The Viral Glycan Shield: Immune Evasion and Vaccine Design

Enveloped viruses have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade the host immune system, with the viral glycan shield representing one of the most effective strategies. By coopting the host's own glycosylation machinery, viruses coat their surface glycoproteins—such as the HIV-1 Envelope (Env), Influenza Hemagglutinin (HA), and SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S)—with a dense layer of host-derived carbohydrates. Because these glycans are produced by the host cell, they are generally recognized as "self," thereby diminishing the immunogenicity of the underlying viral proteins. However, this shield is not an impenetrable wall; it contains structural vulnerabilities, often referred to as "glycan holes," which can be targeted by broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs). At Creative Biolabs, we provide comprehensive Anti-Viral Glycan Shield Antibody Development services to assist researchers in mapping these sites, characterizing the glycan density, and developing therapeutics that can breach this defense.

The Biological Basis of the Glycan Shield

The viral glycan shield is primarily composed of N-linked glycans, although O-linked glycans also play a role in certain viruses like Ebola and Herpes Simplex Virus. During viral replication, the viral surface proteins are synthesized in the host's endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and transported through the Golgi apparatus. It is here that the host's glycosyltransferases attach oligosaccharides to specific asparagine residues (in the context of the N-X-S/T motif, where X is any amino acid except proline).

Unlike the host's endogenous proteins, which typically display a mix of high-mannose, hybrid, and complex glycans, viral proteins often possess such a high density of potential N-linked glycosylation sites (PNGs) that the enzymatic processing is sterically hindered. This results in an unusual abundance of under-processed, high-mannose glycans—specifically oligomannose types (e.g., Man5-9GlcNAc2)—on the viral surface. This distinct "mannose patch" serves as both a shield against antibodies and a potential target for lectin-based innate immune recognition.

Mechanisms of Immune Evasion

The protective function of the viral glycan shield relies on several interconnected mechanisms that collectively reduce the efficacy of the adaptive immune response.

Steric Hindrance and Epitope Masking

The most direct function of the glycan shield is steric hindrance. The bulky carbohydrate chains physically block the access of B-cell receptors and antibodies to the conserved peptide epitopes on the viral surface proteins. This phenomenon, known as epitope masking, is particularly effective at protecting the receptor-binding domains (RBDs) and fusion machinery that are critical for viral entry but are also primary targets for neutralizing antibodies. By covering these vulnerable sites with "self" glycans, the virus forces the immune system to target more variable, non-neutralizing regions or the glycans themselves, which are poorly immunogenic.

Molecular Mimicry

Since the viral glycans are structurally identical to those found on host tissues, the immune system is tolerized against them. Developing antibodies against these structures carries a risk of autoimmunity. Consequently, B cells capable of producing high-affinity antibodies against self-glycans are typically deleted or anergized during development. This mimicry creates a "hole" in the antibody repertoire that viruses exploit to persist in the host without triggering a robust neutralizing response.

Glycan Shifting and Flexibility

The viral glycan shield is not a static armor; it is dynamic. The glycans are flexible and can sweep across the protein surface, creating an effective volume of shielding that is much larger than their static mass would suggest. Furthermore, viruses rapidly evolve by shifting the positions of their glycosylation sites (PNGs). This "glycan shifting" alters the landscape of the shield, filling in previous vulnerabilities and rendering previously effective antibodies useless. This is a hallmark of HIV-1 and Influenza evolution, necessitating continuous updates to vaccine strategies.

Viral Glycan Shield Targets

HIV-1 Envelope (Env)

HIV-1 possesses one of the densest glycan shields known in nature, accounting for approximately 50% of the Env trimer's mass. This "mannose patch" effectively hides the CD4 binding site. However, the extreme density prevents complete enzymatic processing, leaving under-processed high-mannose glycans exposed. Rare, broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) like 2G12 have evolved to recognize these specific glycan clusters rather than the protein beneath, proving that the shield itself can become a target.

SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S)

The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein is also extensively glycosylated, with 22 N-linked sites per protomer. While less dense than HIV-1 Env, the SARS-CoV-2 shield plays a critical role in masking the RBD and the N-terminal domain. Recent studies have shown that the flexibility of the Spike stalk and the dynamic motion of the glycans protect the fusion machinery. However, the shield is less effective at the apex, leaving the RBD transiently exposed in the "up" conformation for receptor binding.

Influenza Hemagglutinin (HA)

Influenza HA utilizes glycosylation primarily to protect its globular head domain, which contains the receptor-binding site. The seasonal drift of Influenza A is partly driven by the acquisition and loss of glycosylation sites, which masks antigenic epitopes from pre-existing antibodies in the population. This constant remodeling of the glycan landscape is a major reason why seasonal flu vaccines must be updated annually.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

The HCV E2 envelope glycoprotein is heavily glycosylated, which is essential for proper protein folding and immune evasion. The glycans on HCV E2 function to reduce the immunogenicity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1), acting as a decoy that distracts the immune system. Neutralizing antibodies against HCV often target discontinuous epitopes that are partially shielded by these glycans, making vaccine design particularly challenging.

Ebola/Marburg Virus Glycoprotein (GP)

Filovirus glycoproteins (GP) contain a unique mucin-like domain (MLD) rich in O-linked glycans, in addition to a dense N-glycan shield. This extensive glycosylation not only masks conserved epitopes but also sterically hinders antibody access to the receptor-binding core. Our development services focus on overcoming this steric hindrance to target the fusion machinery hidden beneath.

Flavivirus Envelope (E) Protein

Flaviviruses such as Dengue, Zika, and West Nile utilize glycosylation on their Envelope (E) proteins to modulate viral assembly and immune evasion. The specific glycan structures often vary depending on whether the virus was produced in insect vectors or mammalian hosts. We analyze these host-specific glycan profiles to develop antibodies that effectively neutralize the virus across different infection stages.

Herpesvirus Glycoproteins

Herpesviruses, including CMV, EBV, and HSV, encode a vast array of surface glycoproteins (e.g., EBV gp350, CMV gB) that are heavily glycosylated to shield critical entry machinery. This glycan density often distracts the immune system into producing non-neutralizing antibodies. We assist in mapping these shields to identify exposed, conserved epitopes suitable for therapeutic targeting.

RSV Fusion (F) & Attachment (G) Proteins

The RSV Attachment (G) protein acts as a major decoy, featuring a mucin-like domain with heavy O-glycosylation that traps antibodies. Meanwhile, the Fusion (F) protein possesses specific N-glycosylation sites that modulate its stability and antigenicity. We provide development services for antibodies that can navigate the G protein shield or target glycan-modulated sites on the F protein.

Implications for Vaccine Design

Targeting Glycan Holes

The imperfect nature of the glycan shield creates "glycan holes"—regions where the protein surface is accessible due to missing or sparse glycosylation. Identifying these holes is a primary goal in rational vaccine design. By engineering immunogens that stabilize the viral protein in a conformation that exposes these holes, researchers can focus the immune response on conserved neutralizing epitopes. However, viruses can rapidly mutate to fill these holes, leading to viral escape.

Glycan-Dependent Antibodies

A new class of therapeutic antibodies, known as glycan-dependent bnAbs, has emerged. These antibodies do not just avoid the shield; they utilize it for binding. They typically have long HCDR3 loops that penetrate the glycan layer to contact the protein surface, while simultaneously interacting with the surrounding glycans to increase affinity. Incorporating defined glycan structures into vaccine immunogens is therefore crucial to elicit these sophisticated antibodies.

Our Solutions for Glycan Shield Research

Creative Biolabs offers a suite of advanced services to dissect the viral glycan shield and develop countermeasures. We combine high-resolution structural biology with immunological assays to support your vaccine and antibody discovery programs.

Anti-Viral Glycan Shield Antibody Development

We specialize in generating antibodies that target glycan-dependent epitopes. Using our proprietary phage display libraries and single B-cell sorting platforms, we isolate binders that can recognize specific glycan-protein interfaces or high-mannose clusters characteristic of viral envelopes.

Glycoarray Platforms

Our high-throughput glycoarray platforms allow for the rapid screening of antibody specificity against hundreds of viral and host glycan structures. This service is essential for determining if your candidate antibodies are cross-reactive with host tissues or specific to the viral glycan profile.

