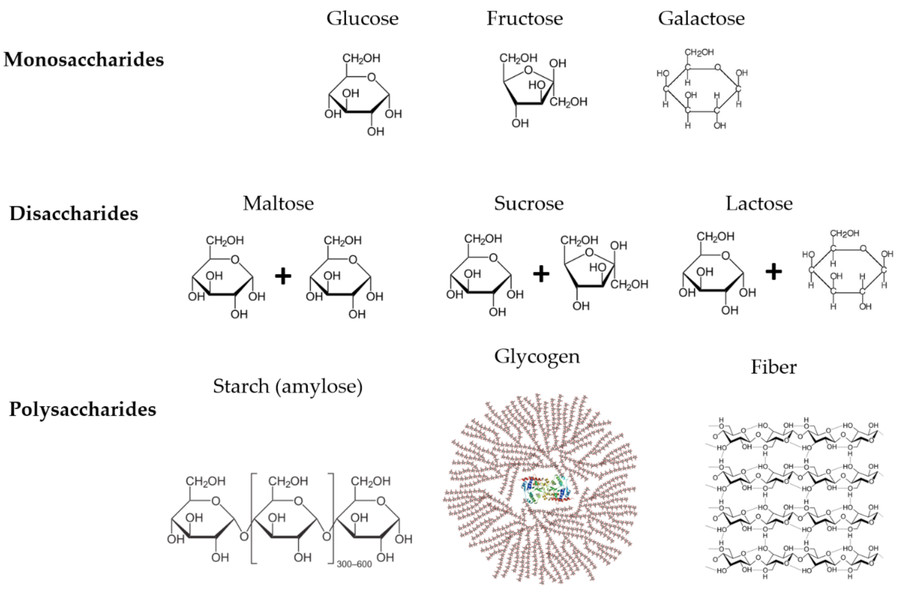

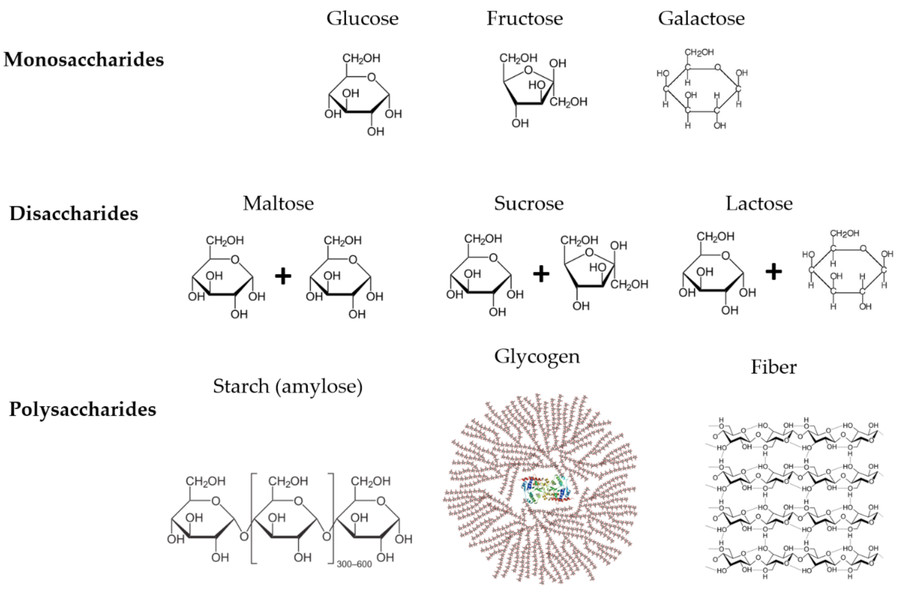

Carbohydrates, essential biomolecules in glycobiology and many biological processes, are classified into monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides based on their degree of polymerization. These structural differences define their biological functions, ranging from immediate energy supply to complex cellular interactions and storage mechanisms. Creative Biolabs is committed to deliver custom services spanning from glycan synthesis to carbohydrate analysis, and uses advanced glycan analysis techniques to understand the distinctions among monosaccharides, oligosaccharide, and polysaccharides, which is critical for advancing research in glycobiology, biochemistry, and related fields.

