Streptozotocin induced Diabetes: Protocols & Experimental Insights

Introduction to Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes

Streptozotocin (STZ), a naturally occurring nitrosourea compound, has been a cornerstone in experimental diabetes research for decades. Discovered in the 1960s from streptomyces achromogenes, STZ's diabetogenic properties arise from its unique chemical structure, combining a methylnitrosourea moiety with a glucose moiety. This structural feature enables selective targeting of pancreatic β-cells, making it invaluable for modeling both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in animal models.

Compared to alternative diabetogenic agents like alloxan, STZ offers distinct advantages: greater chemical stability, reduced systemic toxicity, and enhanced β-cell specificity. These attributes have solidified its role in preclinical research, allowing scientists to replicate key pathophysiological aspects of human diabetes with high reproducibility.

Mechanism of STZ Action

The cytotoxic effect of STZ on β-cells is initiated by its uptake via GLUT2 transporters, which are highly expressed in these cells. Once internalized, the methylnitrosourea component undergoes decomposition, leading to DNA alkylation and fragmentation. This process triggers a cascade of events, including the depletion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), critical cofactors for cellular energy metabolism.

Concurrently, STZ induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), promoting oxidative stress. The combination of DNA damage and ROS production activates the poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) pathway, further exacerbating NAD+ depletion. This metabolic crisis culminates in β-cell necrosis through mechanisms involving nitric oxide toxicity and intracellular calcium overload, ultimately leading to insulin deficiency.

Protocol Development for STZ Models

Animal Selection Criteria

Species and strain specificity significantly influence STZ model efficacy. Rats generally exhibit higher sensitivity to STZ than mice. For T1D modeling, male Sprague-Dawley (SD) or Wistar rats (220–240 g) are commonly used, while C57BL/6 mice are preferred for genetic studies. Strain variations in mice, such as KM mice requiring higher doses (80–120 mg/kg), highlight the need for careful strain validation.

Pre-injection Preparation

Fasting animals for 12–20 hours prior to STZ administration enhances β-cell vulnerability by increasing GLUT2 expression. STZ must be reconstituted in cold citrate buffer (pH 4.5) immediately before use to maintain stability, as alkaline conditions rapidly degrade the compound.

Dosing Regimens

- Type 1 Diabetes: A single high-dose protocol is standard: 50–65 mg/kg intraperitoneally (IP) in rats or 120–150 mg/kg in mice. For example, fasting SD rats injected IP with 60 mg/kg STZ typically develop sustained hyperglycemia (blood glucose ≥16.7 mmol/L) within 72 hours. Alternatively, multiple low-dose protocols (e.g., 40 mg/kg daily for 5 days) can induce a more gradual β-cell destruction, better mimicking the progressive autoimmune process in human T1D. This approach reduces acute toxicity but requires longer monitoring periods.

- Type 2 Diabetes: T2D models employ low-dose STZ (25–45 mg/kg) combined with a high-fat diet (HFD) to induce insulin resistance and partial β-cell dysfunction. A common protocol involves pre-treating HFD-fed rats with nicotinamide (60 mg/kg), a NAD+ precursor, to protect residual β-cells and promote insulin resistance. Following nicotinamide, STZ (65 mg/kg) is administered to induce oxidative stress and β-cell impairment. This combination recapitulates the dual pathology of human T2D: insulin resistance from HFD and β-cell dysfunction from STZ.

Service you may interested in

Key Differences Between T1D and T2D Models

Pathophysiological Outcomes

T1D models feature severe, rapid β-cell destruction (up to 80–90% loss within days) and absolute insulin deficiency, closely mimicking the autoimmune nature of human T1D—though without the immune-mediated component. In contrast, T2D models combine partial β-cell dysfunction (30–50% loss) with HFD-induced insulin resistance, reflecting the metabolic syndrome underlying human T2D. The latter often shows compensatory β-cell hyperplasia initially, followed by gradual failure, mirroring the clinical progression of T2D.

Dosing and Validation

T1D validation requires sustained hyperglycemia (>11.1 mmol/L) for at least two consecutive days, confirmed by tail vein blood glucose measurements. Insulin or C-peptide levels typically drop to <50% of baseline. T2D models prioritize insulin resistance metrics, such as the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and glucose tolerance tests (GTT). HOMA-IR values >2.5 indicate significant insulin resistance, while impaired glucose tolerance (2-hour post-glucose glucose >11.1 mmol/L) confirms metabolic dysfunction.

Species-Specific Considerations

Rats demonstrate higher STZ sensitivity: SD rats require 55–65 mg/kg for T1D, whereas C57BL/6 mice need lower doses (30–40 mg/kg). KM mice, however, may require 80–120 mg/kg due to genetic variations in drug metabolism enzymes, such as cytochrome P450 systems. These differences highlight the need for strain-specific dose optimization.

Mortality management is critical; high STZ doses can cause acute renal toxicity, manifesting as proteinuria and elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Dose titration is essential to balance diabetogenic efficacy with survival: in rats, exceeding 70 mg/kg may increase mortality to >30%, while in mice, doses >150 mg/kg pose similar risks. Hydration support (e.g., oral glucose solutions) and frequent glucose monitoring during the first 48 hours can mitigate hypoglycemic crises and renal stress.

