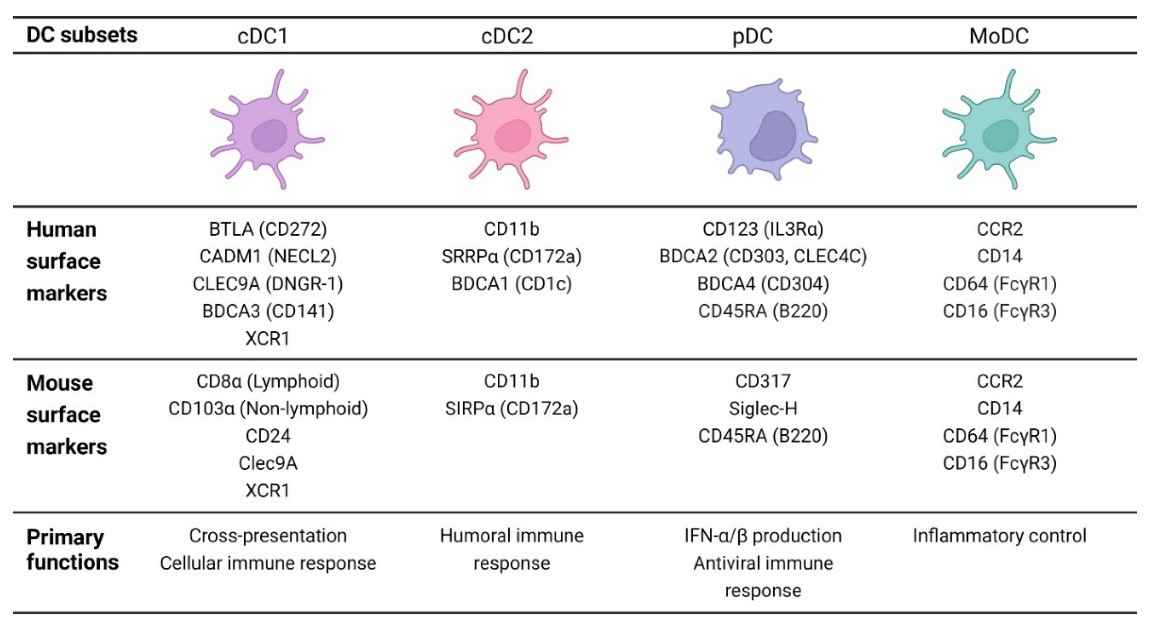

Dendritic cells (DCs) were first discovered in 1973 and are mainly involved in antigen-presenting processing, immune surveillance, and phagocytosis. Originating from the bone marrow of CD34+ stem cells, DCs are a sparsely distributed group of heterogeneous specialized Ag-presenting cells (APCs). It takes professional antigen-presenting cells to link innate and adaptive immunity. DCs are divided into four major subsets, namely conventional DCs (cDCs), plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs), and Langerhans cells (LCs) (Figure 1).

Fig.1 Different subsets of dendritic cells. (Burbage, 2020)

Fig.1 Different subsets of dendritic cells. (Burbage, 2020)

cDC1s and cDC2s are derived from common DC precursors. cDC1s present antigens to CD8+ T cells via MHCI, whereas cDC2s present antigens to CD4+ T cells via MHCII. cDC1 plays a key role in inducing antigen-specific immune responses against intracellular pathogens and promoting CD8+ CTL and Th1 responses. cDC2 are the major DC population in blood and lymphoid tissues, presenting antigens to naive CD4+ T cells mainly through the MHCII pathway. cDC2s can induce a variety of effector T cells (Th1 cells, Th2 cells, Th17 cells, Treg cells, and TFH cells), and can also activate CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, cDC2 is essential for the induction of Th2 responses, thus playing a dominant role in host defense against extracellular pathogens. pDCs typically respond by producing high levels of type I interferon as well as other inflammatory cytokines (IL6 and TNFα). Only bone marrow-derived pDCs have been found to process and display antigens. In addition to activation status, the role of pDCs in cancer may also depend on their degree of bone marrow origin. moDCs are commonly differentiated from mouse and human Ly6C+ or CD14hi monocytes, respectively, under inflammatory conditions. moDCs have not been shown to transport antigens to lymph nodes or activate T cells. The role of moDC in inducing de novo T cell responses is currently unclear. However, under inflammatory conditions, the recruitment of moDC is enhanced, which leads to the induction of "TipDC" (tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and NOS2-producing inflammatory dendritic cells) from moDC. They appear to be essential for maintaining immune responses under certain inflammatory conditions. The developmental origin of LCs is embryonic macrophage lineage precursors, and LCs can arise from circulating monocytes under inflammatory conditions. During inflammation, activated LCs elongate their dendrites at tight junctions to externally capture antigens. Then, upon stimulation by locally produced inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, LCs lose their connection with surrounding epithelial cells and migrate to draining lymph nodes. Under physiological conditions, LCs may play a role in maintaining skin immune tolerance and preventing harmful immune activation.

