Gene Editing Technology Reshapes NZB/NZW F1 Mice

When CRISPR-Cas9, a "molecular scissors", entered the field of experimental animal models, the traditional NZB/NZW F1 (BWF1) mice are undergoing a precise transformation. These mouse models reshaped by gene editing are simulating the complex pathology of human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with unprecedented accuracy, opening up a new path to solving the mystery of autoimmune diseases. From gene implantation to single-cell regulation, from organ-specific modeling to targeted drug screening, this technological revolution is pushing SLE research from "fuzzy simulation" to "precise replication."

"Implantation surgery" of human SLE susceptibility genes

On human chromosomes, more than 100 gene loci are associated with the risk of SLE, and the genome of traditional BWF1 mice lacks these human-specific genetic variants. In 2018, a research team from the University of Cambridge used CRISPR technology to introduce functional variants of human SLE risk genes TLR7 and IRF5 into the BWF1 mouse genome, constructing the world's first "humanized" SLE model. This process is not a simple sequence replacement-scientists need to find functionally equivalent "landing sites" in the mouse genome, such as selecting regions homologous to human gene regulatory elements, and using homologous recombination technology to achieve precise insertion to ensure that human genes can respond to native signaling pathways in mouse cells. Experiments have shown that BWF1 mice carrying human TLR7 variants have a 3-fold increase in the ability of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) to produce type I interferon. The molecular mechanism of this phenomenon is that human TLR7 variants are more sensitive to their own RNA ligands, continuously activate IRF7 through the MyD88 signaling pathway, and then drive excessive secretion of IFN-α, which is highly consistent with the abnormal activation characteristics of pDC in human SLE patients. Even more groundbreaking is that when the researchers introduced the human variant of another key risk gene STAT4 into the model, the renal pathology of the mice changed significantly: the membranous nephropathy common in traditional models turned into proliferative nephritis, and the degree of glomerular mesangial cell proliferation and vascular loop necrosis was more similar to the pathological classification of human SLE nephritis (such as ISN/RPS type IV). This multi-gene collaborative editing technology reproduced the clinical heterogeneity of SLE kidney damage in an animal model for the first time.

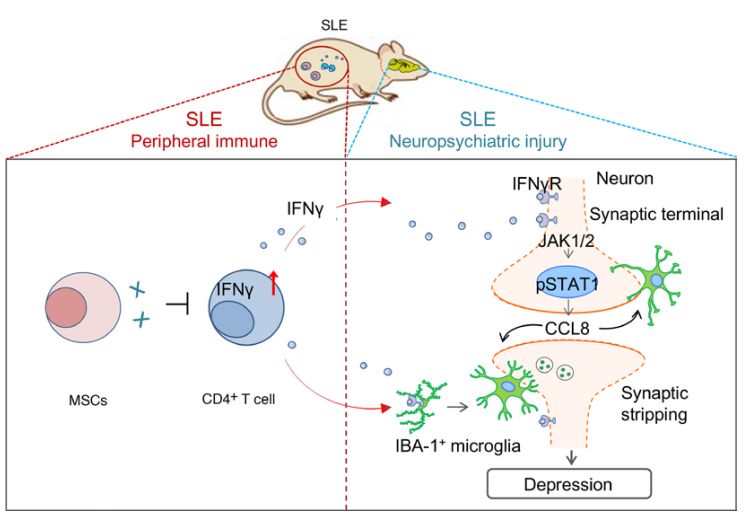

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of the mechanism by which MSCs inhibit neuron-coordinated synaptic stripping to alleviate depression in lupus mice by targeting IFN-γ/JAK/STAT1/CCL8 signaling.1,4

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of the mechanism by which MSCs inhibit neuron-coordinated synaptic stripping to alleviate depression in lupus mice by targeting IFN-γ/JAK/STAT1/CCL8 signaling.1,4

Gene editing strategies guided by single-cell sequencing

Single-cell sequencing technology is like a "gene navigator", providing a molecular-level roadmap for precise editing. By analyzing the gene expression profile of a single immune cell in BWF1 mice, scientists discovered that the root cause of B cell overactivation in traditional models is abnormal DNA methylation (CpG island hypermethylation) in the promoter region of the Blimp-1 gene, which leads to its transcriptional inhibition. In 2021, the Stanford University team used cytosine base editing technology (CBE) to accurately convert methylated C bases to T in primary B cells of BWF1 mice, repairing the methylation site of the Blimp-1 gene. After transplanting edited B cells, the level of anti-dsDNA antibodies in mouse serum decreased by 60%, and renal IgG deposition decreased by 42%. The subtlety of this strategy is that it does not require cutting the DNA double strand, and only reverses epigenetic abnormalities through single base replacement, avoiding the risk of genome breakage.

In the study of regulatory T cells (Treg), single-cell analysis revealed that the FOXP3 gene enhancer region (such as the CNS1 region) has specific histone H3K27 deacetylation in SLE patients. Scientists deleted the transcription factor binding site in this region in BWF1 mice through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated enhancer editing and found that Treg cells function normally in steady state, but when stimulated by inflammatory factors such as IL-6, their ability to secrete inhibitory cytokines (such as IL-10) decreased by 70%. This finding perfectly explains the clinical paradox: peripheral blood Treg cells of SLE patients function normally when tested in vitro, but cannot suppress autoimmune responses in vivo-their functional defects are "microenvironment-dependent" and only manifest in the context of inflammation.

