Type 1 Diabetes in NOD Mice: Model Characteristics & Research Applications

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) affects over 1.25 million individuals in the United States alone, with a global prevalence that continues to rise, particularly among children and adolescents. This autoimmune disorder stems from the immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic β-cells, a process driven by genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immune dysregulation. Animal models serve as indispensable tools in T1D research, bridging basic science discoveries with clinical translation. The Non-Obese Diabetic (NOD) mouse, in particular, has revolutionized the field since its identification, offering a spontaneous, genetically tractable model that mirrors human T1D pathogenesis with remarkable fidelity.

Key Characteristics of the NOD Mouse Model

Biological Features

NOD mice exhibit a non-obese phenotype with striking sex-specific disease incidence: up to 90–100% of females develop T1D by 30 weeks, compared to 40–60% of males. Disease progression follows a defined timeline: insulitis (inflammation of islets) appears at 4–5 weeks, β-cell loss intensifies by 12 weeks, and clinical symptoms like hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis manifest between 12–30 weeks. This natural progression mirrors human T1D, making NOD mice invaluable for longitudinal studies.

Genetic Susceptibility

The NOD genome harbors a unique MHC haplotype (H2g7) and over 30 insulin-dependent diabetes (Idd) loci, such as Idd1, Idd3, and Idd5.1, which collectively drive autoimmunity. Notably, NOD mice share genetic markers with human T1D, including variants in PTPN22 (involved in T-cell regulation) and INS (the insulin gene), enhancing their translational relevance.

Historical Development of the NOD Strain

The NOD lineage traces back to the 1970s, when researchers at Shionogi Pharmaceutical in Japan observed spontaneous cataracts in an inbred ICR mouse colony. Subsequent breeding revealed that some offspring developed hyperglycemia, prompting focused selection for diabetic phenotypes. After 20 generations of brother-sister mating, the NOD strain was established as an inbred line by 1980, with consistent T1D incidence and reproducible immunological traits.

Landmark studies in the 1980s and 1990s solidified its utility: researchers demonstrated that NOD mice could transfer diabetes via splenocytes, pinpointed the role of MHC class II in disease susceptibility, and characterized the sequential immune cell infiltration into islets. The strain's global distribution through academic and commercial repositories (e.g., Jackson Laboratory) accelerated collaborative research, making NOD mice the most widely used model for T1D worldwide.

Service you may interested in

Autoimmune Mechanisms in NOD Mice

Immune Dysregulation

The pathogenesis of T1D in NOD mice is driven by a breakdown in central and peripheral immune tolerance. In the thymus, deficient negative selection of autoreactive T cells allows β-cell-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to enter the periphery. Peripheral tolerance failure is evident in reduced numbers and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which exhibit impaired suppressive capacity in NOD mice due to defects in Foxp3 expression and metabolic fitness.

B cells play a dual role: they not only produce autoantibodies (e.g., anti-insulin, anti-GAD65) but also act as antigen-presenting cells, priming T cells in lymph nodes. Follicular helper T cells (Tfh) in NOD mice show hyperactivity, promoting aberrant B-cell differentiation and germinal center formation, a process that correlates with autoantibody titers and disease progression.

Cytokine Pathways

The inflammatory milieu within NOD islets is dominated by Th1-type cytokines. IFN-γ, secreted by infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, upregulates MHC class II and inflammatory genes in β-cells, rendering them more susceptible to immune recognition. IL-6, produced by macrophages and T cells, activates the STAT3 pathway in β-cells, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Additionally, TNF-α and IL-1β contribute to islet inflammation by recruiting immune cells and disrupting β-cell function, highlighting the complex cytokine network driving disease.

Research Applications of NOD Mice

Drug Development

NOD mice have been pivotal in preclinical testing of immunomodulatory therapies. For example, anti-CD3 antibodies, which transiently deplete and rebalance T-cell populations, showed efficacy in preserving β-cell function in NOD mice, leading to clinical trials in newly diagnosed T1D patients. Similarly, agonists of CTLA-4, a negative regulator of T-cell activation, have been evaluated for their ability to enhance Treg function and dampen autoimmunity.

β-cell protective strategies, such as antioxidants and anti-apoptotic agents, have also been validated in NOD mice. Studies exploring the role of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs in promoting β-cell survival and proliferation have leveraged NOD mice to demonstrate efficacy prior to human trials.

Complication Studies

Beyond β-cell destruction, NOD mice develop microvascular complications resembling human T1D. Diabetic retinopathy in NOD mice is characterized by retinal vascular permeability, capillary dropout, and neovascularization, mirroring early stages of human disease. This has enabled investigations into angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) and anti-inflammatory strategies to prevent vision loss.

