduced and endogenous TCR α/β chains. This mispairing can create novel TCRs with unknown specificities that might recognize healthy tissues. Since the TCR α/β chains mainly interact through their constant regions, which are shared by both the endogenous and introduced TCRs, strategies to prevent or reduce TCR mispairing are necessary to improve the safety and efficacy of TCR-T. There are two primary consequences of TCR mispairing. First, it results in reduced expression of the engineered TCR on the cell surface because many of the introduced TCR α/β chains will form non-functional heterodimers with the endogenous TCR α/β chains. Additionally, these mispaired TCRs will compete with the engineered TCR for binding to the CD3 complex, which is essential for TCR signaling. Second, it generates novel TCRs that have escaped thymic selection and could recognize self-antigens, leading to potential autoimmunity. Despite the theoretical risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) due to TCR mispairing, no cases of GVHD have been reported in human TCR-T clinical trials so far, even in the early trials that used unmodified human TCRs. Nevertheless, most of the current TCR-T applications employ at least one strategy to minimize TCR mispairing and enhance TCR-T safety and efficacy.

Fig.1 Structure of TCR

Fig.1 Structure of TCR

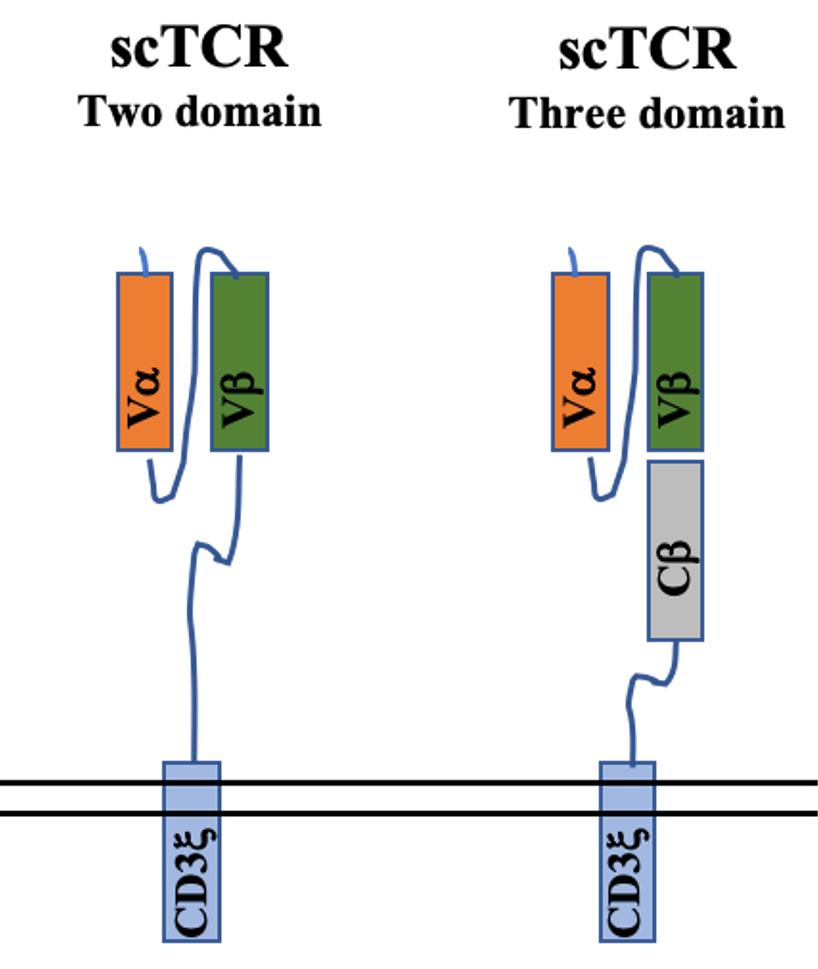

To address the issues related to the pairing of endogenous TCRs, researchers have developed single-chain TCR (scTCR) chimeras. ScTCR results in a single polypeptide that is designed to prevent mispairing by covalently linking the Vα and Vβ domains with a polylinker (PLK), which leads to steric hindrance. The fusion of CD3ζ onto the Cβ chain within the scTCR provides T cell activation signaling upon antigen encounter.

Fig.2 Structure of scTCR

Fig.2 Structure of scTCR

Several groups have created three-domain scTCRs, which consist of Vα/Vβ regions connected by a short peptide linker and attached to a Cβ domain. These scTCRs mimic the antigen recognition properties of a TCR α/β heterodimer. To enable signal transduction, three-domain scTCRs are typically fused to CD3ζ.

