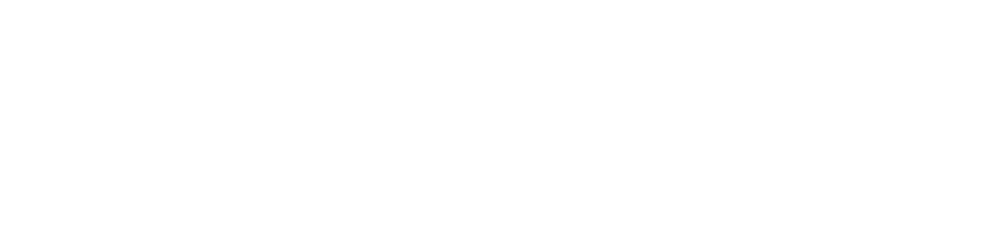

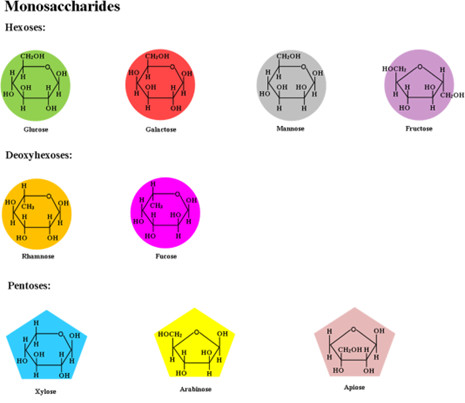

Monosaccharides, the simplest carbohydrate units, exhibit distinct structural and functional characteristics that underpin their biological roles. Their basic chemical formula follows the general pattern CnH2nOn, with n=3−7, representing trioses to heptoses. Common hexoses like glucose, fructose, and galactose (C6H12O6) differ in carbonyl group positioning (aldehyde in aldoses, ketone in ketoses) and hydroxyl group stereochemistry. For example, glucose is an aldose with a six-membered pyranose ring formed through cyclization, while fructose adopts a five-membered furanose ring due to its ketose nature. In aqueous solutions, these sugars predominantly exist in cyclic forms (>99%) due to their thermodynamic stability, with linear and ring structures dynamically interconverting via mutarotation.

Fig.1 Chemical structure of monosaccharides.1,3

Fig.1 Chemical structure of monosaccharides.1,3

Conformational Properties of Monosaccharides

At Creative Biolabs, we recognize that understanding monosaccharide conformations is essential for advancing glycoscience and therapeutic research. The spatial arrangement of sugar rings dictates their stability and biological interactions, influencing everything from enzyme recognition to glycoprotein functionality. We offer advanced analytical solutions, including lectin microarray and MS, to characterize glycan structures with high precision. Techniques such as LC-ESI-MS, MALDI-TOF MS, and HPLC enable precise analysis of monosaccharide conformations in complex biological systems. Coupled with NMR and FTIR, our platform supports comprehensive glycoprofiling. Whether through flow cytometry or TLC, we provide tailored solutions to explore the structural complexity of carbohydrates.

|

Monosaccharide Type

|

Conformational Forms

|

Description

|

Stability & Biological Relevance

|

|

Pyranose (Six-Membered Ring)

|

Chair (C1 or C4 form)

|

- Most stable form due to minimal steric hindrance.

- Substituents adopt axial (A) or equatorial (E) positions.

|

β-D-glucose adopts a chair conformation with all bulky groups in equatorial positions, making it the most stable form.

|

|

Boat (B form)

|

- Higher steric hindrance due to 1,3-diaxial interactions.

- Typically an intermediate during ring conformational changes.

|

Rarely observed in solution, usually as a transition state in mutarotation.

|

|

Furanose (Five-Membered Ring)

|

Envelope (E form)

|

- One ring atom (e.g., C2 or C3) deviates from the planar structure.

|

Found in RNA and DNA (ribose and deoxyribose adopt puckered forms for structural flexibility).

|

|

Twist (T form)

|

- Two adjacent ring atoms move out of the plane, creating a twisted structure.

|

Provides conformational flexibility in sugar-binding interactions (e.g., enzyme-substrate recognition).

|

Monosaccharides Cyclic and Linear Forms

Monosaccharides in aqueous solutions exist in an equilibrium between their cyclic and open-chain structures via reversible hemiacetal or hemiketal formation. Cyclic structures arise through intramolecular hemiacetal/hemiketal reactions. In aldoses like glucose, the aldehyde group at C1 reacts with the hydroxyl group on C5, forming a six-membered pyranose ring. In contrast, ketoses like fructose involve the ketone group at C2 reacting with the C5 hydroxyl to yield a five-membered furanose ring. This process generates an anomeric carbon (originally the carbonyl carbon), which determines the α (hydroxyl below the ring plane) or β (hydroxyl above) configuration. These anomers exhibit distinct optical rotations and biological activities, such as the differential recognition of α- and β-glucose by enzymes. The prevalence of five- and six-membered rings aligns with Bayer's strain theory, minimizing ring tension and maximizing stability. The proportion of each form depends on steric factors, solvent effects, and temperature:

-

High temperatures or polar solvents favor the open-chain form.

