A Researcher's Guide to Blood Group Antigens: Molecules, Genetics, and Study

As specialists in biotechnology, Creative Biolabs has witnessed the evolution of the science of human biology. Few subjects are as fundamental and complex as human blood groups. When most people hear "blood type," they think of A, B, O, and a "positive" or "negative" result. This system is essential for safe blood transfusions. For the research community, this is just the beginning. Blood groups are a vast system of molecules on our cell surfaces. These molecules are the antigens. They are functional molecules involved in our immune system, genetic inheritance, and even our relationship with diseases. Our extensive work in this area, including projects focused on Anti-Blood Group Antigens Antibody Development, has given us a deep appreciation for their complexity. This guide will explore the deep science of these critical molecules.

What are Antigen and Antibody in Blood Group Systems?

To understand blood groups, we must first define two key molecules: antigens and antibodies.

- Antigens: An antigen of a blood group is a specific molecule on the surface of your red blood cells (RBCs). Your body recognizes this molecule as "self."

- Antibodies: An antibody is a protein found in your blood plasma. It is a core part of your immune system. Its job is to find and neutralize foreign substances, which are called "non-self" substances.

Explain the Antigen-Antibody Response as it Relates to Blood Groups

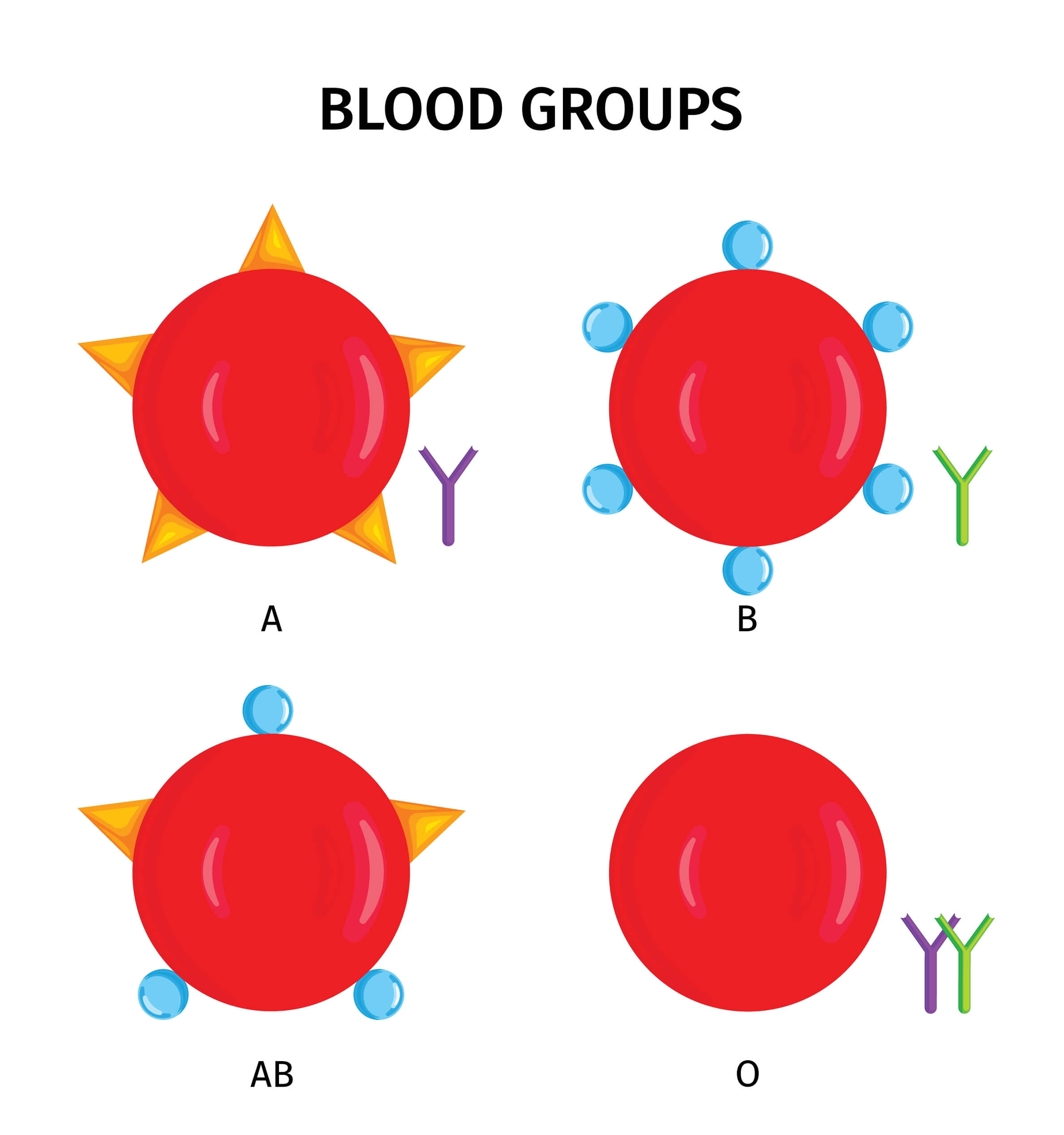

Fig.1 The ABO blood group system.