DCs are distributed everywhere in the human body, mainly in an immature state. Immature DCs (iDCs) can transform into mature DCs (mDCs) after ingesting antigens or being stimulated by immune inflammation. iDCs have a strong phagocytic ability but a weak antigen presentation ability, which means that their ability to activate T cells is also poor. The phagocytic ability of mDCs is weakened, but the ability to present antigen is strong.

DCs are immature in the resting state and acquire antigen in situ through a complex and tightly controlled activation process. Activation is characterized by the upregulation of chemokine receptors (e.g., CCR7), adhesion molecules, co-stimulatory molecules (CD54, CD80, and CD86), immunoproteasomes, and MHC class I and MHC class II molecules, all of which migrate to lymphoid tissue for optimal activation of the immune response. DC maturation is characterized by reduced phagocytic capacity, enhanced antigen processing and presentation, improved migration to lymphoid tissues, and an increased ability to stimulate B and T cells. Maturation is induced by microbial products that trigger activation of pattern recognition receptors (such as TLRs) or intracellular sensors (such as RIG-I35 or the inflammasome) or by inflammatory molecules (TNFα, IL-1, IL-6, and IFNα) produced by immune system cells or damaged tissue.

After the uptake of antigens (Ags) by DCs, Ags can be processed and presented by MHC-I or MHC-II molecules. MHCI is expressed in most cells, antigens are presented to CD8+ T cells through MHC I, and Ags are processed into peptides through the endogenous pathway; MHC-II is expressed only on Ag-presenting cells (APCs) and presents Ags to CD4+ T cells to participate in extrinsic pathway processing into peptides. In addition, DCs can also process antigens through two cross-presentation pathways: the cytosolic pathway and the vacuolar pathway. DCs can recognize Ags through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and then mature in response. Mature DCs require physical contact with T cells to present Ags for T cell activation. Soluble antigens can be readily delivered to T cells by lymphoid tissue-resident DCs. However, insoluble antigen delivery to T cells from peripheral tissues requires the migration of DCs to lymphoid tissues. In this process, DCs need to use Fc receptors (Fcγ receptor type I or CD64 and Fcγ receptor type II or CD32), integrins (αvβ3 or αvβ5), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs, including mannose receptors and DEC205), apoptotic cell death receptors, and scavenger receptors. After maturation, DCs migrate to secondary lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes (where they capture antigens from the skin and solid organs), the spleen (where they capture antigens from blood), or lymph nodes (where they capture antigens from the intestinal lumen), where they interact with T cells and B cells.