Comprehensive Glycosylation Analysis

Understanding the composition of the shield is the first step in defeating it. We offer site-specific glycosylation analysis using mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to map the glycan occupancy and heterogeneity (microheterogeneity) at each site on the viral protein.

Inquire About Glycan Shield Analysis

Published Data

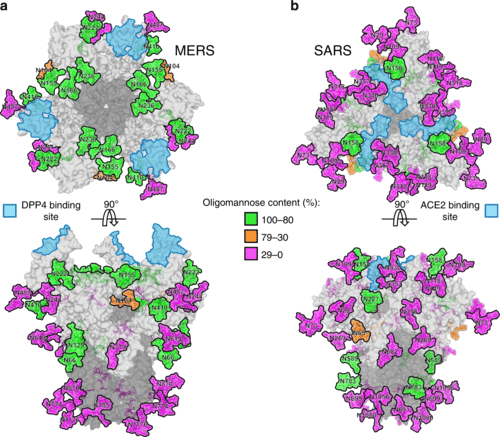

Recent structural and mass spectrometric analyses have provided a comprehensive mapping of the N-linked glycan landscape on coronavirus spike proteins, revealing critical insights into their immune evasion strategies. The study quantifies the composition of glycans across the trimeric spikes of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, distinguishing between complex, hybrid, and oligomannose structures. A key discovery is the identification of a specific high-density cluster of under-processed oligomannose glycans on the MERS-CoV spike, a feature absent in the SARS-CoV architecture. By benchmarking these profiles against other viral fusion proteins, the research demonstrates that while coronaviruses are heavily glycosylated, their glycan shields are significantly less dense than those of "evasion-strong" viruses like HIV-1. This lower density coverage suggests the shield is imperfect, containing structural vulnerabilities or "glycan holes" where the protein surface remains exposed to the host immune system. These findings elucidate why, despite extensive glycosylation, coronavirus spikes remain potent targets for neutralizing antibodies, contrasting sharply with the impenetrable defenses of other enveloped viruses. This structural characterization is instrumental for engineering immunogens that stabilize these vulnerable conformations to elicit potent therapeutic responses.

Fig.1

Structural Mapping of N-Linked Glycan Clusters on Coronavirus Spikes.1

Fig.1

Structural Mapping of N-Linked Glycan Clusters on Coronavirus Spikes.1

FAQs

What exactly is the viral glycan shield?

The viral glycan shield is a dense layer of host-derived carbohydrate molecules (glycans) that coat the surface proteins of enveloped viruses. It acts as a physical barrier that masks viral epitopes from the host's immune system, preventing antibody recognition and neutralization.

How does the glycan shield impact vaccine development?

The shield poses a major challenge by hiding conserved viral epitopes. Effective vaccines must be designed to either target the rare "holes" in this shield or elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies that can penetrate or bind to the glycans themselves.

Can antibodies be developed against the glycan shield itself?

Yes. While difficult, the body can produce broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) that recognize specific clusters of high-mannose glycans or mixed glycan-protein epitopes. We specialize in developing such antibodies for research purposes.

What is the difference between "glycan holes" and "glycan shifting"?

"Glycan holes" are specific areas on the viral surface that lack glycosylation and are vulnerable to antibodies. "Glycan shifting" is an evolutionary mechanism where the virus mutates to add or move glycosylation sites, effectively covering these holes and escaping immune pressure.

Why do viruses use N-linked glycans for shielding?

N-linked glycans are bulky and can be densely packed. Viruses exploit the host's N-glycosylation machinery because these structures are large enough to provide significant steric hindrance and are easily recognized as "self" by the host, minimizing immune activation.

Do you offer services to map glycosylation sites on viral proteins?

Yes, our Glycosylation Analysis service utilizes liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to precisely map glycosylation sites (occupancy) and characterize the glycan structures (composition) present on viral antigens.

Reference:

- Watanabe, Y., et al. "Vulnerabilities in coronavirus glycan shields despite extensive glycosylation." Nature Communications 11.1 (2020): 2688. Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16567-0