To evaluate the functional avidity of scTCRs, a study examined nine three-domain single-chain T cell receptors (scTCRs) that were fused to CD3ζ with or without additional stimulatory domains CD28 and Lck. The results showed that the presence of both CD28 and Lck enhanced the scTCR function, but none of the scTCR constructs matched the performance of native TCRs. ScTCR constructs utilizing CD3ζ transmembrane and signaling domains can function independently of the CD3 complex. This theoretically allows for higher surface expression to be achieved with scTCRs than with native TCRs, as scTCRs are not limited by the abundance of CD3 components. The ability of scTCRs to function without CD3 may have advantages in situations where the expression of native TCRs needs to be preserved.

However, scTCRs rely on signaling mechanisms that differ from those of native TCRs, which depend on CD3. This difference may partly account for the lower functional avidity of scTCRs. To generate scTCRs that preserve CD3-dependence, another research group designed a system where three-domain TCRs without CD3ζ conjugation, were co-expressed with a Cα domain. In this way, the three-domain scTCR dimerizes with the coexpressed Cα domain, presenting itself on the cell surface in a four-domain structure similar to that of a native TCR heterodimer. Interestingly, these scTCR/Cα constructs have comparable functional avidities to native TCRs. However, three-domain scTCRs still mispair with endogenous TCR α chains to some extent due to the presence of the Cβ domain. To create an scTCR system that completely prevents mispairing, the group developed two-domain scTCRs that use stabilizing Vα/Vβ mutations to eliminate the need for a Cβ domain. To mediate signaling, two-domain scTCRs are conjugated to intracellular signaling domains such as CD3ζ and CD28. Interestingly, two-domain scTCRs that contain CD3ζ/CD28 are essentially chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that use a Vα/Vβ domain for antigen recognition. Therefore, two-domain scTCRs exhibit characteristics typical of CARs such as CD3-independent signaling and reduced sensitivity to low antigen density.

Recent studies have explored the use of virus- or cancer-specific T-cell receptors (TCRs) to enhance the T-cell response of patients. Ongoing studies are also attempting to optimize this approach. In a related strategy to provide tumor-reactive T cells, transduced T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that contain a single-chain TCR fused to intracellular T-cell signaling domains (such as CD28, CD3ζ, and Lck) have entered clinical testing. Building on these approaches, several labs have explored the use of single-chain, three-domain TCRs (VαVβCβ) that can trigger proximal signaling through attached intracellular signaling domains. Theoretically, these TCR fusions have several benefits. A single gene product could recognize pepMHC antigens on target cells and activate the effector functions associated with T cells, independent of endogenous CD3 molecules. However, the three-domain strategy has been limited in some cases because the TCR surface expression is not sufficient for the recognition of low amounts of antigen.

Another potential benefit of the scTCR fusion approach is that it maintains the expression of endogenous TCR/CD3 complexes on transduced T cells at the same level as on their parental cells. In a study of T cells that expressing two transgenic TCRs, it was found that one TCR could overcome tolerance induced by the other TCR through its signaling. It has also been demonstrated that activation of T cells through the endogenous TCR can enhance the persistence of transduced T cells, thereby improving their efficacy against the target antigen of the transduced TCR. Thus, the capacity of scTCR fusions to prevent mispairing could maintain efficient signaling through the endogenous TCR and prevent the formation of heterodimers with unknown specificity, while allowing the introduced scTCR fusion to mediate redirected activity against tumor or viral epitopes at the same time. Since the first report of redirected T cell specificity through TCR transfer in 1986, tremendous progress has been made in TCR T therapies and their applications. Advances in technologies and strategies have improved the efficiency and affordability of TCR discovery efforts. These early results give reason for optimism in the continued development of TCR T therapies for cancer.

References

For any technical issues or product/service related questions, please leave your information below. Our team will contact you soon.

All products and services are For Research Use Only and CANNOT be used in the treatment or diagnosis of disease.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

The latest newsletter to introduce the latest breaking information, our site updates, field and other scientific news, important events, and insights from industry leaders

LEARN MORE NEWSLETTER NEW SOLUTION

NEW SOLUTION

CellRapeutics™ In Vivo Cell Engineering: One-stop in vivo T/B/NK cell and macrophage engineering services covering vectors construction to function verification.

LEARN MORE SOLUTION NOVEL TECHNOLOGY

NOVEL TECHNOLOGY

Silence™ CAR-T Cell: A novel platform to enhance CAR-T cell immunotherapy by combining RNAi technology to suppress genes that may impede CAR functionality.

LEARN MORE NOVEL TECHNOLOGY NEW SOLUTION

NEW SOLUTION

Canine CAR-T Therapy Development: From early target discovery, CAR design and construction, cell culture, and transfection, to in vitro and in vivo function validation.

LEARN MORE SOLUTION