Fig.1 The ABO blood group system.

The relationship between antigen antibody in blood group systems is the basis of immune safety. Your immune system learns to recognize all the antigens that are a normal part of your body. It will attack any antigen it does not recognize as "self." You naturally produce antibodies against the major blood group antigens that you do not have. This is how it works:

- If you have Type A blood, your RBCs have A antigens. Your plasma contains Anti-B antibodies to attack B antigens.

- If you have Type B blood, your RBCs have B antigens. Your plasma contains Anti-A antibodies to attack A antigens.

- If you have Type AB blood, your RBCs have both A and B antigens. Since both are "self," your plasma has no Anti-A or Anti-B antibodies.

- If you have Type O blood, your RBCs have neither A nor B antigens. Because both A and B are foreign to your system, your plasma contains both Anti-A and Anti-B antibodies.

An incompatible blood transfusion is dangerous because the recipient's antibodies find and attack the donor's "foreign" red blood cells. This attack causes the cells to be destroyed, which is a life-threatening immune response.

Research Challenges in Studying Glycan Antigens

This complexity presents significant challenges for researchers. The study of glycan antigens, a field known as glycobiology, is notoriously challenging. Unlike proteins, which are directly coded by a single gene, glycan structures are built by a series of different enzymes. This process can result in highly diverse and varied structures, even on the same cell type. This makes them very difficult to study. Researchers often face two major hurdles:

- Characterization: How can you precisely identify a specific glycan antigen structure within a complex biological sample?

- Reagents: How do you create antibodies that can specifically recognize one subtle sugar structure and not another?

At Creative Biolabs, our teams specialize in overcoming these exact challenges. We provide the expert services necessary to advance complex glycobiology research:

Anti-Glycan Antibody Development

Developing high-specificity, high-affinity antibodies against carbohydrates is a primary bottleneck in the field. We use advanced technologies, including phage display, to develop custom anti-blood group antigens antibodies tailored to your specific glycan target. This ensures your research tools have the highest possible precision.

ABH-Glycan Arrays

Standard reagents are often not available for rare or novel blood group antigens. We provide expert custom glycan synthesis to build the exact carbohydrate structures you need for your study. We can then place these structures onto our ABH-glycan array platform for high-throughput screening of antibody binding, lectin interactions, or pathogen adherence.

The Core Blood Group Systems: ABO and Rh

Scientists have identified over 40 different blood group systems. The two most important for medicine and research are the ABO system and the Rh system.