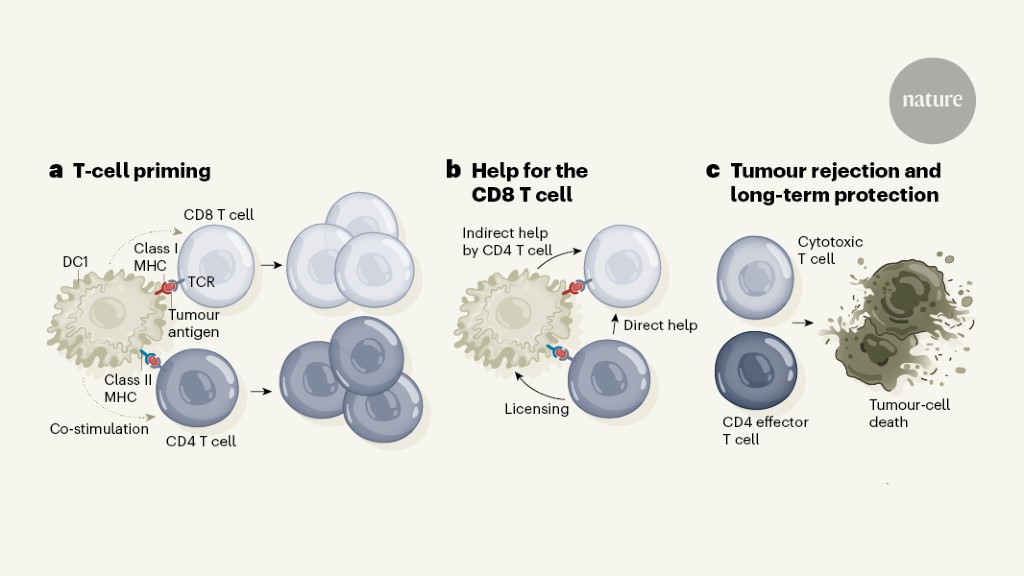

Proper localization of DCs is tightly regulated by a variety of chemotactic and non-chemotactic signals, including bacterial products, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), complement proteins, lipids, and chemokines. These signals form a complex regulatory network that is regulated at multiple levels by different strategies for different pathological conditions and will lead to the discovery of new molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. DCs in peripheral tissues migrate to the draining lymph nodes where they present antigens to naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, resulting in the induction of effector T cells. In the case of intracellular antigens, DCs process them and present antigen peptides through the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pathway. This leads to the induction of CD8+ CTLs. In the case of extracellular antigens, DCs usually process them and present antigen peptides through the MHC class II pathway that preferentially activates CD4+ T cells (Figure 2).

Fig.2 The process of DCs helps T cells to target tumors. (Verheye, 2022)

Fig.2 The process of DCs helps T cells to target tumors. (Verheye, 2022)

DCs have long been a focus of cancer immunotherapy due to their role in inducing protective adaptive immunity, as critical regulators of the immunotherapy of tumors. DCs have a unique ability to transport tumor antigen to the draining lymph nodes to initiate T cell activation, a process that is required for T cell-dependent immunity and response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB).

The lung cancer therapeutic landscape has experienced dramatic changes, including DC-based immunotherapy, oncogene-targeted small molecules and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Since the early 2000s, some clinical trials with DCs immunotherapy have been conducted. According to the available clinical evidence, DC-based immunotherapy is safe and well-tolerated. DCs can elicit antitumor immune responses in many patients with lung cancer, mainly in the metastatic setting where a predominant immunosuppressive climate. Combining DC-based immunotherapy with other anticancer therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and checkpoint inhibition, may improve effectiveness. Basic experimental research has discovered some new epitopes of antigens, which can induce immune responses in lung cancer cells, but clinical trials to prove effectiveness are still underway. Additional challenges for the future of DCs therapy are determining the adequate dose, frequency, and duration of treatment, improving the choice of target antigens, and finding biomarkers to select potential responders upfront. Identifying the most synergistic combinatorial regimen can hold the real key to long term disease control and survival in this lethal disease.

DC-based strategies aiming to elicit effective anti-MM immune responses have evolved tremendously over the past few decades. The naked idiotypic protein to immunize MM patients resulted in unsatisfactory immune responses. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are suitable natural adjuvants and are considered vaccination therapies for cancer immunotherapy. Up until now, DC-based therapeutic strategies in MM have been tried many times in a clinical setting. DC-based vaccines evolved from the first-generation to the second-generation and the rising next generation. In general, first- and second-generation DC vaccines are proven to be safe and feasible in MM patients, independent of the patient's clinical stage and the DC vaccination strategy. Although DC-based therapy initially provides antitumor immunity, long-term clinical responses are limited. Mild febrile reactions occurred in some patients. In addition, DC-based therapy combined with immunomodulators and checkpoint inhibitors is a good strategy to improve the therapeutic efficacy of MM patients. To eradicate minimal residual disease and prevent relapse in myeloma patients, novel, improved DC-based approaches and alternative DC sources should be considered.