Fig.1 Examples of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Fig.1 Examples of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Structural Differences: Monosaccharide vs. Oligosaccharide vs. Polysaccharide

The classification of carbohydrates is rooted in their structural complexity. The simplest forms, monosaccharides, serve as the building blocks for larger oligosaccharides and polysaccharides. Each type exhibits distinct properties based on the number of sugar units and the way they are linked.

|

|

Number of Sugar Units

|

Example

|

Primary Function

|

|

Monosaccharides

|

1

|

Glucose, Fructose, Galactose

|

Immediate energy source

|

|

Oligosaccharides

|

2-10

|

Raffinose, Stachyose, Maltotriose

|

Prebiotic effects, cell recognition

|

|

Polysaccharides

|

>10

|

Starch, Glycogen, Cellulose

|

Energy storage, structural support

|

Glycosidic Bonds

Carbohydrates form through glycosidic bonds, which connect monosaccharide units via condensation reactions. These bonds vary in linkage position and stereochemistry, influencing digestibility and function.

|

Bond Type

|

Example

|

Digestibility

|

|

α-1,4-glycosidic bond

|

Found in starch (amylose) and maltose

|

Easily digested by amylase

|

|

α-1,6-glycosidic bond

|

Found in amylopectin and glycogen

|

Increases branching, enhancing enzymatic access

|

|

β-1,4-glycosidic bond

|

Found in cellulose

|

Indigestible by humans, fermentable by microbiota

|

|

β-1,3-glycosidic bond

|

Found in bacterial exopolysaccharides

|

Impacts biofilm formation

|

Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides are the fundamental carbohydrate units, consisting of a single sugar molecule. These small, water-soluble molecules function primarily as immediate energy sources. Their general chemical formula follows (CH₂O)n, where n typically ranges from 3 to 7.

-

Glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆): The central molecule in energy metabolism.

-

Fructose: Found in fruits and honey, sweeter than glucose.

-

Galactose: Essential for lactose formation in milk.

Structurally, monosaccharides exist in linear or cyclic (pyranose and furanose) forms, with cyclic structures being predominant in biological systems. Their functional groups, particularly the aldehyde (-CHO) or ketone (-C=O) groups, define whether they are aldoses or ketoses, influencing their reactivity.

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides contain 2 to 10 monosaccharide units, linked by glycosidic bonds. These short-chain carbohydrates participate in key biological processes, including prebiotic activity and cell-cell recognition. Oligosaccharide bonds exhibit diverse linkage types (α or β-glycosidic bonds), which impact digestibility and functionality.

-

Disaccharides (e.g., sucrose, lactose, maltose): The simplest oligosaccharides, formed via condensation reactions.

-

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and Galactooligosaccharides (GOS): Non-digestible compounds that selectively promote gut microbiota growth.

-

Glycoproteins and glycolipids: Oligosaccharide chains linked to proteins or lipids, playing roles in immune signaling and molecular recognition.

Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides are long carbohydrate chains, often exceeding thousands of sugar units, forming either linear or branched structures. Their functionality depends on the type of glycosidic bonds and degree of branching. Polysaccharides exhibit varied solubility and digestibility, influencing their nutritional and industrial applications.

-

Storage Polysaccharides:

-

Starch (plants): Composed of amylose (linear) and amylopectin (branched); major energy reserve in plants.

-

Glycogen (animals): Highly branched polymer, ensuring rapid glucose mobilization.

-

Structural Polysaccharides:

-

Cellulose (plants): Composed of β(1→4)-linked glucose units, indigestible by humans but essential for plant cell walls.

-

Chitin (arthropods, fungi): N-acetylglucosamine polymer forming exoskeletons and fungal cell walls.

Functional Implications

The polymerization of carbohydrates determines their biological significance and digestibility.

|

|

Energy Metabolism and Storage

|

Prebiotic and Gut Health Effects

|

Structural and Protective Roles

|

|

Monosaccharides

|

Rapidly enter glycolysis, generating ATP for cellular activities.

|

Not directly involved in prebiotic functions.

|

Play a minor role in structural integrity.

|

|

Oligosaccharides

|

Serve as intermediate energy sources (e.g., maltodextrins).

|

Act as prebiotics (FOS, GOS, XOS), selectively fermenting in the gut to stimulate Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli.

|

Contribute to cell recognition and glycosylation in biological systems.

|

|

Polysaccharides

|

Function as long-term energy reserves (e.g., glycogen, starch), mobilized when needed.

|

Fermentation of certain polysaccharides (resistant starch, pectin) produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), promoting gut health and metabolic regulation.

|

Provide mechanical support (cellulose in plants, chitin in arthropods); glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) help with tissue hydration and joint lubrication.

|

Applications in Research

Monosaccharide based Biomarkers: Precision in Diagnostic Tools

Monosaccharides serve as key indicators in metabolic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases. Their quantification provides critical insights into disease progression and treatment response.