The ABO System

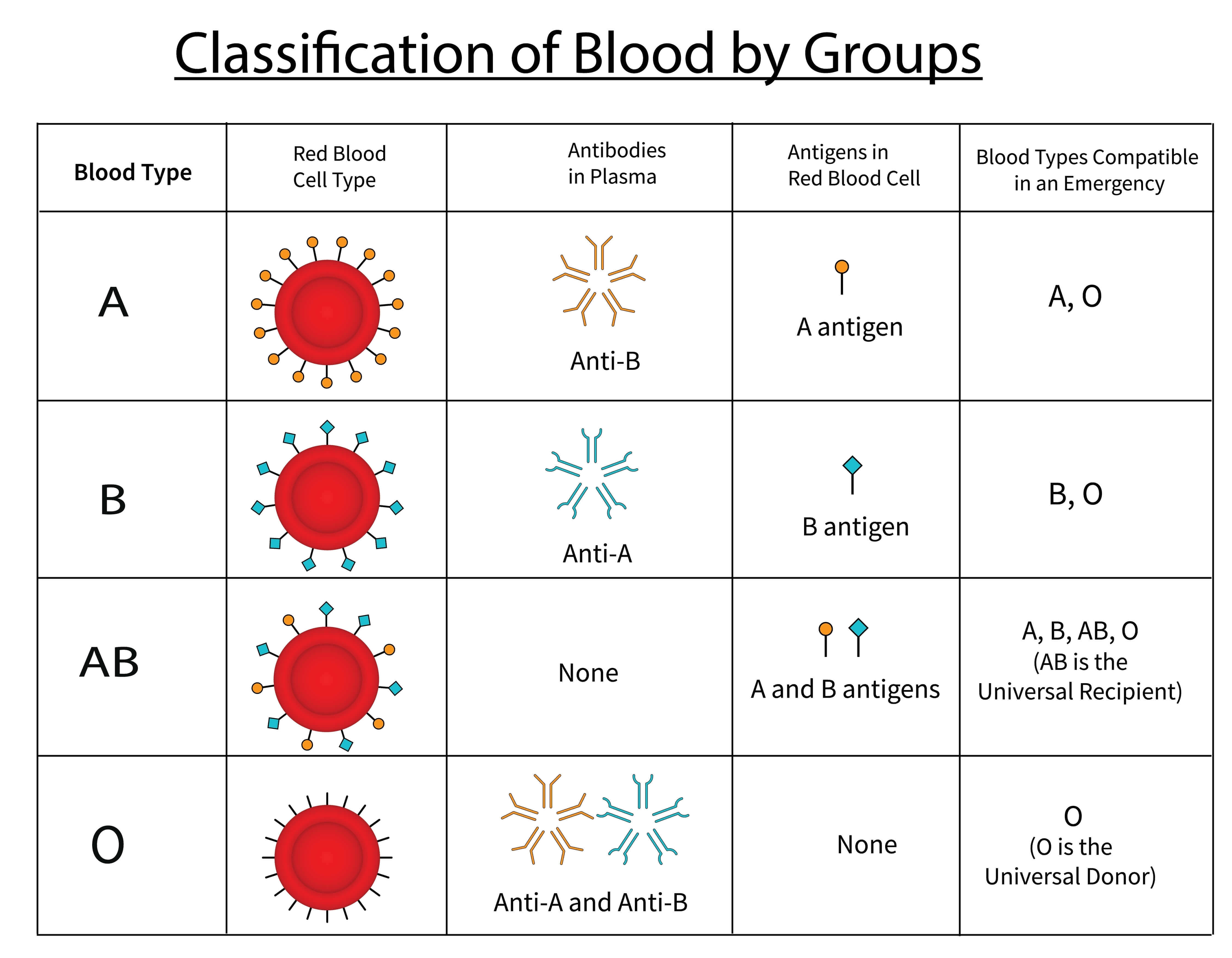

ABO antigens are complex carbohydrates, not proteins. These sugars are attached to proteins or lipids on the cell membrane. These combined structures are called glycoconjugates, which include glycoproteins and glycolipids. The ABO system is the most critical for transfusions. It classifies blood based on the presence or absence of the A and B carbohydrate antigens. A common question is, which blood group has no antigen? The answer is Blood Group O. This means Group O red blood cells lack both the primary A and B antigens. We will discuss its precursor molecule, the H antigen, later in the biochemistry section. This lack of A and B antigens is why Group O red blood cells are least likely to be attacked by a recipient's immune system. Here is a simple blood group antigen and antibody chart to summarize the ABO system.

| Blood Group | Antigens on Red Blood Cells | Antibodies in Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| A | A Antigen | Anti-B |

| B | B Antigen | Anti-A |

| AB | A and B Antigens | None |

| O | None (Has H antigen) | Anti-A and Anti-B |

The Rh System

The RhD antigen is a large protein that passes through the red blood cell membrane. The Rh system is the second most significant. It is highly complex and contains over 50 different antigens. The most important antigen in this system is the RhD antigen.

- Rh-Positive (Rh+): Your red blood cells have the RhD antigen. This antigen is a protein.

- Rh-Negative (Rh-): Your red blood cells lack the RhD antigen.

There is a key difference from the ABO system. Rh-negative people do not naturally produce Anti-D antibodies. A person must first be exposed to Rh-positive blood to become "sensitized" and begin producing these antibodies. This exposure can happen through a previous transfusion or during pregnancy. This sensitization process is the cause of Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn (HDN). If a Rh-negative mother carries a Rh-positive fetus, her immune system may create Anti-D antibodies after exposure to the fetus's blood. In a second pregnancy with another Rh-positive fetus, those antibodies can cross the placenta and attack the fetus's red blood cells. Combining the ABO and Rh systems gives us the 8 familiar blood types: A+, A-, B+, B-, AB+, AB-, O+, and O-.

The Biosynthesis of ABO Antigens

The creation of ABO antigens is a precise, two-step enzymatic process. It begins with a precursor molecule called the H antigen.