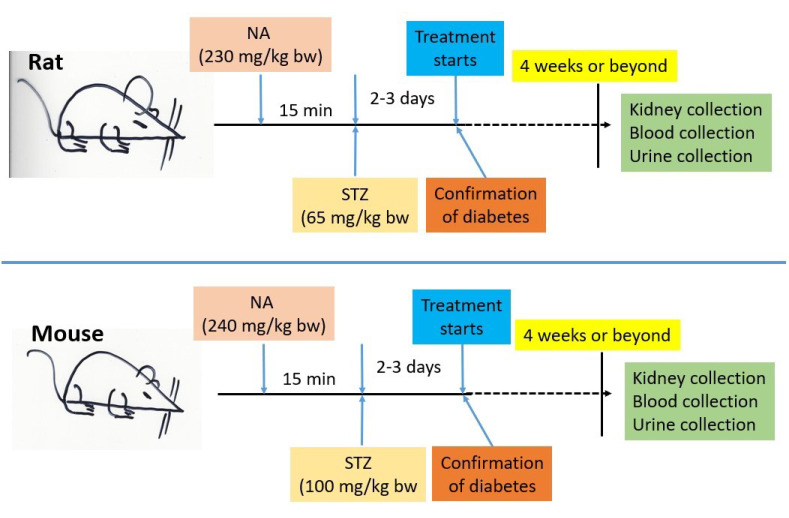

Fig.1 Inducing non-obese type 2 diabetes in animals: nicotinamide & streptozotocin protocols.1,2

Fig.1 Inducing non-obese type 2 diabetes in animals: nicotinamide & streptozotocin protocols.1,2

Model Validation and Key Metrics

Critical Biomarkers

Blood glucose monitoring follows a characteristic timeline: transient hyperglycemia within 24 hours, followed by a hypoglycemic phase (24–48 hours) due to residual insulin release, and sustained hyperglycemia by day 3–7. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices can provide real-time data, enhancing accuracy.

Insulin/C-peptide assays and oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) confirm β-cell function. In T1D models, fasting insulin levels often drop below 0.5 ng/mL, while T2D models show initial hyperinsulinemia (≥5 ng/mL) followed by blunted post-glucose insulin secretion. Histopathological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining reveals β-cell necrosis, islet inflammation, and fibrosis. Immunostaining for insulin (β-cells) and glucagon (α-cells) quantifies islet cell composition, while TUNEL assays detect apoptotic cells.

Secondary Indicators

Clinical signs such as polydipsia (water intake >50 mL/24 h in rats), polyphagia (food intake >20 g/24 h), and weight loss (>10% baseline) complement biochemical markers. Urine glucose testing (using dipsticks) and ketone body measurement (e.g., acetoacetate) can confirm diabetic ketoacidosis in severe T1D models.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Model Failure

Inadequate dosing, fasting errors, or genetic variability can lead to inconsistent results. For example, delayed fasting (e.g., <12 hours) reduces GLUT2-mediated STZ uptake, while older animals may exhibit reduced β-cell sensitivity. Solutions include repeating low-dose STZ injections (10–20 mg/kg) 7–10 days after initial dosing to target remaining β-cells or restarting the induction protocol with optimized parameters (e.g., stricter fasting or strain verification).

Mortality Risks

Acute renal toxicity, often linked to severe hyperglycemia-induced osmotic diuresis, can be mitigated by fluid resuscitation (subcutaneous saline, 10 mL/kg twice daily) and frequent glucose monitoring. Prophylactic antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin) may reduce infection risks in immunocompromised models. Additionally, avoiding overcrowding and maintaining controlled housing conditions (temperature: 22±2°C, humidity: 50±10%) minimizes stress-induced variations in model outcomes.

Recent Advances in STZ Models

Innovative approaches leverage multi-omics technologies to dissect β-cell heterogeneity and disease progression. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has identified distinct β-cell subpopulations with varying STZ sensitivity, revealing that proliferative β-cells are more susceptible to DNA damage. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have also uncovered novel pathways involved in STZ-induced necrosis, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Hybrid models combining HFD with low-dose STZ better recapitulate human T2D comorbidities, including nephropathy, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular dysfunction. For example, HFD-STZ mice develop albuminuria and glomerular hypertrophy within 12 weeks, mirroring human diabetic kidney disease. These models have expanded STZ's utility in drug screening for β-cell regeneration (e.g., glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists) and complication prevention (e.g., renin-angiotensin system inhibitors).

Conclusion and Future Directions

STZ-induced diabetes models remain indispensable for their speed, reproducibility, and adaptability to diverse research objectives. While their artificially induced nature differs from natural disease progression, ongoing refinements—such as personalized dosing algorithms and integration with gene-editing tools like CRISPR—hold promise for enhancing translational relevance. Future research will likely focus on combining STZ models with humanized tissues or organoids to bridge the gap between preclinical and clinical diabetes research.

If you want to learn more about the diabetic animal models, please refer to:

If you require the development of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes animal research models, we invite you to connect with us. Our team of seasoned experts possesses extensive years of experience in establishing diabetic animal models, specializing in the precise induction and validation of STZ-induced diabetic models. Whether for preclinical drug evaluation, pathophysiological studies, or therapeutic strategy development, Creative Biolabs' expertise ensures the creation of reliable, reproducible models tailored to your research objectives. Leverage our proven track record in model development to accelerate your scientific inquiry. Contact us today to discuss how our experienced team can design the ideal STZ-induced diabetes model to meet your specific research needs.

References

- Yan, Liang-Jun. "The nicotinamide/streptozotocin rodent model of type 2 diabetes: renal pathophysiology and redox imbalance features." Biomolecules 12.9 (2022): 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12091225

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

For Research Use Only.