-

Glucose is a primary biomarker for diabetes, routinely measured in blood tests.

-

Elevated fucose and mannose often indicate abnormal glycosylation, commonly associated with cancer progression. Thus, precision detection of these glycans' abnormal expression is essential for cancer stage identification.

-

Dysregulated ribose metabolism contributes to neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting diagnostic potential.

Creative Biolabs' advances in glycan profiling enhance precision medicine by integrating carbohydrate-based markers into disease monitoring and therapeutic decision-making.

Oligosaccharide Synthesis: Engineering Functional Glycans

Oligosaccharides play essential roles in biopharmaceuticals, glycomics, and gut microbiome research. Their controlled synthesis ensures functional specificity in biomedical applications.

-

Glycoprotein modification: Recombinant therapeutic proteins rely on precise oligosaccharide structures for enhanced stability and bioactivity. We offer custom oligosaccharide synthesis services, including but not limited to:

-

Prebiotic function: Selectively fermented fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and galactooligosaccharides (GOS) promote beneficial gut microbiota, particularly Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

-

Vaccine development: Bacterial oligosaccharides serve as immunogenic components in conjugate vaccines against pneumococcal and meningococcal infections. (Know more about carbohydrate chains in vaccines)

Polysaccharide Innovations: From Drug Delivery to Sustainable Materials

Polysaccharides offer unmatched biocompatibility and functional diversity, making them indispensable in pharmaceuticals, regenerative medicine, and biomaterials. Creative Biolabs provides high-quality polysaccharide synthesis and polysaccharide analysis services to develop next-generation biomaterials with improved functionality and sustainability.

-

Modified chitosan and alginate nanoparticles enable targeted drug delivery, enhancing bioavailability.

-

Polysaccharide-based hydrogels promote tissue regeneration while providing antimicrobial protection. (Know more about carbohydrate chains in tissue engineering)

-

Cellulose-derived bioplastics offer an alternative to petroleum-based plastics in eco-friendly packaging.

Optimizing Glycan Analysis with Advanced Profiling

For researchers in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and microbiome science, accurate saccharide profiling is fundamental to biotherapeutic quality control, microbiome-metabolome research and metabolic pathway analysis. At Creative Biolabs, we are well-experienced in ensuring precise glycosylation in monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and recombinant proteins, and provide you tailored glycoengineering services for therapeutic protein glycoengineering, therapeutic antibody glycoengineering and cell line glycoengineering. Equipped with advanced glycan analysis techniques such as HPLC, MS, and glycan microarrays for precise structural characterization, we are also proficient in delivering tests to analyze the role of glycans in metabolic pathway, facilitating research related to carbohydrate metabolism in disease models for targeted drug development.

Creative Biolabs specializes in glycan synthesis, analytical characterization, and saccharide engineering, providing researchers with the expertise needed to advance carbohydrate-based applications. Do not hesitate to contact us to for more information!