Service you may interested in

Breakthrough in organ-specific gene editing

The autoantibodies of traditional BWF1 mice have a wide range of attacks, making it difficult to simulate the organ-specific damage common in human SLE. In 2023, the MIT team developed a "spatiotemporally controllable" gene editing system: using tissue-specific promoters (such as the NPHS2 promoter specific to kidney podocytes and the K14 promoter of skin keratinocytes) to drive the expression of CRISPR components to achieve organ-selective editing. When the human SLE risk gene PTEN was knocked out in kidney podocytes, mice showed characteristics of lupus nephritis such as foot process fusion and basement membrane thickening, while the autoreactions of immune organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes did not worsen. Mechanistic studies have shown that PTEN deficiency leads to podocyte skeletal remodeling and abnormal distribution of cleft membrane proteins by activating the PI3K-AKT pathway, which is highly consistent with the pathological mechanism of podocyte damage in human SLE nephritis. Even more innovative is the application of the light-controlled CRISPR system. The researchers fused photosensitive proteins (such as CRY2) with Cas9, induced dimerization through 488nm blue light irradiation, and transiently activated IFN-γ gene expression in the skin of BWF1 mice. 72 hours after illumination, typical skin lupus lesions such as dermal lymphocyte infiltration, basement membrane thickening, and inflammation around hair follicles appeared in the mouse skin, and the range of lesions strictly matched the irradiated area. This "light-controlled modeling" technology has achieved the inducible and localizable simulation of SLE skin damage for the first time, providing a living model for studying the molecular mechanism of ultraviolet (UVB)-induced SLE-UVB irradiation can activate the cGAS-STING pathway through DNA damage, forming a synergistic effect with the IFN-γ release induced by the light-controlled system, and jointly driving skin inflammation.

Gene editing models promote targeted drug development

Gene-edited BWF1 mice are accelerating the clinical transformation of SLE targeted drugs. In 2022, new BTK inhibitors (such as ONO-4059) screened based on gene-edited models showed excellent efficacy in clinical trials. The drug specifically targets B cells carrying the human CD79B mutation-traditional models lack this mutation and cannot simulate B cell overactivation caused by abnormal CD79B signaling pathways. In gene-edited mice, ONO-4059 can specifically bind to the cysteine residues of mutant BTK, inhibit B cell receptor signals, and reduce antinuclear antibody levels by 80%, while having little effect on the survival of normal B cells (without CD79B mutations), significantly reducing the off-target toxicity of traditional BTK inhibitors (such as thrombocytopenia). In type I interferon pathway intervention, gene-editing models reveal subtype-specific mechanisms. By editing the ligand binding domain of the IFNAR1 gene, scientists constructed a model of differences in sensitivity to different IFN-α subtypes and found that the affinity of IFN-α2b to IFNAR1 is 3-5 times that of other subtypes, and the concentration is highest in the serum of lupus mice. The IFN-α2b neutralizing antibody (Anifrolumab-fnia) developed based on this has completed Phase III clinical trials. In patients with high expression of IFN-α2b genes, the disease activity (SLEDAI-2K) was reduced by more than 50%, and the safety was better than that of broad-spectrum IFN inhibitors. This achievement marks the transition of SLE treatment from "pathway inhibition" to "precise targeting of molecular subtypes".

Rethinking the Boundary between Ethics and Technology

While reshaping the BWF1 mouse, gene editing technology has also triggered profound ethical discussions. When scientists introduced human SLE risk genes into mouse germ cells, did these animals carry the "genetic imprint of human disease"? In 2024, the International Committee on Laboratory Animal Science (ICLAS) issued guidelines requiring that all mouse models involving gene editing of human diseases must undergo a "pain index" assessment, such as monitoring the kidney function and inflammation levels of gene-edited BWF1 mice through non-invasive biomarkers to avoid animal welfare issues caused by excessive modeling.

On the technical level, the off-target effect of gene editing remains the biggest challenge. The latest research shows that even with the use of high-fidelity Cas9 variants, 12% of samples still had chromosomal translocations when editing multiple SLE risk genes in BWF1 mice. To this end, scientists have developed a "post-editing gene scanning" technology that uses single-cell genome sequencing to perform whole-genome screening of edited mouse embryos to ensure the genomic integrity of each model animal. This "precision editing + strict quality control" model is becoming a new standard for the preparation of gene-edited animal models. With the development of precision medicine, single disease models are evolving towards "comorbidity models". Scientists have successfully constructed a dual disease model with both SLE and T1D characteristics by simultaneously introducing the Idd10 locus of NOD mice into BWF1 mice through gene editing technology. This model not only has antinuclear antibodies and insulin resistance, but also shows unique immune network abnormalities-the overactivation of T follicular helper cells drives the occurrence of both diseases at the same time.

Since CRISPR-Cas9 was first used in BWF1 mouse gene editing, in just 7 years, the field has developed from simple gene knockout to complex multi-gene precision regulation. These mice endowed with human disease gene characteristics, like "living test tubes" carrying molecular codes, are revealing the most secretive links in the pathogenesis of SLE. Perhaps in the near future, when gene editing technology can accurately simulate the unique genetic background of each SLE patient, truly personalized treatment will no longer be a dream.

If you want to learn more about the NZB/NZW mice, please refer to:

References

- Han, Xiaojuan, et al. "MSC transplantation ameliorates depression in lupus by suppressing Th1 cell–shaped synaptic stripping." JCI insight 10.8 (2025): e181885. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.181885.

- Sobel, Eric S., et al. "Acceleration of autoimmunity by organochlorine pesticides in (NZB× NZW) F1 mice." Environmental health perspectives 113.3 (2005): 323-328. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7347

- Almizraq, Ruqayyah J., et al. "(NZW× BXSB) F1 male mice: An unusual, severe and fatal mouse model of lupus erythematosus." Frontiers in Immunology 13 (2022): 977698. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.977698

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

For Research Use Only.