-

Acidic or basic conditions accelerate ring opening and closing.

-

Large substituents stabilize specific conformations due to steric effects.

Monosaccharide Disaccharide Polysaccharide Structure

Monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides differ fundamentally in complexity, solubility, and biological functions. Monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose) serve as immediate energy substrates and metabolic intermediates. Disaccharides like sucrose (glucose + fructose) and lactose (glucose + galactose) act as transportable energy forms, linked by α/β-glycosidic bonds. In contrast, polysaccharides—comprising hundreds to thousands of monosaccharide units—exhibit structural and storage roles. Starch (α-1,4 and α-1,6 linkages) stores energy in plants, while cellulose (β-1,4 linkages) provides rigidity to plant cell walls. Glycogen, a highly branched animal polysaccharide, enables rapid glucose mobilization in liver and muscle. Unlike monosaccharides and disaccharides, polysaccharides are typically insoluble, non-sweet, and require enzymatic hydrolysis for digestion, contributing to slower glucose release and sustained energy provision.

|

|

Monomer Count

|

Bond Type

|

Examples

|

Function

|

|

Monosaccharides

|

1

|

-

|

Glucose, Fructose, Galactose

|

Direct energy source, Metabolic intermediates

|

|

Disaccharides

|

2

|

α/β-glycosidic bond

|

Sucrose (Glucose + Fructose)

|

Transport form, Quick energy supply

|

|

Polysaccharides

|

>10

|

Glycosidic bonds (linear/branched)

|

Starch (α-1,4/α-1,6)

|

Energy storage (plants)

|

|

Cellulose (β-1,4)

|

Structural support (plant cell wall)

|

|

Glycogen (highly branched)

|

Energy storage (animal liver and muscles)

|

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Monosaccharide Structural Characterization

Monosaccharide structural elucidation requires a combination of sophisticated analytical methods to resolve their complex stereochemistry, anomeric configurations, and linkage patterns. Creative Biolabs offers a comprehensive suite of advanced glycan analysis technologies to facilitate glycan characterization at high resolution. Below are key techniques employed for in-depth structural analysis.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

-

Anomeric Configuration & Linkage Analysis:

NMR identifies α/β anomers via distinct chemical shifts of anomeric protons and inter-residue correlations in 2D experiments (e.g., HSQC, HMBC). For example, IdeS-cleaved mAb fragments analyzed by 2D ¹H-¹³C HSQC NMR revealed glycan populations in therapeutic antibodies.

-

Dynamic Conformational Studies:

Paramagnetic NMR probes (e.g., lanthanide tags) and stable isotope labeling (e.g., ¹³C-glucose) enable tracking of glycan conformational changes in solution, critical for understanding ganglioside interactions in neurodegenerative diseases.

Mass Spectrometry (MS) with Orthogonal Separation

-

Isobaric Discrimination:

Coupling MS with LC-ESI-MS, MALDI-TOF MS, or HPLC enables high-resolution separation of glycans, resolving isobaric structures such as glucose and galactose isomers.

-

Sequential Fragmentation:

GC-MS and Imaging Mass Spectrometry employ MS³/MS⁴ techniques to dissect complex oligosaccharides into diagnostic fragments, enabling precise linkage and branching analysis.

Lectin/Glycan-Modifying Enzyme Assays

-

Linkage-Specific Cleavage:

Exoglycosidases (e.g., β-galactosidase) selectively hydrolyze terminal monosaccharides, with HPAEC-PAD and RP-HPLC profiling confirming cleavage patterns. β-1,4-galactosidase treatment distinguishes lactose (galactose-β-1,4-glucose) from other disaccharides.

-

Lectin Affinity Chromatography:

Lectin Microarray and SPRi are powerful tools for profiling glycan structures, utilizing lectins like ConA (specific for α-mannose/glucose) to enrich glycans with specific motifs.

Chemical Derivatization & Methylation Analysis

-

Methylation-Acid Hydrolysis:

TLC and UHPLC/FLD/Q-TOF enable detailed analysis of methylated glycan derivatives. This technique has been instrumental in identifying linkage positions in wheat bran arabinoxylan, revealing β-1,4-xylose linkages.