DC-based immunotherapy has the potential to bring about demonstrable clinical responses in patients with AML, particularly in the post-remission setting of AML. DCs treatment in AML can produce durable remissions and prevent or delay relapse in some high-risk patients. Existing studies have shown that DC-vaccinated patients who fail to mount an immune response have poorer clinical outcomes compared with those with an immune response, suggesting that eliciting DC-based (anti-leukemia) immunity is required to obtain a clinical response. However, there are also a considerable number of patients who do not mount a clinical response despite the presence of DC-induced immune changes. Therefore, it is important that DCs currently used for immunotherapy evoke clinically beneficial immune responses.

Combining DC therapy with immune checkpoint targeting strategies is another avenue to unlocking the full therapeutic potential of DC vaccines for AML. Combining DC vaccination with conventional therapies can unexpectedly potentiate the response to subsequent treatment, an observation that has also been made in the solid tumor vaccine field. Several randomized clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate the effectiveness of combination therapy.

DC-based vaccines are considered an alternative therapeutic approach to treating EC. DCs are a focus for orchestrating the immune system in the fight against cancer. DC-based therapy has resulted in new strategies, including cancer vaccines, combination therapy, and adoptive cellular therapy. Especially immunotherapy is currently becoming an unprecedented bench-to-bedside success, but the overall response rate to the current immunotherapy in patients with GI cancers is pretty low.

DC-based vaccines are considered an alternative therapeutic approach to treat EC. The combination therapy of pemetrexed with DCs as a third-line treatment was effective as well as well tolerated in advanced EC patients. Immunotherapy using a combination of DCs and cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells showed promising clinical outcomes for treating EC, and it has the advantages of safety, prolonging survival time, enhancing immune response, and improving therapeutic efficacy.

In the peripheral blood, patients with GC were identified to have a substantially higher percentage of peripheral pDCs and CD1c+ myeloid DCs (mDC2). Moreover, blood pDCs were a prognostic factor in GC patients and played a pivotal role in the progression of GC. Cord blood-derived DCs and CIK were clinically exploited for the treatment of GC. Patients with advanced GC were treated with CB-DC-CIK plus chemotherapy, and there were no serious adverse effects were observed in patients with GC.

An alpha-fetoprotein-derived peptide-loaded DC vaccine could promote an AFP-specific anti-tumor immune response in patients with HCC, mainly inducing CD8+ T-cell responses. DC-CIK immunotherapy is safe and effective in the treatment of HCC patients. The co-culture of DCs and CIK cells could inhibit the proliferation and migration of HCC cells by the regulation of PCNA and BAX, and DC-CIKs significantly enhanced the apoptosis ratio by increasing caspase-3 protein expression and reducing PCNA expression against liver cancer stem cells. Moreover, the efficacy of combination therapy of DC-CIKs pretreated with pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) against HCC was further improved in clinical investigation. Thus, blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway in DC-CIK cells prior to the infusion is a promising treatment strategy against HCC.

DC-CIK immunotherapy has been widely used in treating PC patients. Both chemotherapy drugs and miRNA-depleted tumor-derived exosomes could enhance the efficacy of DC-CIK immunotherapy. The combination therapy showed advantages over chemotherapy alone. The combination of DC-CIK immunotherapy and chemotherapy enhanced the PC patients' survival time, being an effective treatment strategy. The miRNA-depleted exosome could be a promising agonist for stimulating DC/CIKs against PC.

Several meta-analyses of clinical trials with CRC patients all showed that the combination of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy and chemotherapy prolonged the survival time, enhanced immune responses, and alleviated chemotherapy-mediated side effects.

By modifying their genes, dendritic cells can be optimized to recognize and attack cancer cells more efficiently. These genetically engineered dendritic cells are then reintroduced into the body, where they can trigger an immune response against cancer. Studies have shown promising results in early phase clinical trials for various types of cancer, including melanoma and prostate cancer. Genetically engineered dendritic cells have the potential to revolutionize cancer treatment by providing an effective and personalized approach with minimal side effects, showing great promise for the future of cancer treatment.