- Step 1: Making the H Antigen. An enzyme encoded by the H gene attaches a fucose sugar to a precursor chain. This new structure is the H antigen. This is the final antigen found on Group O red blood cells.

-

Step 2: Making A and B Antigens. This step is controlled by the ABO gene. This gene codes for an enzyme called a glycosyltransferase.

- The A allele is a gene variant that codes for an "A-transferase." This enzyme adds a specific sugar, N-acetylgalactosamine, to the H antigen. This creates the A antigen.

- The B allele codes for a "B-transferase." This enzyme adds a different sugar, galactose, to the H antigen. This creates the B antigen.

- The O allele codes for a non-functional enzyme. It cannot add any sugar, so the structure simply remains as the H antigen.

This pathway clearly explains why Group O individuals have both Anti-A and Anti-B antibodies. Their immune systems have never been exposed to the specific A or B sugar structures, so they view them as foreign.

The Genetics of Blood Groups

Your blood group is determined by genes inherited from your parents. These genes are located at specific sites, called loci, on your chromosomes. Different versions of a gene at the same locus are called alleles.

Blood Groups as Genetic Markers

Blood groups are inherited in a clear and predictable pattern. This quality made them one of the first and most useful tools for human geneticists. They serve as "genetic markers" to study inheritance patterns in families. This allows researchers to investigate genetic linkage. Genes that are physically close together on the same chromosome are "linked" and tend to be inherited together. By tracking how blood groups are inherited alongside other traits, scientists could determine if the gene for that trait was located near a known blood group gene. This was a foundational method for mapping human genes.

Blood Groups, Populations, and Evolution

The frequencies of blood group genes vary dramatically across different human populations. This variation provides powerful clues about human migration, genetic drift, and natural selection.

- Group A: Highest frequencies are found among Australian Aborigines and the Blackfoot Indians of Montana.

- Group B: Reaches its highest frequency in Central Asia and northern India.

- Group O: Extremely common worldwide, particularly among the indigenous peoples of Central and South America.

- Rh System: The allele for Rh-negative blood is common in European populations (about 40%) but much less common in African populations (about 20%). It is almost completely absent in East Asian populations. As a result, Rh-related HDN is extremely rare in these populations.

This evolutionary link extends beyond humans. Our closest primate relatives, such as chimpanzees, also have blood group systems that are very similar to ours. This shows the deep evolutionary roots of these cell markers.

Blood Group Antigens in Disease Research

Today, the study of blood group antigens is a rapidly expanding field. We now know these antigens play active roles in health and disease. For example, many pathogens use blood group antigens as attachment points to infect host cells. Furthermore, changes in blood group antigen expression are a well-known hallmark of some cancers. These cancer-specific glycans are known as Tumor-Associated Carbohydrate Antigens (TACAs). This research opens exciting new possibilities for therapy. But to target these TACA or pathogen-binding sites, researchers first need a high-quality, specific antibody. This is where modern research tools become essential. Creating antibodies against glycan targets is a well-known technical challenge.

Our Services for Specialized Antibody Discovery

We specialize in overcoming the challenges of carbohydrate immunology. Our foundational Anti-Blood Group Antigens Antibody Development Service is designed to create high-affinity antibodies specifically for these complex blood-related targets. Our expertise extends to highly specific and challenging areas. Many TACAs are glycolipids, which require unique approaches for antibody generation. Our Custom Anti-TACA Antibody Development Service is designed for different kinds of TACA targets. And our Anti-Glycolipid Antibody Development Service is tailored for these lipid-conjugated glycan targets. Furthermore, we have deep experience in cancer research, including Anti-MUC1 Glycan Antibody Development Service to generate antibodies that specifically recognize the aberrant, cancer-associated glycoforms of MUC1. Using advanced platforms, our scientific team can generate and screen novel monoclonal antibodies for your precise target. We deliver the reliable tools you need to move your project from a promising idea to a functional study.

The antigen of a blood group is far more than a simple typing marker. It is a complex glycan or protein, a product of a precise enzymatic pathway, and a key molecule in human health, genetics, and disease. Whether you are characterizing a novel antigen, developing a specific anti-glycan antibody, or validating a new therapeutic, Creative Biolabs is ready to support your research. Are you facing a challenge with a specific glycan target? Contact our expert team today to discuss how we can accelerate your project.

Supports

- Understanding Glycosylation

- Glycosylation Influences Blood Type

- Guide to Blood Group Antigens

- Comparing sLeA and sLeX Roles in Cancer

- CA19-9 as a Pancreatic Cancer Biomarker

- Lewis Antigen System Overview

- TACA-Targeted ADCs, CAR-Ts, and RICs