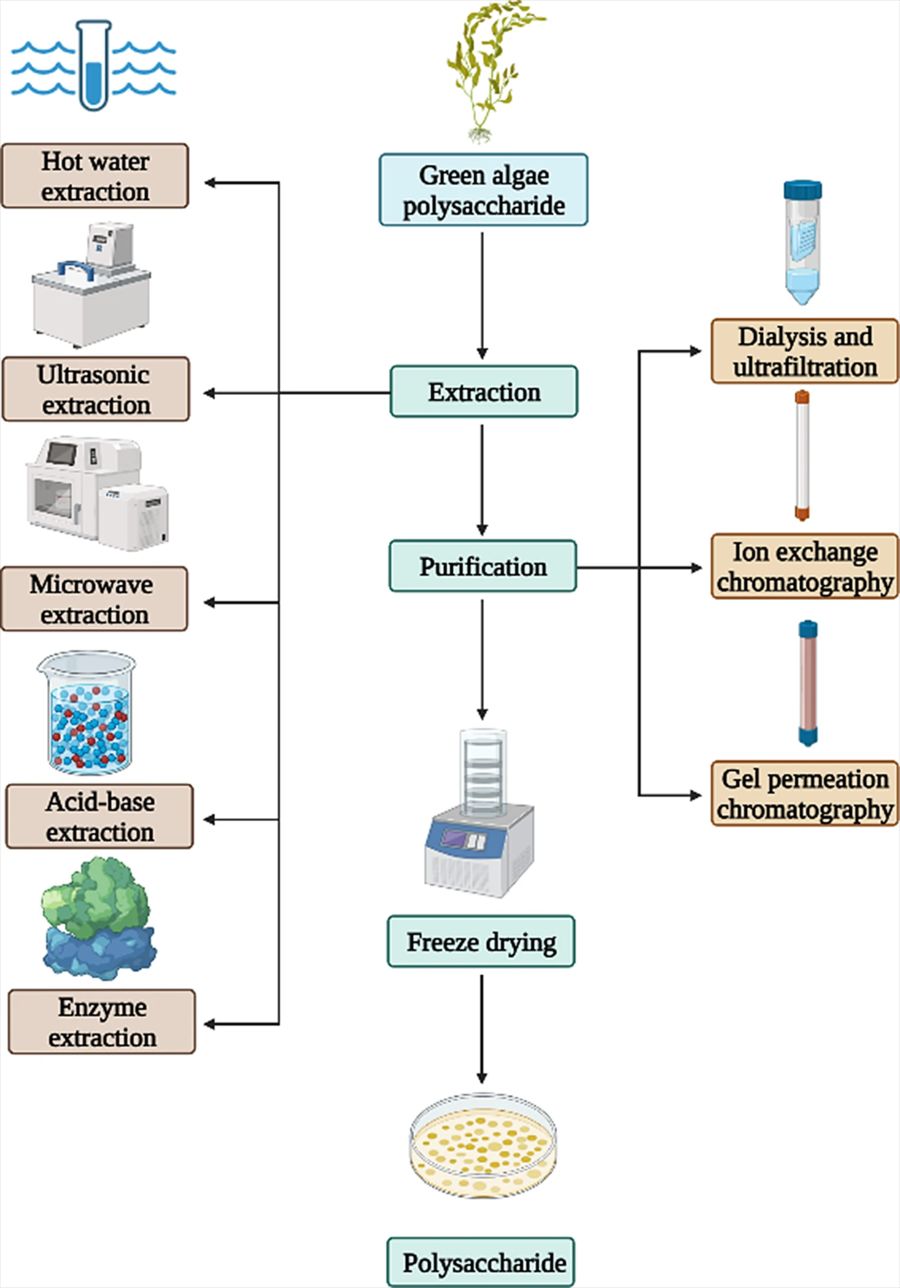

Published Data

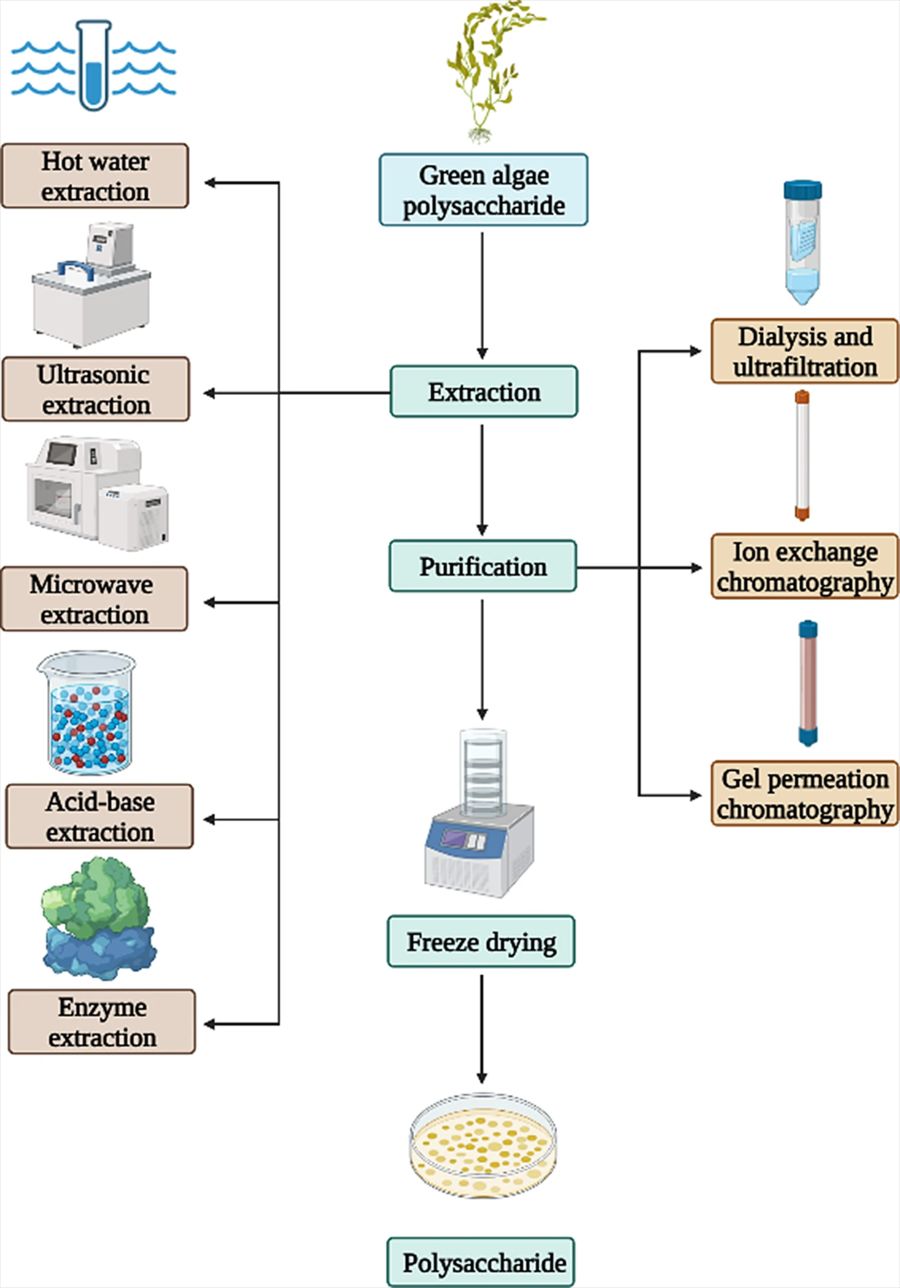

The biological activities and applications of green algae polysaccharides depend largely on their purity. Highly purified polysaccharides demonstrate superior antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anticoagulant, and antiviral properties, making them valuable in pharmaceuticals and health products. However, purification remains challenging due to low yields and high costs. Various extraction methods, including hot water, enzymatic, ultrasonic, microwave-assisted, and chemical approaches, influence yield and bioactivity. Purification techniques such as ion-exchange chromatography, gel permeation chromatography, and protein removal further refine these compounds. Optimizing extraction and purification strategies is essential to enhance the efficiency and commercial viability of green algae polysaccharides.

Fig.2 Polysaccharides extraction and purification in green algae.1

Fig.2 Polysaccharides extraction and purification in green algae.1

FAQs

Q: What do you know about polysaccharides?

A: Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates made up of long chains of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds. They are essential in biological systems, including energy storage (starch in plants, glycogen in animals) and structural support (cellulose in plants, chitin in fungi and arthropods). Their large molecular size makes them less soluble in water and more resistant to enzymatic breakdown, allowing them to provide long-term energy storage and structural integrity. In addition to their biological roles, polysaccharides have industrial and medical applications, such as in drug delivery systems, wound healing, and biodegradable materials.

Q: Why are monosaccharides not suitable for storage?