-

FITDOG (Fluorophore-Assisted Cleavage):

Nonenzymatic cleavage of polysaccharides into oligosaccharides, combined with FTIR and LC-MS, provides structural insights into native polysaccharides such as galactomannan in oats.

Published Data

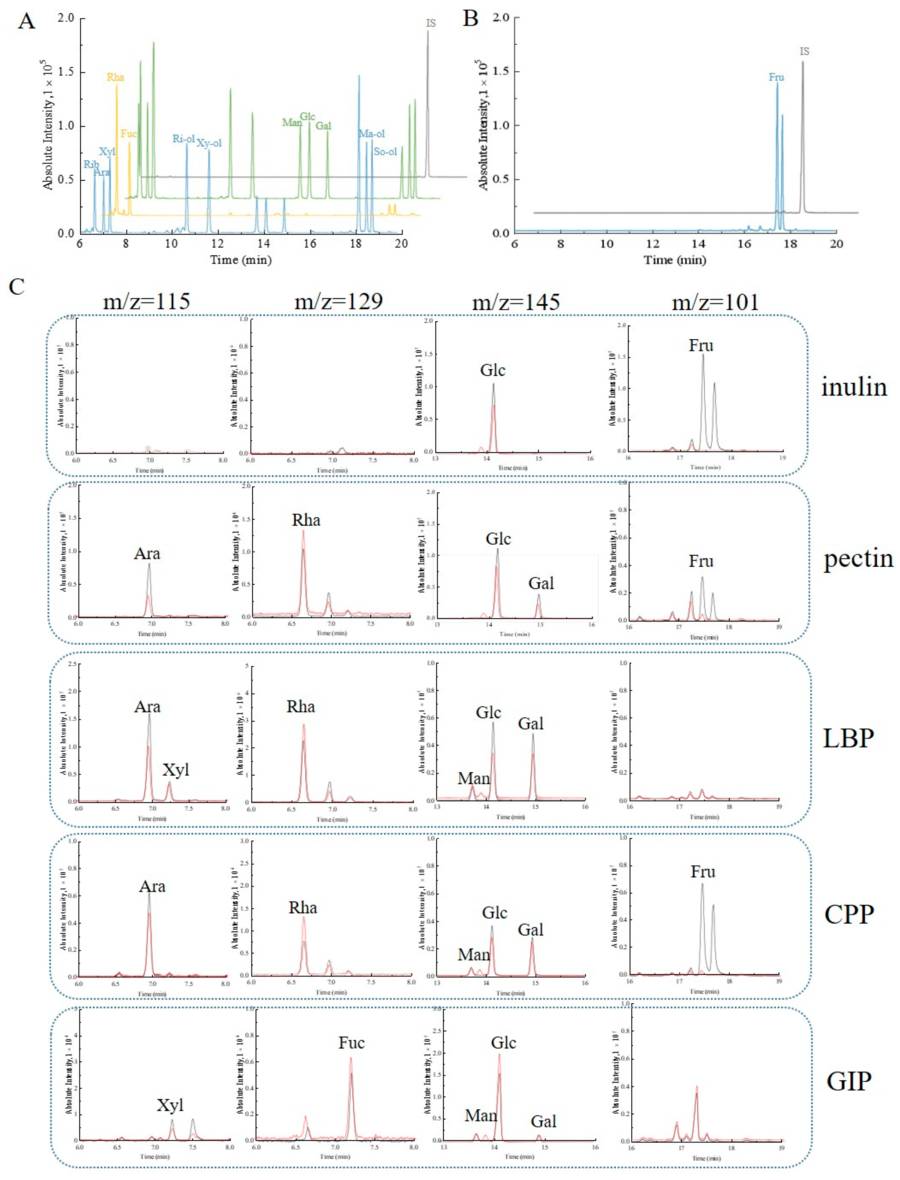

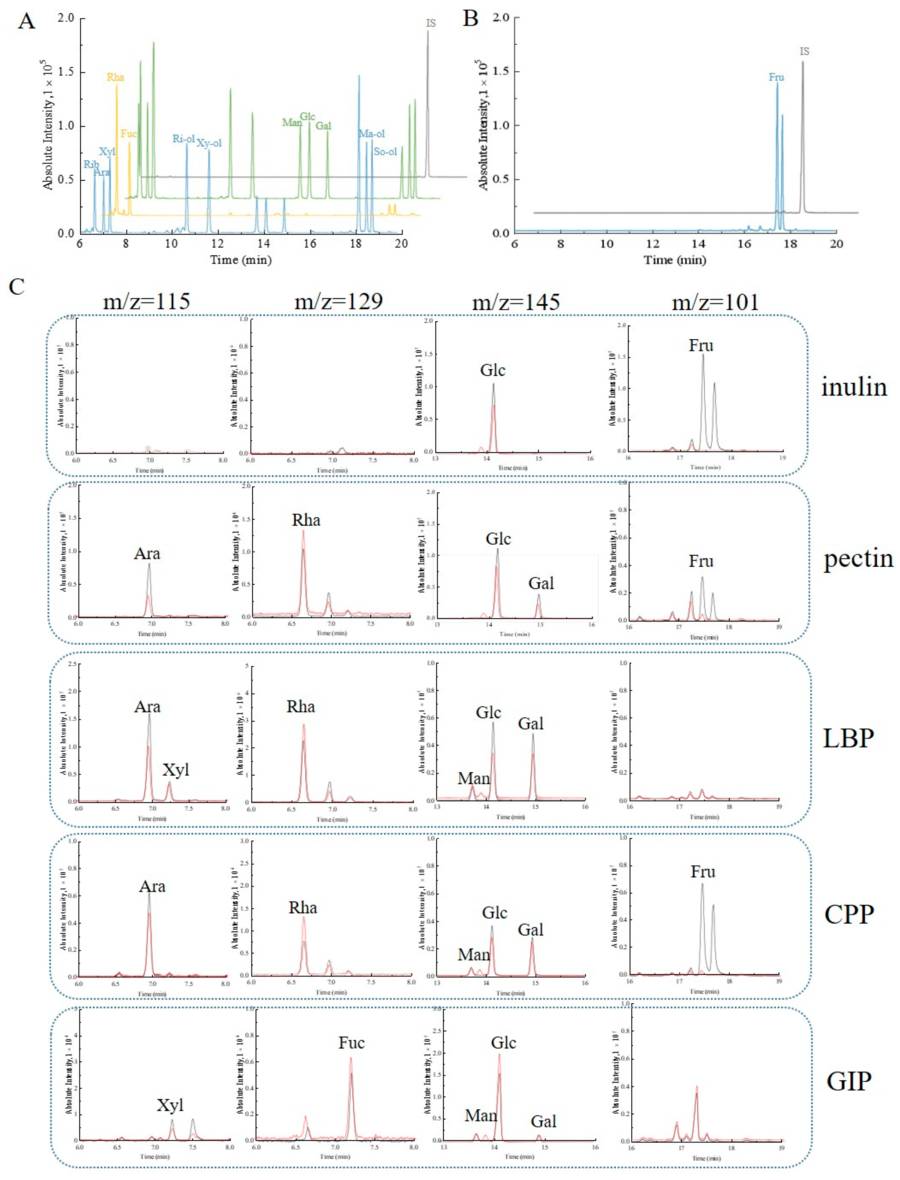

This study investigates the effects of hydrolysis conditions and detection methods on the monosaccharide composition analysis of natural polysaccharides. The monosaccharide composition is crucial for characterizing the structure and biological activity of polysaccharides, but different hydrolysis and detection methods may lead to varying results. The study employs multiple techniques, including colorimetric methods, high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), to analyze 16 monosaccharides (including aldoses, ketoses, alditols, amino sugars, and uronic acids) and compares one-step and two-step acid hydrolysis. The results indicate that GC-MS can effectively separate and detect aldoses, ketoses, and alditols, but not uronic acids or amino sugars. After two-step hydrolysis, fructose becomes undetectable in inulin and Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharides, while the content of uronic acids significantly increases. This highlights the high sensitivity and separation capability of GC-MS in monosaccharide composition analysis, but also emphasizes the significant impact of hydrolysis conditions on the results.

Fig.2 GC-MS analysis of monosaccharide composition in natural polysaccharides.2,3

Fig.2 GC-MS analysis of monosaccharide composition in natural polysaccharides.2,3

References

-

Navarro, Diego MDL, Jerubella J. Abelilla, and Hans H. Stein. "Structures and characteristics of carbohydrates in diets fed to pigs: a review." Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 10 (2019): 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0345-6

-

Zhao, Meijuan, et al. "Effects of hydrolysis condition and detection method on the monosaccharide composition analysis of polysaccharides from natural sources." Separations 11.1 (2023): 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations11010002

-

Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

Related Services

Resources

For Research Use Only.

Contact Us

Follow us on

Contact Us

Follow us on

Fig.1 Chemical structure of monosaccharides.1,3

Fig.1 Chemical structure of monosaccharides.1,3

Fig.2 GC-MS analysis of monosaccharide composition in natural polysaccharides.2,3

Fig.2 GC-MS analysis of monosaccharide composition in natural polysaccharides.2,3