NOD-SCID/NSG mice, which lack mature T, B, and natural killer cells, serve as hosts for human immune system reconstitution (huNOD mice). These humanized models allow researchers to study T1D pathogenesis with human immune cells and have been used to evaluate the efficacy of human-specific biologics, such as anti-IL-2 receptor antibodies.

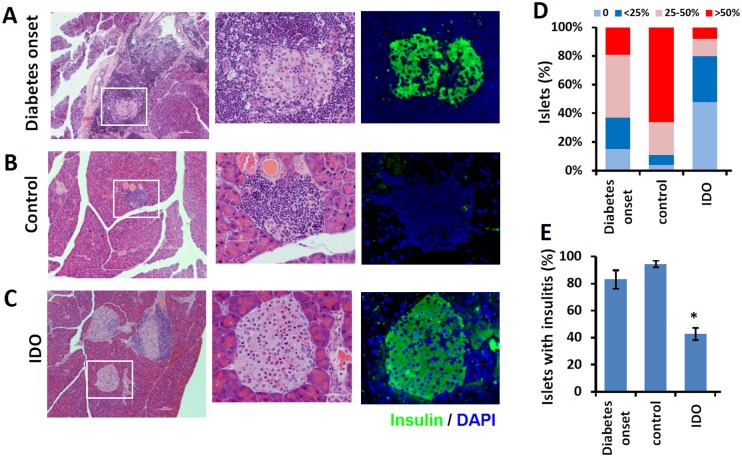

Fig.1 Cell therapy's impact on pancreatic histology in NOD mice.1,2

Fig.1 Cell therapy's impact on pancreatic histology in NOD mice.1,2

Comparative Analysis with Other T1D Models

NOD vs. BB Rats

The Bio-Breeding (BB) rat, another spontaneous T1D model, shares similarities with NOD mice, including MHC-linked susceptibility and T-cell-mediated pathogenesis. However, BB rats exhibit a higher incidence of complete immune deficiency (due to thymic aplasia in some substrains), making them more prone to infections. In contrast, NOD mice retain a functional innate immune system, allowing study of host-pathogen interactions in the context of autoimmunity. Genetic manipulation is also more straightforward in mice, with a broader range of transgenic and knockout tools available.

Strengths Over Induced Models

Chemically induced models (e.g., streptozotocin, STZ) and transgenic models (e.g., RIP-LCMV) offer simplicity but lack the complex immune priming of spontaneous T1D. STZ-induced diabetes, for instance, relies on β-cell cytotoxicity rather than autoimmune destruction, failing to recapitulate the preclinical autoantibody phase seen in humans. Transgenic models expressing viral antigens in β-cells depend on immune responses to foreign antigens, which may not mirror endogenous autoimmunity. NOD mice, by contrast, emulate the gradual loss of tolerance and immune cell infiltration characteristic of human T1D.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their utility, NOD mice exhibit notable species-specific differences from humans. The female-biased incidence contrasts with human T1D, which shows a slight male predominance in children. Additionally, insulitis in NOD mice is primarily lymphocytic, whereas human islets often feature more diverse immune cell populations, including neutrophils and eosinophils.

Immune reactions to experimental tools pose another challenge. NOD mice may mount adaptive immune responses to xenogeneic cells or fluorescent markers (e.g., GFP), limiting long-term tracking of immune cell behavior. Translation to humans is further hindered by differences in immune cell subsets—for example, NOD mice have lower numbers of circulating memory T cells compared to humans, which may affect therapy efficacy.

If you want to learn more about the diabetic animal models, please refer to:

Future Directions and Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of NOD Mice

Advances in CRISPR-Cas9 technology enable precise editing of T1D-linked genes (e.g., RNLS, PTPN22) in NOD mice, allowing researchers to model human genetic variants. HLA-transgenic NOD mice, which express human major histocompatibility complex molecules, hold promise for mimicking human immune responses more accurately, reducing translational gaps.

While organoids and single-cell sequencing offer new perspectives, NOD mice will continue to serve as a cornerstone in T1D research. Their legacy lies in decades of insights into autoimmune pathways, genetic determinants, and therapeutic targets. Balancing their strengths with limitations—such as combining NOD models with humanized systems or organoid co-cultures—will drive future discoveries.

The NOD mouse model has been indispensable in unraveling the complexities of T1D, from immune dysregulation to genetic susceptibility. As technology evolves, its integration with cutting-edge approaches will sustain its relevance, ensuring it remains a vital tool for advancing mechanistic understanding and developing novel therapies. Despite translational challenges, the NOD mouse's unique ability to recapitulate human T1D biology cements its role in shaping the future of diabetes research.

References

- Jalili, Reza B., et al. "Fibroblast cell-based therapy for experimental autoimmune diabetes." PLoS One 11.1 (2016): e0146970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146970

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

For Research Use Only.