A: Monosaccharides are highly soluble in water and metabolized quickly, making them unsuitable for long-term energy storage. Their small molecular size enables them to diffuse rapidly across cell membranes, which means they can supply energy immediately rather than being prolonged storage. If cells stored energy in monosaccharide form, the high osmotic pressure would draw excessive water into the cell, causing swelling or bursting. Instead, organisms convert monosaccharides into polysaccharides like glycogen or starch, which are more compact, osmotically stable, and can be broken down when needed for energy.

Q: Do monosaccharides ferment faster than disaccharides?

A: Yes, monosaccharides generally ferment faster than disaccharides. Since monosaccharides are single sugar units, they can be directly taken up and utilized by microbes without enzymatic breakdown. In contrast, disaccharides must first be hydrolyzed into their monosaccharide components by specific enzymes before fermentation can proceed. This extra step slows the process. For example, glucose ferments more rapidly than lactose because lactose requires lactase to break it into glucose and galactose before fermentation begins. The rate of fermentation also depends on the type of microorganism and environmental conditions.

Reference

-

Li, Chen, et al. "Polysaccharides and oligosaccharides originated from green algae: structure, extraction, purification, activity and applications." Bioresources and Bioprocessing 11.1 (2024): 85. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-024-00800-5

Related Services

Resources

For Research Use Only.

Contact Us

Follow us on

Contact Us

Follow us on

Fig.1 Examples of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Fig.1 Examples of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Fig.2 Polysaccharides extraction and purification in green algae.1

Fig.2 Polysaccharides extraction and purification in green algae.1