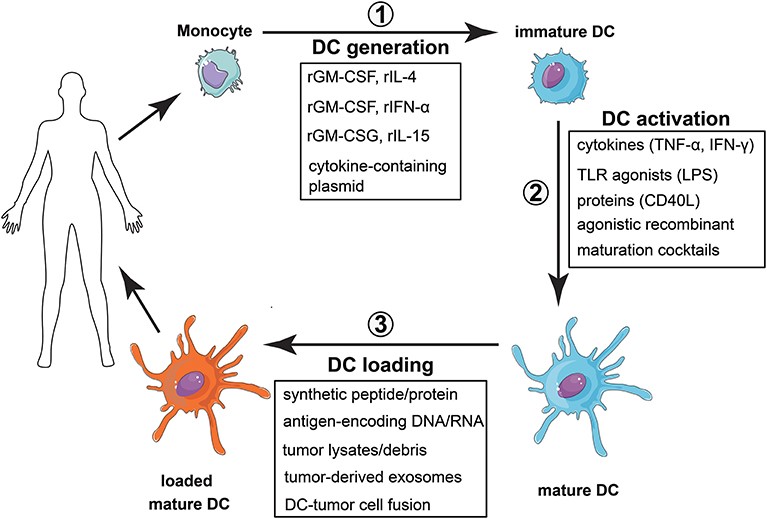

DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells that bridge innate and adaptive immune responses. After antigen capture, DCs leave peripheral tissues, enter the lymphatic system, and migrate to lymph nodes, where they initiate adaptive responses by presenting antigens to specific T cells. DCs represent a key factor in the activation of immunity and tolerance. DC-based antitumor vaccines are being tested in clinical trials on solid tumors and hematological malignancies, seeking to improve therapeutic responsiveness by modulating DC migration, seeking new therapeutic strategies, and bringing hope for tumor therapy (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Vaccination strategy with monocyte-derived dendritic cells. (Patente, 2019)

Fig. 3 Vaccination strategy with monocyte-derived dendritic cells. (Patente, 2019)

The over 200 clinical trials testing DC vaccines have shown that DC are safe vaccines, highly immunogenic, and periodically able to activate an antitumor immune response capable of inducing a durable, objective tumor regression and clinical response in a previously treated, late-stage cancer patient. That is why DC will continue to be tested ashave shown that DC vaccines are safe, highly immunogenic, and periodically able to activate an antitumor immune response capable of inducing a durable, objective tumor regression and clinical response in a previously treated late-stage cancer patient. That is why DC will continue to be tested as a cancer vaccine in new stages of cancer, new tumor histologies, and new combinations. DCs are specialized APCs that are fundamental to the initiation of immunity and tolerance. DCs act as 'sentinels' that protect our body from potential pathogens and induce tolerance responses to harmless antigens. Currently, it is evoking a renaissance in the cancer immunotherapy field.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting dendritic cells represent a cutting-edge therapeutic approach with significant potential in immunotherapy, particularly in the treatment of various cancers and autoimmune diseases. Dendritic cells, as key regulators of the immune system, play a pivotal role in initiating and modulating immune responses. By developing monoclonal antibodies that specifically target these cells, researchers aim to harness and manipulate the immune system's natural mechanisms to fight disease. This strategy not only opens avenues for more precise and targeted interventions but also offers the possibility of reducing side effects associated with broader immunosuppressive therapies. As such, the exploration of dendritic cell-targeted monoclonal antibodies is a promising frontier in medical research, offering hope for more effective and personalized treatments.

References

For any technical issues or product/service related questions, please leave your information below. Our team will contact you soon.

All products and services are For Research Use Only and CANNOT be used in the treatment or diagnosis of disease.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

The latest newsletter to introduce the latest breaking information, our site updates, field and other scientific news, important events, and insights from industry leaders

LEARN MORE NEWSLETTER NEW SOLUTION

NEW SOLUTION

CellRapeutics™ In Vivo Cell Engineering: One-stop in vivo T/B/NK cell and macrophage engineering services covering vectors construction to function verification.

LEARN MORE SOLUTION NOVEL TECHNOLOGY

NOVEL TECHNOLOGY

Silence™ CAR-T Cell: A novel platform to enhance CAR-T cell immunotherapy by combining RNAi technology to suppress genes that may impede CAR functionality.

LEARN MORE NOVEL TECHNOLOGY NEW SOLUTION

NEW SOLUTION

Canine CAR-T Therapy Development: From early target discovery, CAR design and construction, cell culture, and transfection, to in vitro and in vivo function validation.

LEARN MORE SOLUTION